Charles V. Bagli is the best investigative reporter on real estate in the American capital of real estate.

Reporting for The New York Times, Bagli tracks the big deals and the seismic shifts of the city’s development and land use—and the often-dirty politics of the industry.

Journalism was not on Bagli’s mind until his late 20s. He went to Boston University to become a filmmaker but the school of communications required students to wait until their junior year. By that time, he was involved in the antiwar movement and was working with the radical historian Howard Zinn. He worked as a labor organizer for six years. Then, as a husband and new father, he says, “I decided I had to grow up.” So he applied to be a plumber’s apprentice in Springfield, Massachusetts—and he applied to Columbia Journalism School. He got into Columbia and took his family to the big city.

Journalism was not on Bagli’s mind until his late 20s. He went to Boston University to become a filmmaker but the school of communications required students to wait until their junior year. By that time, he was involved in the antiwar movement and was working with the radical historian Howard Zinn. He worked as a labor organizer for six years. Then, as a husband and new father, he says, “I decided I had to grow up.” So he applied to be a plumber’s apprentice in Springfield, Massachusetts—and he applied to Columbia Journalism School. He got into Columbia and took his family to the big city.

Right away, he had doubts. A professor heavily critiqued his first submission. “The professor just rips it apart and I’m sitting with my head in my face and I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’ve done the wrong thing,’” Bagli remembers. “Fortunately, I hung around and improved.”

In retrospect, Bagli had the right stuff all along. He loved telling stories, even if his writing was “just throwing words on paper and hoping people would wade through to understand it.” His proudest moment in high school was screening a short movie that ended with the hero “running across a field and there’s a pretty woman and the Dylan song comes up, ‘If dogs run free, why can’t we?’” The audience loved it. Heady stuff.

Bagli also liked spending time with people from diverse backgrounds. “I always get energized when I bump into people. As a journalist I am constantly meeting new and different people.”

Because of his organizing background, Bagli figured he would be a labor reporter—“not knowing there weren’t labor reporters anymore.” He wrote for the Brooklyn Phoenix, Tampa Tribune, Morristown Daily Record, and New York Observer before landing with The New York Times 20 years ago.

Charlie Bagli met with my class “Writing the City,” at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, in October 2018. Here are some excerpts from our class conversation.

Bagli decided to embrace covering real estate, one of the orphans of journalism. Real estate is a difficult beat for two reasons. First, real estate coverage often involves fluffy PR pieces packaged with advertising, so reporters run into trouble with editors when they take a critical approach. Second, real estate is a complex topic that drives away reporters who want to rise quickly by covering sexier beats.

I wasn’t intimidated. I became self-taught. When I got a job at The Observer in 1987, I was covering the east side of Manhattan, from 14th Street to 96th Street, and there was a building boom going on. One by one, I met the developers and their lawyers and their PR people—and their opponents on projects too—and I made my own maps of who owned what. I set out to know the subject well so people couldn’t BS me. I wanted to become something of an expert.

The beat I have covered for 30 years is at the intersection of politics and real estate in New York. I thought real estate was one of the twin pillars of the economy [with finance]. You could not know New York without knowing real estate. In New York the mayor is a powerful figure and the city council not so much—except in one area, which is land use. Look at every politician, where they get political contributions, it comes from real estate. Real estate gives inordinately at both the city and the state level.

To make complicated topics understandable, a real estate reporter has to avoid insider lingo and find pithy ways to express complex, mind-numbing issues.

Because the subject is complicated, you have to constantly put yourself in the mind of the reader. What do they know? What can they get through? I can’t use jargon. Do you know the term ULERP? It means Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. I don’t use that term in a story. I’m always looking to break things down in a brief and useful way.

So you have little techniques. During a brief stint as a business reporter in New Jersey, I was doing a story about popcorn. I can’t remember if popcorn was going up or down. Anyway, I wanted to illustrate how much people ate popcorn, I calculated how much space in Giants Stadium would be filled with all the popcorn kernels people used in a year. It’s a lot of work for one sentence, but people know what you’re talking about.

“Creative destruction” is a constant subject of Bagli’s work. In 1967, families in the Lower East Side were forced out of their homes to make way for an urban renewal project. After the buildings were demolished, real estate and political interested battled over the area. Finally, the Bloomberg Administration brokered a deal to build new housing and former residents were invited back. That’s when Bagli met David Santiago, who was planning to move one of the units.

“Creative destruction” is a constant subject of Bagli’s work. In 1967, families in the Lower East Side were forced out of their homes to make way for an urban renewal project. After the buildings were demolished, real estate and political interested battled over the area. Finally, the Bloomberg Administration brokered a deal to build new housing and former residents were invited back. That’s when Bagli met David Santiago, who was planning to move one of the units.

I always though the different neighborhoods were what made New York so interesting. I loved walking through garment district, that was one of the few places where you could see people actually working as opposed to disappearing into glass towers. There was the printing district, the flower district. These places are gone now.

In the 1960s they ousted all these Puerto Rican families and said they were going to build new housing and nothing was built for 50, 60 years—they were parking lots all that time. They never made good on the promises. Racial and ethnic politics was why nothing was built. There had been a series of coops in that neighborhood. Every time there was a plan to build housing, the coops fought it. They were able to defeat every attempt. They said we need jobs, not more housing—they didn’t say they didn’t want minorities.

They were opening the first building and a lot of people were returning to the neighborhood. I found David Santiago. He was a restaurant guy. Then a couple weeks after the building opened, I got a call from one of the activists and she said, “David died the day he was throwing this housewarming party.”

It was so interesting when he was alive to talk about the neighborhood. It was a poor polyglot neighborhood, with the Puerto Ricans and the Italians mixed in with the Chinese and a large Jewish community. David had these memories that were really interesting—and increasingly forgotten—as this tsunami of gentrification washed over Manhattan and Brooklyn.

His was a good story to tell because he reflected what happened in that neighborhood. His family was pushed out when he was seven. He had a wisdom about what the neighborhood was about. He had lied about his age and joined the Marines. Every experience was different but he reflected something about the whole neighborhood. He talked about the mobster in the social club that would give him a coke in green bottles.

His death gave me the room to talk about him. So I was sucking up all the details. A lot of stuff doesn’t get in, but of you don’t have it all, you don’t get that one telling detail that just makes the story.

As an established investigative reporter for The Times, Bagli has freedom to roam around the city and explore all possibilities. That means spending time on the street and following up tips. Some tips lead nowhere. Others lead to scoops.

Sometimes you get a call out of the blue. You know Felix Sater, the Russian pal of Trump? I write about him in 2007. I got an anonymous call telling me about this guy Felix who changed one letter in his name so you couldn’t Google his past. One night he’s celebrating at a bar on Third Avenue and he gets in an argument and breaks a Margarita glass and stabs the guy in the face—he guy had 100 stitches—and he runs and the cops caught him. He was part of a mob scene of Wall Street, pump and dump. He was also working on Trump Soho, a condo/hotel. It was a financial disaster.

So this [tipster] is telling me these stories. I’m thinking, this is great if it’s true, but how much time am I going to have to figure out whether its true? You’re constantly doing triage and sometimes you’re right and sometimes not.

Turns out everything this guy said was true. I didn’t know his name but people call you all the time and sometimes they’re BS. I heard when he was indicted for the Wall Street scam and I got the police report when he stabbed that guy in the bar. I called American University, which had a center that tracked Russian mobsters and his father was in the mob. I figured out my source—he had been indicted with Felix for this scam on Wall Street and he was a straight guy and the worst day of his life was when he met Felix. So it was revenge, absolutely.

If you lie to me, I consider it a cardinal sin. If I fail to ask the right question, that’s only a venal sin. This is the Catholic in me. I want to put the fear in them, that if they ever lie to me I will kill them. It turned into a great story. I thought it would break up his relationship with Trump but it didn’t.

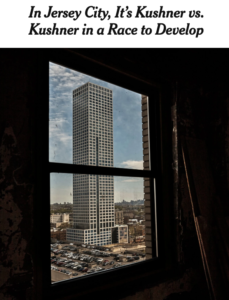

Sometimes the best stories are outside the center of the industry. Jersey City and other markets across the Hudson River have boomed as New York real estate prices have pushed people out of the city—and as developers have speculated wildly.

I did a story recently about Journal Square in Jersey City. I walked around and thought this is not a neighborhood. There are so many streets criss-crossing. Its hot because the waterfront is done, Grove Street is done. The next stop on the PATH train is Journal Square. So it’s going to happen.

You have the two Kushner brothers who hate each other and they want to build three towers each. It’s a recipe for disaster. You can’t put that many units in a neighborhood all at once. They compete with each other. Murray Kushner’s first tower is up. Charles had an empty lot and lost authority from the city. He thinks he’s persecuted because of his relationship with the Trump administration.

You have the two Kushner brothers who hate each other and they want to build three towers each. It’s a recipe for disaster. You can’t put that many units in a neighborhood all at once. They compete with each other. Murray Kushner’s first tower is up. Charles had an empty lot and lost authority from the city. He thinks he’s persecuted because of his relationship with the Trump administration.

I still wonder whether that neighborhood is going to turn. The next stop is Harrison, where they’re building like crazy near that soccer stadium. A lot of public money, idiotic money I thought. Ten to 15 years later, they’re not building. It’s a tiny community across the river from Newark.

There’s a lot of outflow from New York because New York is wildly unaffordable. If you’re on the outer rim with public transportation you’re in good shape. You can get from Newark to Penn Station in 15 to 20 minutes. Try to get from Times Square to Coney Island in less than 90 minutes.

Before going all-in on a story, Bagli likes to visit the neighborhood and see what it’s like.

I’m thinking about doing a story on the Museum of Natural History. They want to expand [by] 230,000 square feet. About 11,000 square feet, or a quarter acre, would encroach on Theodore Roosevelt Park. Some residents have sued to stop the expansion. I want to go and see how it’s used—how many are local people walking the dog or teaching a kid to ride a bike, and how may are tourists using the museum. You could say it’s only 100,000 square feet, but sitting in the park and getting seeing who does what the story.

There are real tradeoffs here. Is this a matter of “rules are rules,” so they shouldn’t get the park space? Or should other considerations come to play? You’ve got to be there and know the people in the area—who lives and who are the businesses.

Before deciding whether to write the story, Bagli decided to attend a court hearing on the activists’ challenge of the museum takeover as “arbitrary and capricious.” Even if a museum’s use of a quarter-acre of public space might be seem a minor issue in a city of 8 million souls, it illustrates the broader issue of the private use of public land.

This issue of parkland is a big thing in New York City. In Queens, at Flushing Corona Park they’ve already carved off for a big piece for tennis and then the Mets stadium and in the Bloomberg era they wanted to put a soccer stadium there. Why are they handing it over to a privately owned entity and shortchange the rest of the neighborhood?

In the park there’s also some crummy soccer fields and very active leagues. The owners of the leagues say we’ll renovate the fields and run clinics. So you had different views in the community. You had people who were doubled and tripled up in housing and others who lived in community and their kids played soccer and it seemed tantalizing. But it’s more space for private use instead of public use. That’s an issue.