The real pros do their jobs and then walk away. They don’t talk about how hard it is to do it. They don’t take shortcuts when it gets tough. They set standards and follow them.

Can you imagine Willie Mays talking about how hard it is to hit a 97-mile-an-hour pitch? Or Winston Churchill moaning about how hard it is to lead a nation when the Nazis are bombing it to hell? Or Einstein grumbling about how hard that whole relativity thing is because, after all, it’s not in any of the textbooks?

No. The pros do their job, period.

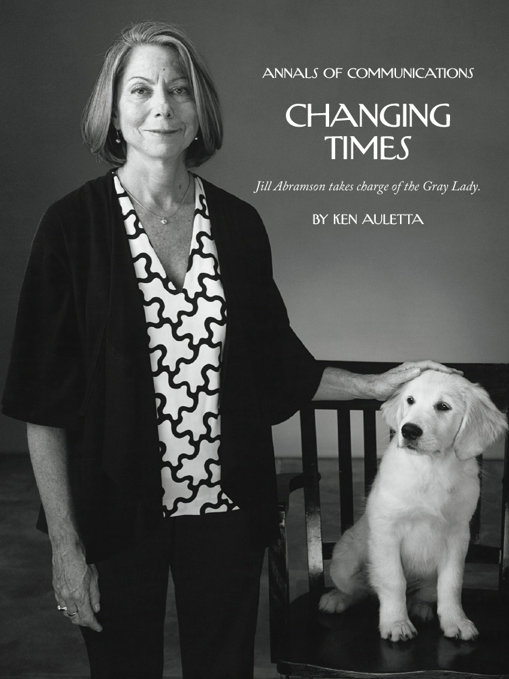

So it is with Ken Auletta, the veteran media reporter for The New Yorker. In his latest effort, Aulatta profiles Jill Abramson, the first woman to be named editor of The New York Times. He shows Abramson for what she is: A talented reporter and editor, a sponge for facts, relentlessly curious, demanding to the point of insulting, and determined to strengthen the core competencies of The Times while leading it into the scary new Age of the Internet.

Auletta reports, you decide. He interviews people from every stage of Abramson’s life and presents all sides of her character. He’s fair, sympathetic but open to others’ critiques of her depth, breadth, and temperament.

Toward the end of the piece, Auletta bring up the ages-old debate about the liberal bias of The Times. In particular he discusses the way that opinion pieces now mingle with straight news throughout the paper. Most of the opinion pieces get labeled “analysis,” which offers the reporter a free pass to say whatever he or she wants to say. But a number of opinion pieces slip into the news pages without such a label, such as Ginia Bellafante’s article about the Occupy Wall Street movement:

The group’s lack of cohesion and its apparent wish to pantomime progressivism rather than practice it knowledgably is unsettling in the face of the challenges so many of its generation face — finding work, repaying student loans, figuring out ways to finish college when money has run out. But what were the chances that its members were going to receive the attention they so richly deserve carrying signs like “Even if the World Were to End Tomorrow I’d Still Plant a Tree Today”?

Now, maybe Bellafante understands the strengths and weaknesses of the movement. But she not only cops a lot of attitude, but also presumes to play the role of strategist for the protesters. And she endorses the OWS gang when she talks about “the attention they so richly deserve.”

Abramson acknowledges that she needs to guard against her own urban bias. She’s a lifelong New Yorker who grew up in its privileged, liberal precincts. She understands that The Times can look down its noses at Flyover Country and the many groups who struggle to make sense of a world that seems to be flying apart.

But when the out-and-out bias of passages like the OWS piece come under debate, Abramson and the other Timespeople talk about how hard it is to keep news straight when so many other publications cop an edgy attitude. As Bill Keller, Abramson’s predecessor as editor, puts it:

Part of the great competition for audience in the twenty-first century is the competition to get beyond commodity news. To add meaning to it. To help readers organize the information into understanding. … The tenor of a front-page news story has changed in the last five or ten years from who, where, when, what, why to more emphasis on how and why.

Yes, readers can be demanding. All day long, we readers hear the headlines on NPR and cable TV and click for updates online. We know the basics — who, what, when, where, and why — by the time we get The Times plopped onto our porches or zapped into our iPad. Readers surely want more than a rehash of what they already know.

But ultimately, it’s a false argument to say that reporters should strut their opinionated stuff because we have so many sources of news.

Take that Occupy Wall Street story. Yes, we hear about it all day. Yes, we want something new when we get our Times. But that doesn’t mean we care what Ginia Bellafante thinks about the struggle. It means we want a deeper, more compelling arrangements of hard-news reporting. Just because Bellafante shouldn’t just repeat what we already know doesn’t mean she should opinionate rather than report.

I would like to see Bellafante and other reporters do twice as many interviews, track down twice as many documents, get twice as much background on the maneuvering of City Hall and unions and liberal funders and police and neighbors and Wall Street workers. No, don’t give us what we already know. Give us deeper, fresher reporting.

Opionators pose the false choice — repeat what you heard yesterday or add the sizzle of opinion — because they still follow the rules of pack journalism. If someone calls a press conference — especially a pol or a celebrity — the Knights of the Keyboard flock to see it. If candidates stage events in Iowa and New Hampshire and South Carolina, they flock to these extravaganzas. If a royal son gets married, they flock to it. If a pol gets caught tweeting naughty stuff, they stake out his house. And so on.

Not that these stories don’t deserve attention. But they don’t deserve hundreds of reporters saying the same thing, as happens all too often.

When you write the same basic stuff that as the rest of the pack, yes, opinionating might seem the best or even only way to stand out. But there is another way. Call it the Wee Willie Keeler Way.

Keeler, of course, was the old-time baseball star who coined the phrase “Hit ’em where they ain’t.” He was talking about hitting a ball beyond the reach of the fielders.

The journalistic equivalent would be to report where they — the rest of the pack — ain’t. Then you get fresh news and don’t have any excuse to fall back on “analysis” and speculation and opinion.

A good model for this principle? None other than Ken Auletta. All he did was report the hell out of his story, make sense of The Times‘s recent years of woe, with a well-organized feast of facts and balanced perspectives.

Without opining or showing off.