When you talk about the subjects of Robert Caro’s magisterial, Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies–Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson–you have to look at them from two perspectives.

Before Caro, or B.C., they were viewed as great men whose legacy was marred by their personal flaws. This conventional wisdom is true as far as it goes, but it’s been told so often, and in such familiar ways, that it begins to take on a cartoonish quality. I remember the celebrations of presidents at one of the Democratic conventions describing Johnson as having a heart “as big as Texas.” That’s how you described Johnson: Like other successful politicians, only bigger.

Before Caro, or B.C., they were viewed as great men whose legacy was marred by their personal flaws. This conventional wisdom is true as far as it goes, but it’s been told so often, and in such familiar ways, that it begins to take on a cartoonish quality. I remember the celebrations of presidents at one of the Democratic conventions describing Johnson as having a heart “as big as Texas.” That’s how you described Johnson: Like other successful politicians, only bigger.

Except that neither Moses or Johnson was anything like the complex, Shakespearean figures that Caro has revealed in his works. After Caro, these two figures–and dozens of other supporting characters, like Moses’s mentors Al Smith and Belle Moskowitz, or LBJ’s mentor Sam Rayburn, to take a few examples–are pulsing with energy. Just as important, these works are also pulsing with whole new ways of looking at the world.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is about a good a definition of genius that you’ll ever find.

How does he do it? The simple, and true, answer is that he researches the hell out of his subjects. Fans complain that Caro is taking too long with the fifth volume of The Years of Lyndon Johnson, covering his five-plus years in the White House. But as Caro explains, there is no other way:

While I am aware that there is no Truth, no objective truth, no single truth, no truth simple or unsimple, either; no verity, eternal or otherwise; no Truth about anything, there are Facts, objective facts, discernible and verifiable. And finding facts–through reading documents or through interviewing and re-interviewing–can’t be rushed; it takes time. Truth takes time.

Researching the hell out of his subjects is just one of the many lessons for writers in Caro’s new book Working: Researching, Interviewing, Writing (Knopf, April 9). Caro’s brief work–and, by the way, this is the first and last time the words “Caro” and “brief” will ever appear in the same sentence–offers a master course in the art and craft of writing.

In this little book, Caro shows how and why he picked his subjects, how to find the throughline and plot the story’s arc, how to conduct archival research and interview subjects, how to write great scenes, explain complex processes, how to write with style, and much more. Here are a few highlights:

Subjects

Subjects

The British historian Arnold Toynbee once said that history is just “one damn thing after another.” Clever line, but untrue. History is a way of revealing something about the human condition. A great work of history, then, aspires not just to tell a story–about a person or place, event or period–but reveal some truth about life. The purpose of Caro’s works is to understand power.

“From the very start I thought of writing biographies as a means of illuminating the times of the man I was writing about and the great forces that molded those times – particularly the force that is political power. Why? political power? Because political power shapes all of our lives. It shapes your life in little ways that you might not even think about.”

To achieve this requires much more than writing one damn thing after another. For Caro, biography must serve as a “vessel for something even more significant: examination of the essential nature—the most fundamental realities—of political power.” And what should serve as the vessel? For Caro, it was a subject “who had done something no one else had done before” and then figure out how he did it.

For another author, biography could be the vessel to explore art or love or psychology or sports. Whatever its purpose, it cannot be just a recounting of what happened.

Research

Discipline–exploring every possible angle, looking at every piece of evidence, chasing down every lead–is the key to all great nonfiction narrative. Caro learned that lesson early, as a reporter for Newsday. He once got a call about the corruption behind the disposition of an Air Force base on Long Island. Come see these documents, a source told him. And so he did. He spent all night reading the documents and taking copious notes.

His editor, who had previously ignored him, was impressed. From now on, he said, you will be an investigative reporter. “Just remember,” he said. “Turn every page. Never assume anything. Turn every goddamn page.”

He took that advice to heart, making it his mission to dig deeper than anyone ever dug before on his biographies of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson.But when he got to the Johnson Presidential Library in Austin, he knew he had to be more selective. The library held 40,000 boxes containing 32 million pages.

No one of historical importance wants his career to be investigated without fear or favor. Historic figures spend their lifetimes creating a mythology. They do not want it dismantled.

Therefore, the biographer must start far away from the subject. When Caro started work on his Moses book, he refused interviews for years. So did his top aides. When Caro took on Johnson, most of LBJ’s aides were and friends and family were circumspect. So Caro draw a set of concentric rings on a piece of paper.

The innermost circle with his family, friends, and close associates, and I was prepared to believe that he could keep me from seeing them, and probably the persons in the next circle or two, also. But surely, I felt, there would be people in the outer circles – people who knew him but were not in regular contact with him – who would be willing to talk to me. And, in fact, there were, and, as I was later to be told, Commissioner Moses was more and more frequently encountering people who, unaware of his feelings, said that this young reporter had been to see them.

To know a subject, Caro suggests, you need to find a way to get the subject’s colleagues and family and neighbors talk. You can’t just show up and expect people to talk. You have to show a commitment to really know the subject. And so Johnson moved to Texas. It was then that people started to tell him more than the hackneyed old stories: “I began to hear the details they have not included in the anecdotes they had previously told me – and they told me other anecdotes and longer stories, anecdotes and stories that no one had even mentioned to me before–stories about a Lyndon Johnson very different from the young man who had previously been portrayed.”

Interviewing

Interviewers have to be persistent and reach their subjects on a deeper tlevel than they even understand themselves. But sometimes they also need to be manipulated. As a reporter for Newsday, he was working with a reporter named Bob Greene to expose a charitable organization that was using “the bulk of its money on a luxurious lifestyle for the director and his mistress.” They had the evidence but needed the organization’s director to acknowledge it. “When you talk to him, don’t sit too close together,” their editor, Alan Hathway, told them. “Caro, you sit over here. Greene, sit over there. You fire these questions fast—Caro, you ask one; Greene, you ask one—I want his head going back-and-forth like a ping-pong ball.” The ploy worked. the director got rattled and revealed more than he intended. They had their story.

After Caro worked on The Power Broker for years, Moses agreed to a series of long interviews. Caro had done so much work that Moses had to give him time now if he wanted his point of view in this definitive work. Now Caro’s task was to take in all that Moses had to offer.

Silence is the weapon, silence and people’s need to fill it–as long as the person isn’t you, the interviewer. … When I’m waiting for the person I’m interviewing to break the silence by giving me a piece of information I want, I write SU (for Shut Up!) in my notebook. If anyone were ever to look through my notebooks, he would find a lot of SU’s there.

It’s just a dogged pursuit of facts. No good interview is possible without the research to back it up. You interview someone to learn more things–but before that, you need to have enough facts to push and prod the subject. When you know some significant part of the story, then listening becomes golden.

When interviewing people, Caro pushes them–to the point of annoyance–to describe what they saw and heard and felt. It’s not enough to say the limo ride from the Capitol was quiet; Caro wants to know what that quiet was like. It’s not enough to decry the viciousness of racism; Caro wants to know what it felt like for blacks to attempt, time and again, to register to vote and get rejected by cracker election officials.

If you talk to people long enough, if you talk to them enough times, you find out things from them that maybe they didn’t even realize they knew.… My interviewees sometimes get quite annoyed at me because I keep asking them “What did you see?” “If I was standing beside you at the time, what would I have seen?” I’ve had people get really angry at me. But if you ask it often enough, sometimes you make them see.

Caro prods interviewees to remember what it was like to sit in a particular place or walk along a particular road. Sometimes they tell him but it doesn’t make sense until he recreates the scene.

One scene is especially notable. When he first came to Washington as a congressional assistant, LBJ would arrive at the office out of breath. On the last part of his morning walk to the capitol, he broke into a run. Why? Caro retraced the steps, again and again, but didn’t notice anything. Then he realized that he should retrace LBJ’s trip early in the morning.

At 5:30 in the morning, the sun is just coming up over the horizon in the east. Its level rays are striking that eastern façade of the capital full force. It’s lit up like a movie set. That whole long facade—750 feet long—it’s white, of course, white marble, and that white marble just blazes out at you as the sun hits it.

With that extra effort, Caro was able to be there–in the same time and place as the excited young congressional aide would would become president–and put the reader in the same place. That one moment captures the excitement better than anything else could.

Puzzles

All great stories present puzzles inside puzzles. The ultimate puzzle is about the characters and the vents of the story. Who is he? What makes him tick? Why does he do what he does? Why did X happen and not Y?

To understand complex topics, look for the moments when something big changes. Notice the turning points, even if no one has ever seen those moments that way before. While interviewing the LBJ story, poring though archives, Caro noticed a change in tone in letters written to LBJ early in his congressional career. In his earliest years in Congress, LBJ looked like every young legislator. He sought the favor of his seniors. Then the letters showed something different. “in which they were doing the beseeching, asking for a few minutes of his time. What was the reason for the change? Was there a particular time at which it had occurred?” Caro pursued the puzzle until he discovered the reason. Johnson got monied interests to funnel contributions to Congressmen though him. Suddenly LBJ was the money man on the hill.

One of the oldest puzzles concerned the 1948 Senate race. After Coke Stevenson was declared the winner, a recount in Precinct 13 found 200 extra votes for Johnson and two for Stevenson. That gave the election to LBJ. Most people treated the election as a “Texas size joke, with stealing by both sides.” But Caro needed to know. After searching bars and other old haunts, Caro finally found Luis Salas, the man behind the discovery of those extra votes.For years Salas lived in Mexico, but he had recently moved back to a trailer park in Texas. Salas not only agreed to talk, but also to share his memoir of the incident. He wrote the memoir because “I am running short of time, feel sick and tired… Before I go beyond this world, I had to tell the truth.” No one had ever gotten this first-hand account–this confession–before. And so the mystery was settled. LBJ did steal the election.

Exemplars

Caro’s books are known for their heft. He’s written thousands of pages on his two subjects. He offers detailed examination of complex topics and intimate portraits of the people and places and scenes. But in those books are smaller stories that serve as parables for the larger epics. They are intimate accounts of ordinary people and how their lives were affected by these two political giants.

The most excerpted section of The Power Broker, a chapter called “One Mile,” tells how Robert Moses built the Cross-Bronx Expressway right through the neighborhood of East Tremont. This route led to the demolition of 54 six- and seven-story apartment buildings. He could have shifted the highway just two blocks and only demolished only six buildings. Community people asked him to do just that but he refused. Caro’s story is a devastating story of the destructiveness of power–and the callousness of the man behind it.

In the LBJ books, Caro tells of how electrification transformed the lives of rural Texans … how civil rights laws overturned brutal systems of racism … how LBJ began to use his ruthless tactics to control campus politics as a college student … his his brief period teaching in rural Texas have him empathy for the poor and dispossessed. These stories ring with energy and power because they are about ordinary people and how their lives were shaped by the was power was deployed.

Being There

To understand LBJ, Caro learned, he had to understand his father Sam. As he learned Sam’s story, Johnson’s cousin Ava decided Caro needed a reality check. He needed to see how foolish Sam was to settle in the Hill Country. So she told Caro to drive her to the Johnson ranch. When they got there she told him: “Now kneel down.” He did. “Now stick your fingers into the ground.” He could not move the whole length of a finger into the ground. The land had almost no topsoil. It looked like a lush land with its endless expanse of grass. But it could not produce anything. Sam was snookered by the appearance. Lyndon vowed not to make the same mistake.

Most biographies depicted Johnson as a popular BMOC in college. But Caro heard lots of rumblings that this was a myth. One of Johnson’s old classmates, Ella So Relle, grew agitated when Caro kept asking questions. “I don’t know why you’re asking all these questions,” she said. “It’s all there in black-and-white.” Where? In the Pedagog, the college yearbook. Caro had read it and found nothing of interest on Johnson. He want back and looked his his copy and again found nothing there.

He called Ella and asked her to tell him what pages she was talking about. Those pages had been skillfully razored out of the book. When Caro went to a local used bookstore to see other copies, the pages in question were also cut. Finally he found a complete copy, filled with stories alluding to Johnson’s early days as a political manipulator.

Writing

Before writing the actual draft of a book, Caro tries to articulate the point he wants to make. He writes one to three paragraphs that summarize the driving idea of the book. The process can take weeks. So what might this summary say. Caro summarizes his first Johnson book, The Path to Power:

That first volume tries to show what the country was like that Johnson came out of, why he wanted so badly to get out of it, how he got out of it, and how he got his first national power in Washington through the use of money. That’s basically the first volume–at the end of it, he loses his first Senate seat, but it’s pretty clear he’s going to come back. When you distill the book down like that, a lot become so much easier.

With that North Star, he begins to write an outline of the book. He posts those pages on his wall so he can see the whole book at a glance. Then he writes detailed outlines of chapters, which is really the whole chapter without the details. A long chapter might get a seven-page brief. Then, each chapter gets its own notebook, filled with all the chapter’s stories and quotations and facts.

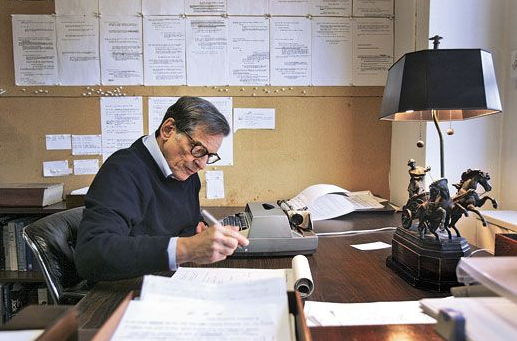

Caro writes his drafts longhand on white legal pads, three or four times. Then he types these drafts on an old electric typewriter, using legal paper and triple spacing to leave lots of room for editing. Some drafts have more pencil marks than type.

He starts each day by reading the previous day’s output. “More and more frequently when I reread the stuff I wrote in the late afternoon the day before, it was no good and I had to throw it out. So there was no sense in working late; I stop earlier now.”

Writing takes enormous concentration. “Any interruption is a shock, a real jolt,” he writes. Once, working at the Frederick Lewis Allen Room at the New York Public Library, someone tapped his shoulder to go to lunch. “I found myself on my feet with my fist drawn back to punch the guy,” Caro says.

Research and early drafts make art possible. It’s the Michaelangelo Principle: To produce art, you chip and carve a massive hunk of granite until you find, inside it, your own David. Caro’s original drafts of The Power Broker were more than a million words. He cut that down to 700,000 words.

Style

When writing the preface for The Power Broker, Caro struggled to describe just how totally Robert Moses had transformed New York with bridges, highways, tunnels, beaches, parks, housing, dams, and more. Then he remembered reading Homer’s Iliad in college. Homer listed all the nations and all the ships that went to fight in the Trojan War. The epic’s use of dactylic hexameter gave this list a sense of drama. And so Caro, in describing the long list of Moses projects, made them sail across the page, as if ships going to Troy.

“I thought I could have a rhythm that builds, and then change it abruptly in the last sentence,” Caro remembers. “Rhythm matters. Mood matters. Sense of place matters. All these things we talk about with novels, yet I feel that for history and biography to accomplish what they should accomplish, they should have to pay as much attention to these devices as novels do.”

Genius

Lyndon Johnson was one of America’s greatest tragic heroes, a Shakespearean figure who transformed a nation but got brought down by his own demons. Johnson, Caro says, had “a particular kind of vision, of imagination, that was unique and so intense that it amounted to a very rare form of genius – not the genius of a poet or the artist, which was the way I had always thought about genius, but the type of genius that was, in its own way just as creative: a leap of imagination that could look at a barren, empty landscape and conceive on it, in a flash of inspiration, a colossal public work, a permanent, enduring creation.”

Here’s my definition for genius in a nonfiction writer: Someone who is intensely curious about the world and how it works, someone who wants to show it whole but also reveal its contradictions. To achieve this ambition, the writer restlessly explores issues that others consider settled or uninteresting or beyond anyone’s ability to know. This restless exploration depends on a commitment to facts–gathering them, checking them, making sense of them. And then, when the facts are gathered and organized, they are used to construct a work that reveals something fresh about how the world works.

By this definition, I think we’d have to say that Robert Caro is a genius. His body of work is as great as that of any biographer–or maybe any nonfiction writer, or maybe even any writer–now alive.

Before you go . . .

• Like this content? For more posts on writing, visit the Elements of Writing Blog. Check out the posts on Storytelling, Writing Mechanics, Analysis, and Writers on Writing.

• For a monthly newsletter, chock full of hacks, interviews, and writing opportunities, sign up here.

• To transform writing in your organization, with in-person or online seminars, email us here for a free consultation.