The brain loves simple, clear tasks. When you only search for one problem at a time, you stay sharp. You spot problems better and don’t run out of energy.

Therefore, follow this simple approach to editing: Start big, working your way to smaller issues, one challenge at a time. Let’s see how to do it.

Start by blocking sections. Most writing—even pieces as short as a two-page memo or a newspaper op-ed article—consists of a number of chunks. Each chunk presents distinct ideas.

Put a label on each major section. It’s easier to manage a handful of well-marked sections, each with well-marked parts, than a piece with 75 unmarked parts.

For each section, express a clear “umbrella” concept. Everything in that section should fall under the umbrella concept. If any ideas veer off topic, cut it or move it.

Make sure your whole piece starts and end strongly. Make sure all its sections do as well. Consider writing the first and last paragraphs before anything else. If you know the beginnings and endings of your journeys, the pieces in the middle sort themselves out easily.

Label ideas in paragraphs. Every paragraph should take the reader on a simple journey, starting and finishing strongly. Make every paragraph a mini-journey, following Aristotle’s narrative arc. Make sure you can explain this mini-journey with a simple tabloid headline. Make sure just glancing at your paragraph labels reminds you, instantly, about what journey it takes the reader. (More on this point in a moment.)

Check sentences for the Golden Rule. Make sure every sentence takes a journey, starting and finishing strongly.

Find the modifiers that make sentences run on and on. Sometimes it seems that crafting a simple sentence is the toughest chore of writing. As our minds whir with ideas, we get tempted to veer off track. Then we fail to make simple points.

Often, we get off track with prepositional phrases. Prepositions, remember, express relationships between things. The most common prepositions—of, to, in, for, on, with, out, from, by, and out—are among the 37 most commonly used words in the English language.

Prepositional phrases offer details about the subject. Notice how the prepositions work:

• Franklin Roosevelt was the son of a wealthy family from Hyde Park.

• Jimmy Carter came from a town in southern Georgia.

• I once lived in a house by the side of the Mississippi River.

These prepositional phrases provide useful information. But when you put too many of these ideas into a sentence, you lose sight of the main action—who’s doing what to whom. The reader struggles to keep up with the twists and turns.

Let’s look at an example from an academic history journal:

After the Second World War, the general drift of American public opinion toward a more liberal racial attitude that had begun during the New Deal became accentuated as a result of the revolution against Western Imperialism in Asia and Africa that engendered a new respect for the nonwhite peoples of the world, and as a result of the subsequent competition for the support of the uncommitted nations connected with the Cold War.

In this 72-word sentence, the author uses 16 prepositions—after, of, toward, during, as, of, against, in, that, for, of, as, of, for, of, and with. Each one adds a new thought, but pulls the passage off course. It’s overwhelming, like asking a driver to turn 16 times to travel a short distance. To rewrite that passage, I broke it up. Look at this new version:

After World War II, Americans adopted more liberal attitudes about race. The New Deal began this process. Revolutions against imperial powers in Asia and Africa created new respect for the nonwhite populations. The Cold War also prompted the U.S. to consider how racial strife damaged America’s image.

The revision breaks one monster sentence into three ordinary sentences. It uses 47 words, 25 fewer than the original. And it uses only five prepositions—about, against, in, for, and in—instead of 16. That’s fewer than two prepositions per sentence—a more manageable number of twists and turns for the reader.

Root out repetition and needless words. Most drafts contain meandering, repetitious, and clumsy phrasing.

Too often, writers repeat ideas by using just slightly different words for the same thing. Politicians say they will care for “each and every” voter. Business executives tell us that “first and foremost,” we have to cut costs. Advertisements offer a “free gift” for opening a bank account. We also hear people talk about future plans, end results, armed gunmen, unconfirmed rumors, living survivors, past history, actual experience, advanced planning, and natural instincts. Each of those expressions repeats a simple idea. So cut ’em!

Eliminate hedges and emphatics. Too often, when we want to emphasize a point, we use vague language.

A hedge limits or qualifies statements. By expressing conditions or exceptions, the hedge tells the reader, in effect, “I’m not completely sure what I’m going to tell you.” Hedges include words like almost, virtually, perhaps, maybe, and somewhat. Such words pretend to modify a point, but give the reader little real information. Writers use them to avoid taking a clear, distinct stand.

An emphatic shows strength of conviction but lacks adequate evidence or certainty. Emphatics assert something without showing it. As everyone knows is a classic emphatic. So are of course, naturally, understandably, usually, almost always, interestingly, and surprisingly. Consider this passage from a portrait of Andrew Carnegie:

The Carnegies were poor—very poor—but not quite destitute. Their home was a hovel, but not quite a hellhole. Allegheny, Pittsburgh, and the environs were ugly and just plain awful. But there were worse places in the world then, and there are now.

The passage tells us little. The author wants to emphasize points with locutions like very poor and just plain awful; he backs off his points when he refers to a hovel, but not quite a hellhole. The author would do better note the food the Carnegies ate, the clothes they wore, the size and furnishings of their home, and whether they had heat and water. Details, not emphatics and hedges, offer a clear picture.

Address details, one by one. Now address all the other problems: spelling and punctuation, noun-verb and non-pronoun agreements, adjectives and adverbs, dangling modifiers, passive verbs and imprecise nouns.

As you move from big to small problems, you’ll see something amazing. By fixing the big problems, many smaller problems disappear. Why? When we structure a piece poorly—with the wrong chapters or sections, arranged poorly—we lose clarity about the smaller points. Because we’re fuzzy on the big stuff, we’re fuzzy on the little stuff.

If you get the big pieces right, the smaller pieces take care of themselves.

Read to Others

Until modern times, most people experienced great literature—or even news reports—by listening to others read. This oral tradition, in fact, produced the greatest works of literature. Storytellers would recount, from memory, great myths, histories, comedies and tragedies, philosophical works, and religious works. The constant retelling polished these works over the centuries. Audiences acted like focus groups. When a phrase worked with audiences, it stayed; when it didn’t, it got cut.

The best way to edit is to read drafts to other people. If a passage sounds unclear or clunky, we see it in the restlessness or confusion of our audiences. Unfortunately, most writers these days labor in isolation. We read our drafts, silently. And so we lose the opportunity for feedback.

Read Aloud

Reading aloud helps you find clumsy or ungrammatical passages. Any time the reader stumbles over a phrase or repeat ideas, you know something’s wrong. It’s like putting on glasses and noticing the blemishes on someone’s face. Something easy to overlook becomes all too visible.

When the words flow easily, we know that we have done our job. So read everything aloud. Or transmit drafts to your Kindle and listen to a synthesized voice read it back. Ask yourself: Does one idea lead to the next? Can you follow the story or argument? Does the piece stay on track? Also pay attention to the technical issues, like typos and clumsy, wordy, or vague passages.

Pick up a great book—a classic—right now. Read something by Truman Capote or John McPhee or F. Scott Fitzgerald. Find the poetry of Wordsworth or Shakespeare or T.S. Eliot or e.e. cummings. Or find a well-edited magazine, like The New Yorker or The Atlantic. Read a passage aloud. Notice how the words glide.

Power Editing

Reading aloud has its own problems. It takes an awful lot of time. If you’re editing a book or a long article, it’s impossible to read without getting tired or distracted. After a while, you lose your focus. You’re just mouthing the words, without really paying attention to word choice, syntax, and so on. At some point, you start reading silently — which defeats the whole purpose. Soon, you’re moving as slowly as Heinz ketchup coming out of a bottle.

That’s what has happened with my new manuscript. I sit down to read it aloud, I get five or ten pages into it, and I drift off. Or the phone rings or email pings.

Frustrated, I asked myself when I got to work this morning: How can I do this faster and better? The answer: Do it faster and you’ll do it better. In other words, read the manuscript as fast as possible. Race through the text, as if you’re hopped up on caffeine or you’re double-parked. Let’s call it power editing.

Reading a text fast actually reveals the clunky passages better than reading at a normal pace. You can read good writing fast, but flawed writing causes you to mess up. So you not only get through a text faster, but spot problems better. Every pothole on the road shakes you up. So you mark the problematic passage or edit it on the spot. And then you continue.

You take the brain out of its comfort zone. When you read fast, you have to activate your whole brain. You have to concentrate. Your whole body gets into it.

P.S. This is exhausting. Maybe you can only do 2,000 to 5,000 words at a time. Most people, of course, don’t have to edit much more than that. If you’re editing a book or long report, you might have to do it in spurts. But you’ll get better results, faster, than with the slow Heinz-ketchup approach.

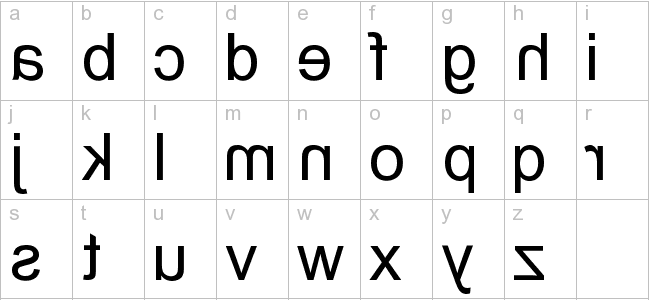

Sdrawkcab krow

To combat familiarity, read backwards. Read the last paragraph first, then the penultimate paragraph, then the ultra-penultimate paragraph, and so on. You will be surprised at how easily you can spot—and kill—bad and repetitive writing.

By reading backwards, you also see the piece’s outline clearly. Does paragraph 17 follow paragraph 16 logically? Does paragraph 7 develop the ideas of paragraph 6?

Athletes work backwards all the time. They imagine the result they want—say, a tennis ball landing in the corner of the court, just beyond the reach of the opponent—and then think backwards to imagine the sequence of events leading to that result. After imagining the ball landing in the ideal spot, a tennis player can imagine the ball flying across the net … then hitting the ball … then bringing the racket back to hit the ball … then getting into position, planting feet … then seeing the opponent hit the ball over the net … and so on.

Think of writing that way. Think of how you want to complete a passage, and then what came before, and then what came before that, and so on.