Like other journalists of this late-print/early-digital age, Tina Cassidy has taken on a number of challenges as a writer. And more than most, she has succeeded.

Cassidy was a reporter for ten years at The Boston Globe, where she covered business, politics, and fashion. A Rhode Island native, she published articles in the Providence Journal as a high school student. She studied journalism at Northeastern University. After college she worked for the Boston Business Journal and the Associated Press before joining the Globe.

Since leaving the Globe, she has written books about Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, the process of being born, and, most recently, the battle for the women’s vote.She is now executive vice president and chief content officer at InkHouse, a national public relations and digital marketing agency.

She is active in civic affairs as a board member of the New England Center for Investigative Reporting and as an activist for women candidates and passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. She was a founding member of the Association of Capitol Reporters and Editors, a national organization dedicated to coverage of state and local government.

She is active in civic affairs as a board member of the New England Center for Investigative Reporting and as an activist for women candidates and passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. She was a founding member of the Association of Capitol Reporters and Editors, a national organization dedicated to coverage of state and local government.

She lives in the Boston area with her husband, Anthony Flint, another ex-Globe reporter and author of acclaimed books on architecture and planning, along with their three sons and a Norfolk Terrier named Dusty.

Charlie Euchner: You began your writing career as a journalist. In your years with The Boston Globe, you also worked a number of different beats. Too often, beat writers get stuck in a rut, writing the stale old thing year after year. Can you talk about your experience covering different topics?

Tina Cassidy: I had pretty good self-awareness about when I needed a new beat. The clues included the feeling that I had exhausted interviewing all experts on the topic; that nothing I was writing about was surprising or felt new anymore. Weirdly, it was as if I had a biological clock timed to switch beats — typically every four years. Not sure if that was a coincidence or, as with a college degree, that’s about how long it takes to become an expert on something.

CE: Can you tell me about starting out as a teenager in Rhode Island. What kinds of stories did you do and what kinds of lessons did you learn then, about writing and reporting, that you remembered and applied thereafter?

TC: I wrote some articles for my hometown paper The Cranston Herald, mostly about school-related issues, and I was a stringer for the Providence Journal‘s West Bay briefs section; I think I got paid $25 per submission, which felt like a lot at the time. What I learned is that local journalism is essential, that people really care about what’s going on in their community and that there are stories all around us that go uncovered but shouldn’t. Today’s collapse of local journalism is a dangerous thing. Research has found that when community papers shut down, polarization increases. This is the last thing we need.

CE: Are there any stories for the Globe that you were especially fond of? Can you say a thing or two about them?

TC: “Fond” is not the word I’d use. But the most memorable ones for me were covering the 1996 Super Bowl between the New England Patriots and the Green Bay Packers (there was more drama off the field than on); JFK Jr.’s deadly plane crash; being in New York City on 9/11 and running toward the World Trade Center when it collapsed–and then somehow managing not just to survive but to run uptown in high heels and file a story before the special edition; and covering the 2000 Presidential election, from being on the bus with John McCain to looking at hanging chads in Florida.

CE: How did you make the transition from short pieces to full-length books? Some people think of books as collections of shorter pieces, and there’s some truth to that. But books need not only detailed stories and ideas, but also a sense of wholeness. So what helped you make the leap?

TC: The leap felt more like a continuation for me. I only write nonfiction and I am a compulsive writer who thrives on deadline. (I wish this weren’t the case.) If I sense a good story, I can’t stop myself from writing about it. At the heart of journalism and writing books is either a great story or the attempt to answer a big question.

My first book, about the history of childbirth (Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born) sought to understand how modern birth had gone so off the rails. I wanted to survey the historical and cultural landscape to see why it was that every generation and every culture had its own way of giving birth as a way to put modern birth in perspective.

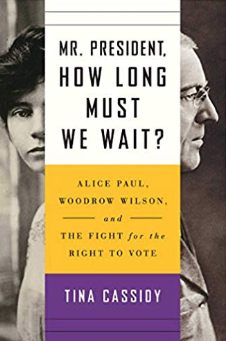

My latest book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson and the Fight for the Right to Vote, is a great story that had not really been told before, pitting a little-known suffragette against a president whose multiple biographies may include a paragraph on suffrage (and his opposition to it) but little more. So it was a blue sky topic for me.

CE: Who are some of your role models as writers? Who do you try to emulate? What “tricks of the trade” do they offer to you as a storyteller, explainer, and book author?

TC: I’ve always admired nonfiction writers such as Hunter S. Thompson, Joan Didion and Tom Wolfe, who bring a journalistic eye and curiosity to their wildly different styles of writing. I can’t say I try to emulate anyone but I have worked hard to change my own writing style as I transitioned from journalism to writing books.

My first book editor, the wonderful Elisabeth Schmitz of Grove/Atlantic, told me to slow down my writing. Pacing is something they don’t teach you in journalism school. So I’ve worked on that. I also have to work at showing, not telling. I am always editing myself on that front.

CE: What’s your biggest challenge as a writer? How do you manage problems? Are you a plotter or a pantser? What “tricks of the trade” have you picked up over the years.

TC: I am a plotter. Structure is the first thing I figure out. It doesn’t mean it doesn’t change, but I need a road map to clarify the story or the question I need to answer — to proof it out. For my book on birth, it was about organizing millennia of history not chronologically but around subjects such as pain, fatherhood, postpartum.

For my book on Jacqueline Onassis (called Jackie After O) it was a tight chronology of one transformative year. So I built the structure, month by month, on a timeline. For my current book on Alice Paul, the heart of the book spans Wilson’s two terms as president. Plotting that story arc was fun but most challenging!

CE: Can you reflect on living in a writing household? I assume that you and Tony have lots of conversations about reporting, research, and writing. That’s very cool.

TC: Living with another writer means someone is always picking up the slack for the other. When I’m on book deadline, my husband is managing more kids stuff and meals and vice versa. It also means we truly understand the exhausting agony that writing induces, we can encourage each other and help each other get unstuck. Of course, there is also the brutally honest feedback (often accurate and helpful) that we give each other. My husband is always my first editor, though he doesn’t really have a choice because we live the process together. Thankfully, he is a brilliant thinker and writer.

CE: Tell me about your new book on the women’s suffrage movement and Woodrow Wilson. It’s a classic setup–pitting fallible protagonists against a fallible antagonist. How did you move from topic to story? What were some of the surprises and revelations for you, both about the subject and the writing process?

TS: I was scrolling twitter on vacation and came across the trending hashtag for #womensequalityday, which celebrates the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920. I clicked and within an hour, learned about the leader of that suffrage movement, Alice Paul. The next logical question for me was what did the president think of Paul? Turns out, Wilson was the perfect foil – he did not believe the Constitution should give women voting rights. I was surprised to see that many Wilson biographies barely mentioned suffrage, and if they did, it was brief. Paul had been relegated to more academic biographies. I saw an opening and enjoyed weaving these two individuals together.

Excerpt: ‘The Advancing Army’

The following is an excerpt from Tina Cassidy’s new book, Mr. President, How Long Must We Wait? (Atria/Simon & Schuster, 2019), 304 pages

The women slowly made their exit from the East Room and returned to their new headquarters. After four years of toil and hardship in the damp basement on F Street, the CUWS, NWP, and the movement Paul reignited, were finally in a sunlit space, in a place of prominence. Cameron House stood at 21 Madison Place, on the edge of Lafayette Park—the green space in front of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The building—a wide, three-story, brick townhouse—had several benefits. First, it was visible and just two hundred steps away from the White House; the Wilsons could see the suffrage flag fluttering from its perch on the third-floor balcony. Second, there was ample space to work and entertain guests—from tourists and strangers walking in off the street to catch a glimpse of the women, to those attending ever-expanding fundraisers. There were also bedrooms to accommodate Paul and others, eliminating their daily commute. Paul was now using Susan B. Anthony’s old desk, a Victorian cylinder roll-top that Anthony’s secretary had donated to the NWP.

When the indignant suffragists walked through Cameron House’s front door, they entered into a great hall with a large staircase and a fireplace that burned eternal. Paul was there, waiting for them, ready to stoke their anger as they dropped into comfortable chairs in front of the flames and asked the question again: How long must we wait?

When the indignant suffragists walked through Cameron House’s front door, they entered into a great hall with a large staircase and a fireplace that burned eternal. Paul was there, waiting for them, ready to stoke their anger as they dropped into comfortable chairs in front of the flames and asked the question again: How long must we wait?

With the women assembled in front of the fire, Paul pitched a carefully orchestrated idea, which she asked Blatch to present. Cameron House. “We have got to take a new departure,” Blatch told them.

“We have got to bring to the President, day by day, week in, week out, the idea that great numbers of women want to be free, will be free, and want to know what he is going to do about it. We need to have a silent vigil in front of the White House until his inauguration in March. Let us stand beside the gateway where he must pass in and out so that he can never fail to realize that there is a tremendous earnestness and insistence in back of this measure.”

So far, with Paul as their leader, the women had marched four years earlier, in 1913, in the largest and most outrageous protest America had ever seen. They had assembled an eighty-car brigade to deliver signatures from all over the nation. They had testified, editorialized, and reorganized. They had formed their own political party. They held May Day parades in nearly every state in the union. They fundraised and actively worked to defeat Democrats. They had a booth at a global exposition, collected a miles-long scroll of signatures, and drove it cross-country from San Francisco. They dropped leaflets from the sky and a banner from the House chamber’s balcony. And they had sacrificed one of their own. On this day, in front of the crackling fire at their new headquarters, with the White House at their backs, they may have been exhausted, but they were neither depleted of ideas nor the passion to continue the struggle.

They listened as Blatch offered a new form of protest. In America, pickets had become a common union tactic, typically ending in violence. But suffragists had been employing the practice as well. Blatch had used pickets in her Votes for Women campaign with the New York Legislature in 1912, so when she delivered her final plea to the women of Cameron House, they stirred.

“Will you not,” she asked, “be a ‘silent sentinel’ of liberty and self-government?”