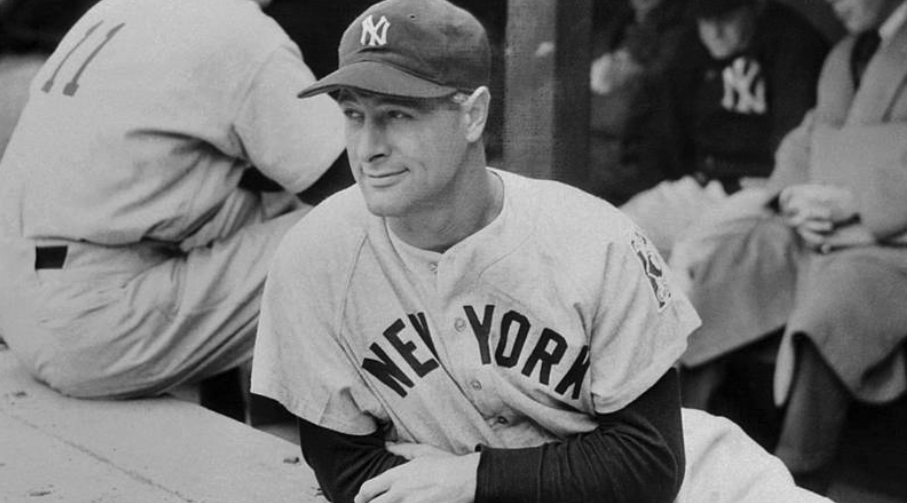

On June 2, 1925, a 21-year-old rookie named Lou Gehrig played first base for the New York Yankees against the Washington Senators. He replaced Wally Pipp, a star player who was struggling with a .244 batting average. Gehrig was hitting only .167 in limited duty, but the Yankees were just a game out of last place and something had to change. That day, in an 8-5 Yankees victory, Gehrig got three hits in five at-bats.

You know the rest of the story. Poor Wally Pipp never returned to his position and ended up getting traded to the Cincinnati Reds. Gehrig, the “Iron Horse,” played in 2,130 consecutive games until he took himself out of the lineup on May 2, 1939. His consecutive-games record stood for 56 years. Cal Ripken broke the record on September 2, 1995 and then extended it to 2,632 games.

You know the rest of the story. Poor Wally Pipp never returned to his position and ended up getting traded to the Cincinnati Reds. Gehrig, the “Iron Horse,” played in 2,130 consecutive games until he took himself out of the lineup on May 2, 1939. His consecutive-games record stood for 56 years. Cal Ripken broke the record on September 2, 1995 and then extended it to 2,632 games.

Why Gehrig benched himself is the stuff of tragedy. After just eight games in 1939, he realized he had no energy or power. He could not control his athlete’s body any more. His teammates had noticed his physical decline for a year but he tried to ignore the signs. On June 19, his 36th birthday, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, later known as Lou Gehrig Disease. He never played again. He died on June 2, 1941, the 16th anniversary of the streak’s first full game (he pinch-hit the day before), at the age of 37.

What most people remember about Gehrig, thanks to Gary Cooper’s portrayal in “The Pride of the Yankees,” is his simple, decent, sweet, uncomplaining, stoic response to this awful disease, which ravaged a once virile man until he could not walk or speak or swallow. In possibly the most iconic moment in baseball history, Gehrig summoned his strength to thank 61,808 fans who gathered at Yankee Stadium for Lou Gehrig Appreciation Day on the Fourth of July in 1939.

“For the past two weeks you have been reading about a bad break,” he told the crowd. “Yet today I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth.” He thanked the team’s owner, general manager, recent managers, teammates, parents, wife, in-laws, groundskeepers, and fans. Then he concluded: “So I close in saying that I might have been given a bad break, but I’ve got an awful lot to live for. Thank you.”

If that scene doesn’t move you, you can’t be moved.

But as baseball honors this man on June 2, a greater tragedy has never been appreciated. By not exploring this greater tragedy, baseball misses the opportunity to honor Lou Gehrig in the most meaningful way.

The Cost of Trauma

The following question cannot be answered with certainty: Did the traumas throughout Lou Gehrig’s life — and his heroic stoic response to those traumas — kill him?

Dr. Gabor Maté, a leading authority on trauma and addiction, argues that 90 percent of all disease originates in trauma. Emotional stress, Maté says, causes terrible strains on the brain, the hormonal apparatus, the nervous system, and the immune system.

Trauma, Maté says, is a “disconnection from ourselves.” Trauma often begins with outside events, like a car crash, the death of a loved one, a debilitating accident, physical or emotional abuse, or a sense of abandonment. When a person experiences an awful event but does not get enough care or love, she represses her feelings. She does so to survive, to get through another day. It’s an emergency response.

Emotional stress overwhelms the physical system. Maté, the author of When the Body Says No, often quotes a 2012 article in the journal Pediatrics. Jack P. Shonkoff of the Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University and his colleagues argue that the repression of trauma creates a series of compensations, making the body susceptible to longterm damage.

Under conditions of extreme disadvantage, short term physiologic and psychological adjustments that are necessary for immediate survival may come at significant cost to lifelong health and development. Indeed, there is extensive evidence that the longterm consequences of deprivation, neglect, or social disruption can create shocks and ripples that affect generations, not only individuals, and have significant impacts that extend beyond national boundaries.

Emotionally, repression can lead people to avoid acknowledging pain, to pretend it’s not there or doesn’t matter. It can cause them to be stoic and uncomplaining — turning the early trauma into ongoing trauma.

Although manageable levels of stress or normative and growth promoting toxic stress in the early years (i.e., the physiologic disruptions precipitated by significant adversity in the absence of adult protection) can damage the developing brain and other organ systems and lead to lifelong problems in learning and social relationships as well as increased susceptibility to illness.

Since Decartes, scientists and medical experts have separated mind and body. The isolation of distinct systems can lead to greater understanding of those parts, as well as treatments for maladies. But the brain is actually inseparable from the body; the brain is as much a part of the body as the digestive tract or the pulmonary system. Damaged brains lead to damaged whole body systems.

A variety of stressors in early life … can cause enduring abnormalities in brain organization and structure as well as endocrine regulatory processes that lead to reduce immune competence and higher or less regulated cortisol levels, among other consequences.

The evidence is jarring. Consider a few examples. A Canadian study found a 50 percent higher cancer rate for people experiencing childhood trauma. An Australian study found a ninefold increase in the risk of developing breast carcinoma among those who suffer trauma. A West Point study found increased likelihood of Epstein-Barr virus for cadets struggling to meet a father’s high expectations. In another study, women struggling with marital problems were found to have diminished immune functioning.

Does this argument put blame on caregivers who might not be able to give adequate care? Gabor Maté says no. He recounts his own experience to make the point. Maté was born in Budapest in 1944 as the Nazis were taking over Hungary. His mother, frightened that they might be killed, gave baby Gabor to a stranger on the street. She hoped to reunite but was determined to save him no matter what happened. Mother and child did reunite but her anxiety, before and after, was intense. As the family learned the full extent of their tragedy — two were killed in camps, others were missing — young Gabor’s whole world was full of anxiety and fear. That created anxiety for the baby. Was it the mother’s “fault” if she could not provide a warm, healing, safe environment under such extreme stress? The very idea is obscene. The point is that we need to make sure everyone, parents and children and their extended circles, gets the support and help they need to deal with this toxic and debilitating stress.

Failing to do this, Maté and other researchers say, has dire consequences. Diseases resulting from trauma include atheroschlerosis, diabetes, Cushing’s disease, Parkinson’s, muscular dystrophy, coronary artery disease, hypertension, stroke, and major depression. Also: ALS.

The Lou Gehrig Story, Take 2

Lou Gehrig suffered trauma from a young age and spent a lifetime quietly compensating for that trauma.

Gehrig was legendary not just for his excellence on the field, but also his willingness to sacrifice for others. He was, by all accounts, a selfless teammate who led by example rather than claiming credit. He played injured for the sake of the team. He guided younger players, protecting them from playing hurt. He gave other stars the spotlight.

Gehrig was the son of German immigrants, an alcoholic father and an overburdened mother. His father Heinrich came to America in 1888 from Adelheim, Germany. He found work sporadically as an ornamental ironworker and sheet metal worker. But he was unreliable, owing to his alcoholism. He spent countless hours at a local tavern. After suffering a debilitating illness, during the time of Lou’s adolescence, Heinrich spent the rest of his life as an invalid. His mother Christina, came to the U.S. in 1899 from Wiltser, Germany. She worked as a maid and a cook to earn most of the family’s annual income of $300 to $400. She was tough but also brittle, unable to address the trauma in her own life.

The Gehrig family lost Lou’s two sisters and brother in childhood. His older sister Anna died at the age of three months. His younger sister Sophie died from a combination of measles, diphtheria, and bronchopneumonia before her second birthday. Lou’s brother died soon after birth and was never named. Lou never spoke about the deaths.

Growing up in poverty, Lou managed as well as he could. Chunky and uncoordinated, he was picked last in pickup games. As he grew into a muscular teen, he was hobbled by a painful shyness, made worse by wearing old clothes and shoes. When he went to school without a coat in winter, he was embarrassed. Like lots of immigrant kids who shared the same fate, he did not complain. He played soccer for three years before he started playing baseball at age 14. He could hit the ball far, which compensated for his shortcomings on the diamond. Eventually, he was good enough to play baseball and football at Columbia University.

Gehrig took a $1,500 bonus to leave Columbia to play for the Yankees to tide the family over until his mother could recover from illness and get back to work. “There’s no getting away from it, a fellow has to eat,” he later told The New York Times. “At the end of my sophomore year my father was taken ill and we had to have money. … There was nothing for me to do but sign up.”

After playing 13 games in 1923 and 10 in 1924, Gehrig got his break with Pipp’s slump in 1925.

He became the steady force on the greatest dynasty in baseball history. Over 14 full seasons, Gehrig batted .340 with 493 home runs. For 13 straight seasons, he scored and batted in at least 100 runs. He led the league in runs four times, home runs three times, RBIs five times, on-base percentage five times, and batting average once. And, of course, he played in 2,130 consecutive games.

The Ongoing Tragedy

Baseball’s greatest tandem was Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. The Dionysian Ruth was as different as could be from the Apollonian Gehrig. But the two happily supported each other in their roles and even socialized together. Ruth was a favorite of Lou’s mother Christina, who fed him her German food and idolized him. But the two stars grew to resent each other. Their fallout began when Christina made a clumsy criticism of Ruth’s wife. Ruth cut off Gehrig. Then in 1937, two years after his retirement, Ruth questioned Gehrig’s commitment to the streak:

I think Lou’s making one of the worst mistakes a ballplayer can make by trying to keep up that “iron man” stuff… He’s already cut three years off his baseball life with it… He oughta learn to sit on the bench and rest… They’re not going to pay off on how many games he’s played in a row… The next two years will tell Gehrig’s fate. When his legs go, they’ll go in a hurry. The average ball fan doesn’t realize the effect a single charley horse can have on your legs. If Lou stays out here every day and never rests his legs, one bad charley horse may start him downhill.

Ruth was right. But for Gehrig to stop, he would have had to abandon a moral code forged in trauma.

Gehrig’s streak subjected his body to constant punishment. While he protected young teammates from playing with injuries, Gehrig insisted on playing with dozens of injuries (including traumatic injuries) his whole career.

As researchers have struggled to understand the specific causes of ALS, they have focused in recent years on traumatic head injuries. God knows how many blows to the head Gehrig suffered playing college football and batting in the era before helmets. Consider this moment: On June 29, 1934, in an exhibition game in Norfolk, Va., he was beaned on his right temple and lay unconscious for five minutes before the team trainer revived him and sent him to a hospital. Gehrig was quoted in the next day’s New York Times: “I have a slight headache and there is a slight swelling on my head where the ball hit but I feel all right otherwise and will be in there tomorrow.” Sure enough, he hit three triples the next day against the Senators before the game was called for rain.

Other injuries were debilitating too: broken bones and backaches and pulled hamstrings, headaches and colds and viruses and the flu. Later X-Rays showed at least eight broken bones on his hands.

Around the time when Cal Ripken broke his record, Gehrig’s former teammate Bill Werber remembered a few of those incidents. After breaking the middle finger of his glove hand, he barely waved his bat. “He’d hit with part of his hand literally off the bat,” Werber said. “Don’t ask me how.” When Gehrig’s foot was spiked in a play at first base, Werber said, “he hurt terribly.” But he kept playing. By playing, he probably contributed to his untimely demise.

Baseball fans celebrate the Iron Horse for his selfless sacrifice. The Los Angeles Times rhapsodized that “there was an essence of nobility, courage and resolve to it. For a country that was enduring a crushing Depression, Gehrig’s record seemed a uniquely American achievement.”

But what if the streak sends exactly the wrong message? What if this individualist model of suffering in silence not only claimed Gehrig’s life but has also harmed generations of American children and families?

Gehrig’s stoic bearing is celebrated, in large part, because it exemplifies the ethos of American individualism. According to this ethos, we should all work hard, take our hits, stifle our hurts, not complain, and tough it out. Americans celebrate toughness and dismiss or even demean those who suffer. In dismissing victims, this ethos has contributed to countless cases (many millions, for sure) of people denying their own pain and not getting the help they needed.

This is, of course, not Gehrig’s fault. He was a victim of this stoicism too. But as we commemorate this man’s life, feats, and spirit, let’s think hard about creating a greater legacy for him and others who have struggled with trauma.