This discussion is drawn from The Elements of Writing, by Charles Euchner.

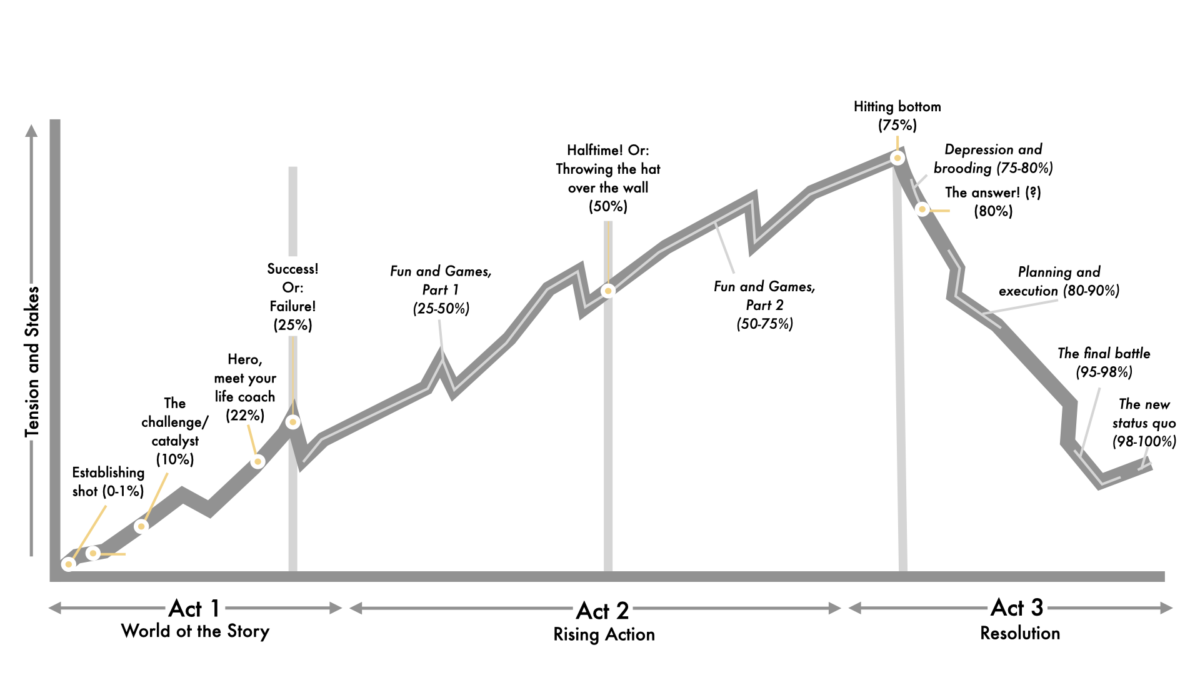

Aristotle’s classic narrative arc has gotten a makeover in the last generation.

With the rise of Big Data and the quantitative analysis of stories, researchers have found ways to advance a story through three acts. These studies have identified specific moments that help define the characters and their quest.

I have examined several of these studies to guide the storytelling process. I have attempted to synthesize their points here.

The authors (and their books) who contributed to this analysis include Joseph Campbell (The Hero With a Thousand Faces), Christopher Vogler (The Writer’s Journey), Robert McKee (Story), Blake Snyder (Save the Cat!), Jessica Brody (Save the Cat! Writes a Novel), Jill Chamberlain (The Nutshell Technique), Jodie Archer and Matthew Jockers (The Bestseller Code), Michael Hauge (Storytelling Made Easy), and James Scott Bell (Write Your Novel from the Middle).

ACT I: HELLO, FLAWED HERO

Act I introduces us to the hero, her likable qualities, and her flaws. By the end of this act, the hero plunges into a struggle that could transform her forever. The act takes up the first quarter of the story.

(1) Establishing Shot (0 to 1%): Something emotional has to happen immediately. Show a single moment with the hero in a challenging place. At this moment, we start to care for and root for the hero.

In this opening moment, the hero states her beliefs about her desires and how the world works. This “setup want” is superficial; it does not address the hero’s true life challenge. Achieving this superficial goal will not solve the hero’s problem; on the contrary, it will reveal the need to take on an even bigger, more existential problem.

This opening scene, then, hints at the hero’s actual need and her flaw.

(2) Statement of Value (5%): In addition to knowing the character’s superficial wants or desires, we also need to understand her deepest desires—even if she doesn’t fully realize them herself.

We can understand the hero’s most profound desire in one of two ways. First, she might inadvertently reveal it by saying something she does not understand. Second, she might act in a way that expresses this desire.

Often, someone else—like the hero’s mentor, sidekick, skeptic, for example—expresses the hero’s more profound desire. Somehow, they know her passions better than she does. After all, she’s in denial; they do not carry her same baggage so that they can see things clearly.

(3) The Challenge/Catalyst (10%): At some point, the hero faces a challenge. The mythology guru Robert Campbell calls this “the call to action.” Others call it the “inciting incident.”

That challenge can come from inside (e.g., the hero’s anxiety, insecurity, or restlessness) or outside (e.g., a broken relationship, job loss, terrible injury, and more). Whatever happens, the hero must—let me underscore must—do something to meet this challenge.

(4) No Going Back (20-25%): After an early period of doubt and debate, the hero moves out of her comfort zone, at least a little. She realizes she has to act. So she engages in the battle—even though she has no idea where it might lead or how it will transform her life.

(5) Hero, Meet Your Life Coach (22%): As the character struggles, she meets someone who can change everything: a friend, mentor, or lover who can push and prod the hero for the rest of the story. This character will force the hero to go deeper than she has ever dared.

It’s going to hurt. The hero’s wounds are deep, and she would rather anesthetize the pain than confront its source. But this new life coach will not let her avoid the deeper reality forever.

ACT II: RISING ACTION

Act II is a struggle over life and death—sometimes literally, sometimes metaphorically. This act, which takes up the middle 50 percent of the story, shows the hero taking on different aspects of her challenge—sometimes winning, sometimes losing.

(6) Success! Or Failure! (25%)—A quarter into the story, the hero gets what she wanted—or at least, what she thought she wanted. This inadequate victory shows that the early desire was superficial and avoidant.

Victory comes with a “catch.” That catch points to the hero’s authentic goal—and frontloads Act II with a batch of more demanding, more meaningful challenges.

(7) Halftime, or Throwing the Hat Over the Wall (50%): As she struggles with her greatest challenge, the hero finally takes bold action. She asks herself: “OK, what’s it going to be? More avoidance—or authentic growth?” She makes irrevocable decisions. She’s “in it to win it.”

Halfway through the story, the hero will experience either a false victory or a false defeat in pursuing her authentic goal.

(8) Hitting Bottom (75%): As the stakes and tension rise, nothing the hero does is enough. To become her best self, the hero must “hit bottom” and experience the burden of holding on to her old ways. She must be knocked down, beaten up, and declared the loser. Not just once but two or three times. Only then can she resolve to remake herself totally, from the inside out.

Now, the hero faces a choice between Undesirable Option A and even more undesirable Option B. Can she find a better Option C? Can she rise above the limitations and contradictions of the two unacceptable options? Either way, there is no going back again. The struggle is unrelenting.

ACT III: RECOGNITION AND RESOLUTION

In the end, the hero experiences success or failure. Either she learns and grows to become her best, most authentic self—or she squanders that opportunity. The hero’s success or failure tells you everything you need to know about her character.

(9) Failure and Brooding (75% to 80%): The hero holds one last pity party at her nadir. She mopes and complains and declares herself the loser. At the same time, she begins to realize that she needs to abandon her limiting beliefs and figure out how to solve her urgent life-or-death problem.

The time for rebuilding has arrived. Emotionally, the hero decides that she has to carry out a final process of transformation. She needs to fight for something that matters.

(10) The Answer! (80%): At last, the hero figures out (or fails to figure out) how to confront her most profound challenges. She has to leave her old life behind to begin a new life. Every gain entails a loss. That’s a hard lesson, but it is also the very essence of maturity, wisdom … and resurrection.

(11) Plan and Execute (80-90%): It’s time to act. The hero has to assemble her posse, make plans, and mount a victorious (or losing) last stand.

(12) The Final Battle (95-98%): Finally, the climax: The hero’s deeper desires and values finally prevail. She takes a less simplistic view of the world, understands it more profoundly, and remakes herself accordingly (or fails to, in a tragedy).

(13) The New Status Quo (99-100%): In the end, we see the hero in her new world, with her new values and wisdom. Metaphorically, she has found the magic elixir (or, in a tragedy, finds herself defeated forever). In this final scene, we get an indication that a new approach might work—no promises. We might want a sequel.

→ Case Study: Alfred Hitchcock’s Rear Window

When the photojournalist L.B. “Jeff” Jeffries breaks a leg on assignment, he finds himself confined to a small apartment in New York, watching his neighbors across the alley. Between visits by his girlfriend Lisa and his physical therapist Stella, he begins to suspect one of his neighbors has murdered his wife.

That’s the setup for Alfred Hitchcock’s classic film Rear Window, which he adapted from Cornell Woolrich’s 1942 short story “It Had to Be Murder.”

ACT I: WORLD OF THE STORY

(1) Establishing Shot (0 to 1%): The story opens a view of the apartments across the alley—a composer, newlyweds, gardeners, a dog-loving couple, a sculptor, and a character dubbed Miss Lonelyhearts. Also across the way is a middle-aged couple; the woman is an invalid who quarrels with her husband. As the camera pans to Jeff and his work as a photographer, we sense he won’t be able to avoid the drama developing across the alley.

(2) Statement of Value (5%): In a phone call with his editor, Jeff expresses irritation that he is missing out on a choice assignment because his leg will be in a cast for another week. A man of adventure, he is itchy for action. (Soon, he’ll get it.)

(3) The Challenge/Catalyst (10%): As Stella gives Jeff his physical therapy, they both sense that “trouble” lies ahead. The summer heat and Jeff’s restlessness are part of it. Something seems awry as Jeff watches his neighbors.

(4) No Going Back (20-25%): The glamorous Lisa comes to treat Jeff to a fancy meal and her lovely attention. They quarrel about their relationship; she wants to get married, but he refuses to give up his life of adventure. Something’s got to give. This story will settle this matter, one way or another.

(5) Hero, Meet Your Life Coach (22%): Lisa and Jeff notice an argument between an unhappy middle-aged couple named Thorwald—a traveling salesman and his invalid wife. As Jeff and Lisa watch the couple, they get bad vibes, accentuated by their unresolved relationship. It’s as if an intruder came into their lives. This moment offers no single life coach, but the activities in other apartments offer a complete survey of the values Jeff must consider throughout the story.

ACT II: RISING ACTION

(6) Success! Or Failure! (25%): Jeff and Lisa’s dinner goes sour. One thing is sure: To remain with Jeff, Lisa must show she’s a woman of adventure and glamor.

(7) Halftime, or Throwing the Hat Over the Wall (50%): Now convinced that his neighbor Thorwald has murdered his wife, Jeff calls a detective friend named Doyle, who agrees to check on the situation. Nurse Stella, meanwhile, tries to track a mysterious trunk that Thorwald has packed and sent away.

(8) Hitting Bottom (75%): Detective Doyle reports that Thorwald has alibis. Mrs. Thorwald, he says, is alive and well. He scolds Jeff and Lisa for concocting a crazy conspiracy theory.

ACT III: RECOGNITION AND REVERSAL

(9) Failure and Brooding (75% to 80%): As Jeff and Lisa scold themselves for their ghoulish obsession with a possible murder—and agree to avoid the topic from now on—the death of a neighbor’s dog raises new suspicions. The dog had been digging in Thorwald’s garden. As the neighbors cry out in distress, all the neighbors come to their windows except Thorwald, who sits in his dark apartment smoking a cigar.

(10) The Answer! (80%): Jeff writes an anonymous note to Thorwald: “What have you done with her?” Lisa delivers it. Thorwald looks surprised and concerned—maybe even guilty when he reads it.

(11) Plan and Execute (80-90%): Jeff calls Thorwald and tells him to meet at a nearby bar to get out of the apartment. With Thorwald gone, Lisa checks the garden where the dog had been digging. Lisa then goes into Thorwald’s apartment, and Thorwald returns and confronts her. Jeff calls the police to rescue Lisa before Thorwald harms her.

(12) The Final Battle (95-98%): After catching Jeff staring at him through the window, Thorwald comes over to confront him. “What do you want?” he asks. After a brief battle—in which Jeff fights off Thorwald by blinding him with camera flashes—Thorwald finally pushes him out the window. Police, meanwhile, get a confession.

(13) The New Status Quo (99-100%): Jeff is homebound again after breaking a second leg. But now Lisa has proven her mettle as a sidekick and a lover. They are last seen quietly enjoying each other’s company.

Rear Window is a perfect story: A tightly focused narrative that uses a drama of a few people’s lives over a few days to explore both interior and expertise questions. Because we care about Jeff and Lisa, we are drawn into their view of the world. That view shows us profound questions about life and death, love and loss, everyday boredom and life-changing adventure.

Your Turn

Using the key story moments, write a short outline of a narrative. Do not try to tell the whole story—only a dozen defining moments. Describe: (1) the establishing shot, when the hero expresses a desire; (2) the statement of a higher value; (3) the challenge or catalyst for the story; (6) the realization that something deeper matters more; (7) the halftime moment when the hero decides to go all in; and (10) the moment when, after failure and brooding, the character discovers the answer.