Everyone knows about the Type A personality — the driven, impatient, narrowly focused, executive with a bad temper and high blood pressure.

How this personality type was discovered in the 1950s offers a good lesson for writers about paying attention to details. More about that in a few moments.

How this personality type was discovered in the 1950s offers a good lesson for writers about paying attention to details. More about that in a few moments.

In Elements of Writing seminars, we talk about the importance of the setting for the story. The setting — what I call “the world of the story” — doesn’t just hold the story. It doesn’t just provide a place for characters to pursue their passions and goals. It plays a kind of character as well. The world of the story establishes possibilities and constraints, just like all the other characters. It establishes values. It shapes what matters to the characters.

To understand the world of the story, I think of Fenway Park in Boston. Say what you will about other great ballparks and stadiums. Rave, if you will, about the newer venues like Camden Yards and CitiField and Turner Field and Miller Park. They’re all terrific. But Fenway Park changes things. It expresses values. When I lived in Boston, I went to a dozen games a season, in good years and bad. My favorite moments came when the Sox were down by three runs in the ninth inning in a game that didn’t matter. The place came alive. Everyone stood and chanted. If the Sox got a baserunner, forget it. The place rocked. It was like seventh game of the World Series in a meaningless game in June.

But all that’s obvious, right? After all Fenway has sold out for 712 straight games, going back to May 15, 2003, when Pedro Martinez faced the Texas Rangers. That’s more than 250 games better than the next best streak in baseball history. Fenway’s appeal is common knowledge. Just read John Updike’s paean from 1960.

To earn your chops as a writer, notice the things that no one else does.

Now, back to the story of the discovery of the Type A personality.

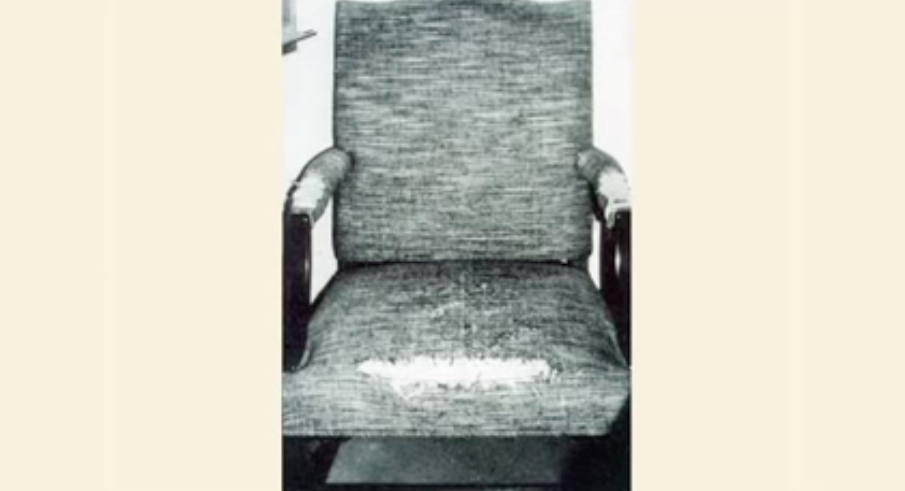

In this account, it was a chair upholsterer who first noticed that a cardiologist’s patients were killing themselves with anxiety. Watch how Robert M. Sapolsky, a professor of biology and neurology at Stanford University, explains the discovery:

When you create the world of your story, find the chair that reveals an important idea. Find the piece of furniture — of the book, piece of art, toy, tshotshke, piece of clothing, window dressing, dish or glass, or other artifact — that helps the reader understand the world of the story.

When I taught essay writing at Yale, students write a different type of essay every other week — profile, action, memoir, idea, parody, review. One of the essays was a complete story about an artifact. It produced some of the best work. Students worked hard to find meaning in objects that could easily be ignored.

Find that artifact that matters. Find the chair roughed up by Type A personalities.