One of the hardest jobs for writers is describing a complex process. In everyday life, we tend to gloss over the complexities of things. When we turn a car ignition, write a draft of a story, play a board game, cook a meal, or bargain in the marketplace, we pay attention only to the external appearances of things.

But you can’t write well unless you can explain complex processes. Here are a few ideas about this challenge.

The process process

Explaining a complex process is itself a complex process. Such an explanation requires close attention to a number of separate streams, as well as how the streams feed into each other. Each stream depicts a series of events. The streams do not operate independently. Often, the streams feed into each other. So we have to relate the streams to each other–and to the river–to describe the complex process. In the final analysis, this requires mastering the art of signaling.

Defining a complex process

First, let’s define what we mean by complex process. Here’s a tentative definition”

A complex process is a system of separate series of events or relationships, which somehow relate to each other and create a larger whole.

To see what I mean, think of the complex processes we see in cities—the ecology of a park, the economics of a sector, the operations of a business, or the maintenance of order on the street. Each one is complex, involving a number of different streams. The park, for example, involves animal and plant life, weather and other natural processes, the design and maintenance of the space, the usage and traffic at the park, the staging of events, and so on.

An economic sector, to take another example, involves products and markets, workers, technologies, taxes and regulations, and so on.

We would never claim to understand these complex processes unless we could describe their different streams.

Streams of processes

Now, let’s explore what we mean by these separate streams. The stream is simply a metaphor for a sequence of events. Often, the stream can be considered as a description of action. Sometimes, the stream can be considered a description of related ideas.

If you can describe an action, then, you should be able to describe a complex process. Just think of the complex process as a collection of related actions. To describe an action, we say, in effect: First, … Then, … Then, … Then, … Finally, … To describe a complex process, we describe three or four or more such actions.

Suppose you wanted to describe the complex process of a political campaign. We might break it down like this:

Mastering the issues and developing a platform: First, … Then, … Then, … Then, … Finally, …

Fundraising and pursuing elite support: First, … Then, … Then, … Then, … Finally, …

Polling and advertising: First, … Then, … Then, … Then, … Finally, …

Campaigning and public events: First, … Then, … Then, … Then, … Finally, …

As we describe those separate streams, we might note when one stream affects the others. We might indicate, for example, how polling affects the development of a platform. Or we might describe how elite support (like newspaper editors and interest-group leaders) shapes advertising.

Besides describing each “stream” of the process, we also need to capture the unifying themes. Not just with the campaign, but with all such descriptions of complex processes, we need to answer the question: What gives a campaign coherence–or prevents it from gaining coherence?

The elements of a process

To begin any process description, start by identifying all the pieces of the process. By naming and defining these elements, you make it easier to explain how they all relate to each other.

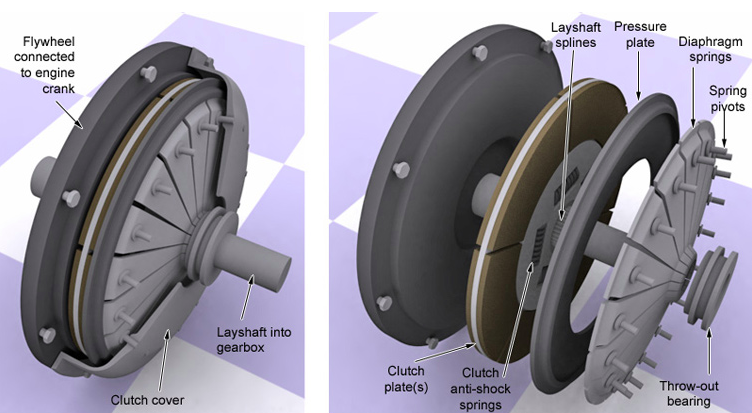

Consider an analysis of a car transmission. As the name suggests, the transmission is the part of the car that transmits power from the engine to the wheels. A slew of parts are necessary for that process, including the input shaft, countershaft, the output shaft, drive gears, idle gear, synchronized sleeves or collars, gear shifter, shift rod, shift fork, clutch, planetary gears, torque converter, oil pump, hydraulic system, valve body, computer controls, governor, throttle cable, vacuum modulator, seals, and gaskets.

Once you’ve defined those terms, show how they operate in a number of separate sequences. First, … Then, … Then, … Finally, …

Most complex processes have different kinds of processes. Your car may use a manual, automatic, or a continuously variable transmission. The processes vary for these different types.

The point is to break things down into their simplest component parts–making sure to define the parts and then to show how they interact.

Not analysis

Do not confuse a description of a complex process with an analysis. The two seem similar. Both show you “how the world works. ” They often show causality. But they differ about their levels of certainty and universality.

Process pieces tend to focus, modestly, on specific, one-and-only streams of events. They say, in effect, “This is what I see.” Analysis pieces tend to focus on general, many-times-over phenomena. They say, in effect, “This doesn’t just happen once or twice; it happens, predictably, over and over.”

Analyses usually take two critical steps. First, they gather enough data to provide a representative sample of the subject. Second, they attempt to identify the causal relationships that determine how the process works.

Reporting, not arguing

A description of a complex process is a kind of reporting job, involving careful observation. A description of a process description does not necessarily show what causes what. It simply lays out what can be observed, what happens and in what setting and in what sequence.

A description of gentrification, for example, shows a range of activities that happen—real estate values changing, newcomers “discovering” the area, risk-takers investing in properties, longterm residents moving out, new lending taking place, “oddball” activities rising, and so on. This description does not necessarily analyze how or why all these activities happen or to what effect.

An analysis, on the other hand, needs to explain the causes of these activities. An analysis needs to gather evidence to make generalizations about these activities.

Details, details, details

As in other kinds of writing, details make these descriptions come to life. But the details differ in process descriptions and analyses.

Process details are like a camera zooming in on action. That camera captures moments for us to notice possible patterns. Often, those details show one-and-only moments, without trying to universalize.

The details of analysis, on the other hand, always look to universalize. They say not “I saw this” but “Everyone will see this, over and over. ”

The anthropologist’s way

You might think of a process piece as a work of anthropology or ethnography. Clifford Geertz, in his classic work The Interpretation of Cultures, uses the term “thick description.”

Geertz calls for “deliberate doubt” and “the suspension of the pragmatic motive in favor of disinterested observation.” One of the writer’s primary jobs is to see things that other people don’t. To do that requires patience. Writers, like anthropologists, need to make a conscious effort to overcome their automatic inclinations.

If we tend to look in one place, we need to make ourselves look elsewhere. If we are naturally interested in one kind of person, place, or event, we need to make ourselves interested in another. This is, in a sense, a Zen practice; it’s all about living consciously.

‘Pre-analysis’

You might also think of a process piece as a pre-analysis piece. To describe a process, you observe patterns. You note the way things work. But you focus on description, not on making judgments.

Geertz argues that careful observation is the beginning of scientific explanation. Only when we observe closely, with as little prejudice as possible, can we “grasp the world scientifically.” In a process piece, you don’t seek to persuade other people to agree with your “take” on how the world works. You do, however, suggest some tantalizing possibilities. And your observations might pave the way for later analysis. But first things first.

A test

Here’s a quick test.

If you’re writing a process piece and you begin to explain why things work the way they do—with the certainty of a scientist—then you’re probably going too far. Stop and get back to detailed descriptions of what you observe.

Observation can be harder

In a way, a process piece can be harder to write than an analysis. Process pieces avoid jumping to conclusions, explaining what it all means. But that goes against our nature.

As neuroscientists have demonstrated, people have a tendency to want to explain everything they see. People are not usually content to simply watch and observe something unfold. They need the need to explain why or why not things happen.

Nietzsche had a term for this pushy desire to make sense of everythin,g even without the necessary information. He called it the “will to knowledge,” which he related to the “will to power.” Both are kinds of compulsions, unhealthy for people trying to live fully.

A life skill

Writing about process requires no small amount of constraint. We have to learn how to be “in the moment,” rather than always jumping to conclusions. That takes great resolve. To avoid getting pulled into the undertow of analysis—the compulsion to explain and persuade—we need to cultivate a sense of mystery and curiosity. But when we master writing about process, we combine the mind of a scientist with the soul of a poet.