Somewhere, right now, someone is bemoaning the decline of writing. Grammar scolds lay down the law on the “proper” ways to speak and write. Business executives complain about the poor quality of emails. Government bureaucrats wade through piles of regulatory documents. And teachers grouse that texting and social media make their jobs impossible.

Statistics support the complaints. By one account, American businesses suffer $204 billion in lost productivity every year because of poor writing. Businesses and colleges must run remedial courses on writing. But writing programs—in schools and companies—usually make little difference. Less than half of the 2,300 students tracked in a four-year study said their writing had improved in college.

To the rescue comes Steven Pinker, the rock-star language maven from Harvard. Pinker is celebrated for his friendly and lucid style. The subtext of his writing might be: Here, let me translate what those eggheads are saying—and how you should think about these academic debates.

Pinker seems the perfect candidate to write a definitive writing guide. After writing two scholarly tomes early in his career, he has become a popularizer of intellectual ideas. In The Language Instinct, The Blank Slate, and How the Mind Works, Pinker offers erudite tours of the mysteries of thinking and acting. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, he shows that the world is becoming a safer, less violent place.

Pinker seems the perfect candidate to write a definitive writing guide. After writing two scholarly tomes early in his career, he has become a popularizer of intellectual ideas. In The Language Instinct, The Blank Slate, and How the Mind Works, Pinker offers erudite tours of the mysteries of thinking and acting. In The Better Angels of Our Nature, he shows that the world is becoming a safer, less violent place.

Alas, Pinker fails. His guide The Sense of Style is a mess. He does a decent job explaining “classic style,” in which the writer “orients the reader’s gaze,” pointing out interesting or important things in a conversational style. But he gets lost in a maze of academic exercises and random prescriptions. For 62 pages Pinker expounds on abstract models for analyzing writing. For 117 pages, he renders judgment on a random assortment of quarrels on word usage. Very seldom does Pinker actually explain how to write well, sentence by sentence and paragraph by paragraph.

The manual we need

A good writing manual would begin with the two essential elements of writing: the sentence and the paragraph. Hemingway once noted that “one true sentence” was the foundation of all good writing. The good news is that anyone, with the right basic skills, can write that one true sentence—and then a second, a third, and so on.

So where is Pinker’s advice on composing a sentence? Nowhere and everywhere. Pinker jumps from topic to topic—from the minutiae of grammar to disagreements over word meanings—but he never shows how to craft good sentences for all occasions. When he explores the way sentences get tangled, the dazzled/befuddled reader has no real foundation for the discussion. It’s as if someone described the infield fly rule in baseball without first explaining that pitchers throw, hitters swing, and fielders catch.

Maybe Pinker finds the basics too, well, basic. Maybe he doesn’t want to dwell on the simple subject-verb-object structure because, well, it’s just so obvious. But until we master these basics, we can’t understand more complicated structures—how to build complex and complicated sentences, how modifiers work, how to identify subjects, how to connect ideas, and when to break rules. Since we lack that basic point of reference, Pinker’s more esoteric explorations often get lost in the shuffle.

What about paragraphs? Forget it. “Many writing guides provide detailed instructions on how to build a paragraph,” Pinker says. “But the instructions are misguided, because there is no such thing as a paragraph.” It’s true that the paragraph offers “a visual bookmark that allows the reader to pause.” It’s also true, if you want to understand writing with Pinker’s tree analogy, that paragraph breaks “generally coincide with the divisions between branches in the discourse tree.”

But that’s a copout. We can do better. Try this working definition: A paragraph is a statement and development of a single idea.

All too often, when we first begin writing a passage, as Pinker notes, our thoughts spill out, one after another. We begin with one thought and then, without developing it, jump to another thought. And so paragraphs become jumbles of thoughts, some developed and some not. After a while, we hit the return key. We think we have written a paragraph just because we have created, as Pinker says, a brief pause.

To avoid catch-all paragraphs, you should be able to identify the ONE idea that you’re developing in that paragraph. To make sure you express and develop just one idea in each paragraph, label each idea. If a paragraph contains two ideas, break it up in to two paragraphs—or get rid of the extra idea if it’s not germane to the piece.

Most strong writers over the past century—Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Eudora Welty, Gay Talese, Elizabeth Gilbert, Laura Hillenbrand—follow the one-idea rule. Each paragraph is a mini-essay, a complete expression of an idea, which follows the previous idea and sets up the next.

Complicating matters

How does Pinker fail so badly? Quite simply, he falls victim to the “curse of knowledge,” which he describes in the book’s second chapter. Immersed for decades in academic writings on neurology, evolution, and linguistics, Pinker takes simple questions and turns them into complex academic discourses. Few if any writers—students, business people, journalists, or even academics—will get clear direction from Pinker about turning their muddy writing into clear, vivid prose.

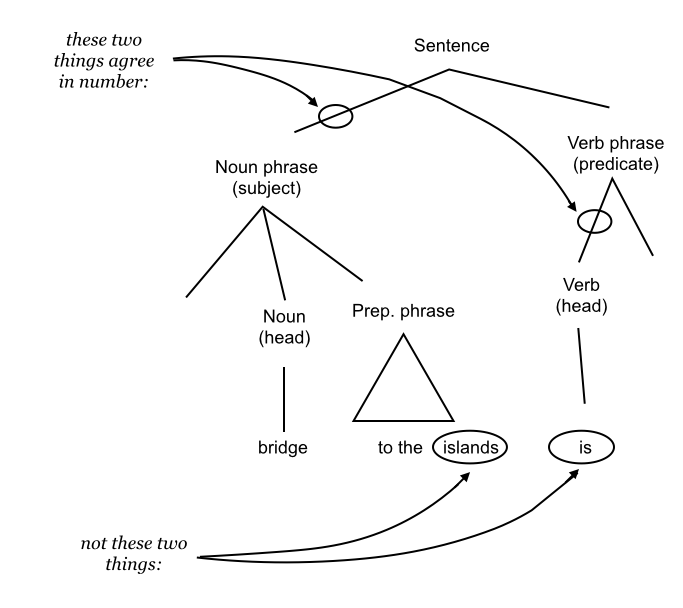

Consider the following sentence: “The bridge to the islands are crowded.” Can you spot the error? It’s simple, really. Since “bridge” is the subject, the verb should be the singular “is,” not the plural “are.” Alas, since the verb follows “the islands,” too many writers make the verb plural.

How does Pinker analyze this sentence? He sees it as a tree, with various branches and branches of branches. To analyze the sentence, he offers a diagram that looks like strands of spaghetti (some cooked, some raw) thrown together. It’s a sight to behold: curved and straight lines, arrows, ovals, a triangle, with some (but not all) of the words in the sentence under study.

I’ve shown the image to friends and colleagues and they shake their heads. “Above my pay grade,” one said.

As a linguistic play structure, I suppose, Pinker’s tree diagrams might offer some amusement. But must we make matters so complicated?

Here’s an easier way. Find the subject and verb. Put brackets around modifying phrases (usually prepositional phrases). Therefore:

The bridge [to the islands] is crowded.

By bracketing the subject’s modifier—the prepositional phrase “to the islands”—you can see the core structure: “The bridge is crowded.”

Let’s take another example—Pinker’s concept of “the gap.” Look at the following sentence:

The impact, which theories of economics predict are bound to be felt sooner or later, could be enormous.

To get this passage right, Pinker suggests inserting a “gap” into the middle of the sentence, like this:

The impact, which theories of economics predict ____ are bound to be felt sooner or later, could be enormous.

Huh? This makes my hair hurt. Rather than focusing on simple structures, Pinker begins with complicated structures. Then he constructs a complicated user’s manual to examine them. Hello, Ikea.

Strangely, Pinker never offers a step-by-step process for writing from scratch. In this book, the only real instruction he offers is in rewriting awkward passages. When he rewrites, he usually maintains the basic structure of the passage. But why? So often, two shorter sentences work better than one long sentence. But Pinker pays no attention. He wants to play with something complex, not create something new by starting simply.

Confusing organization

Perhaps the book’s biggest problem in Pinker’s book comes from his aversion to signposts. A signpost is any device that orients the reader along the way. Think of the signposts you see when driving: GAS/FOOD/MOTEL … JOHNSON CITY, CORPUS CHRISTIE, NORTH ALAMO STREET … LAGUARDIA AIRPORT. These signs indicate, clearly and without any fuss, just where you are on the journey.

We need signposts for writing as well. As cub writers in middle school, we we learn to use the transition: “As we have seen …,” “The second objection …,” “On the other hand …,” “Therefore …,” and so on. In longer pieces, like research papers and books, we use sub-headlines to signal new topics. (Can you see the signposts in this too-long blog post?)

Signposting, ultimately, reveals the basic outline of a piece. Pinker would benefit from such a breakdown. Had he broken chapters into clearer sections and subsections, he would have seen just how rambling his prose can be. And he could have reorganized his thoughts into a logical sequence.

Without these signposts, Pinker skids all over, like a car on ice. In his chapter about “classic style,” for example he jumps from one technique to another: similes, metaphors, showing, analogy, narrative, metadiscourse, signposting, questions, asides, voice, hedging, intensifiers, just to mention a dozen. You need to hunt for these ideas, though. In the end, Pinker’s guide is no guide at all.

To nitpick or not to nitpick?

Pinker seems happiest when sorting the do’s and don’ts of grammar. He is, after all, the chair of the usage panel of the American Heritage Dictionary. He revels in the endless debates about etymology, slang, context, neologisms, and anachronisms.

Pinker amiably dismisses the concerns of Chicken Little stylists. Language, he explains, evolves. We need to adapt old words to new circumstances and invent new expressions. (True, dat.) Pinker scolds the stylists who scold others for using words like “contact.” He also takes on the purists who cling to outdated definitions for words like “decimate,” which people now user to say “destroy most of” (nopt the original meaning “reduce by one tenth”). He dismisses concerns about split infinitives and ending sentences with prepositions. He even comes to the defense of passages like “Me and Amanda went to the mall.” On that last point, Pinker explains that the Cambridge Grammar “allow[s] an accusative pronoun before and.” Of course.

Pinker wants language to breathe, grow, adapt—and sparkle. Good for him. But then, over 117 pages, he acts as the Grand Poobah of Word Usage. Often he provides a cogent explanation; often he doesn’t.

Pinker deems that we can “safely ignore” language purists on the following expressions: aggravate, anticipate, anxious, comprise, convince, crescendo, critique, decimate, due to, Frankenstein, graduate, healthy, hopefully, intrigue, livid, loans, masterful, momentarily, nauseous, presently, raise, transpire, while, and whose.

But for the following expressions, which he calls malapropisms, Pinker rules that we must hold fast to classical meanings: as far as, adverse, appraise, begs the question, bemused, cliché, compendious, credible, criteria, data, appreciate, economy, disinterested, enervate, enormity, flaunt, flounder, fortuitous, fulsome, hone, hot button, in turn, irregardless, ironic, literally, luxuriant, meretricious, mitigate, new age, noisome, nonplussed, opportunism, parameter, phenomena, politically correct, practicable, proscribe, protagonist, refute, reticent, simplistic, starch, tortuous, unexceptionable, untenable, urban legend, and verbal.

All of this is debatable. To decide, I would consider the rule’s logic as well as the expressive goal. I would disagree with Pinker, for example, on anxious. Its longtime meaning is worried and, to me anyway, the word still carries an edgy kind of anticipation. But Pinker and the AHD Usage Panel shrug and accept the growing use of the word to mean eager. I disagree, respectfully. That’s the point: We need to debate these matters as language evolves.

Pinker is proof of his own critique of experts–that they sometimes know so much that they struggle to take the make the simplest and most important points.