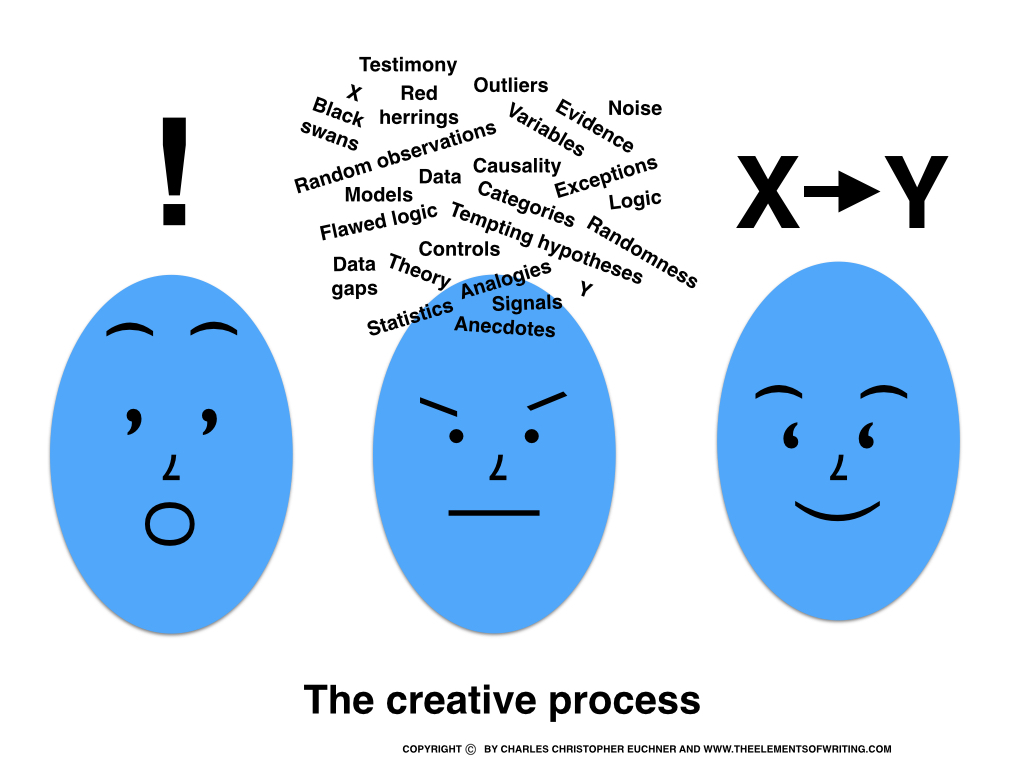

How does creativity happen? Is it, as some would say, a mystical process somehow connected to muses and gods? Or is it a process of grinding, getting up every day and working on the pieces so you can eventually put those pieces into a meaningful whole?

This is, of course, a false dichotomy. It’s not a matter of either/or. It’s both. So we need to understand how the mystical and the grinding come together.

This is, of course, a false dichotomy. It’s not a matter of either/or. It’s both. So we need to understand how the mystical and the grinding come together.

One hint comes from something Linda Ronstadt said long ago: “In committing to artistic growth, you have to refine your skills to support your instincts.”

Or, to quote Louis Pasteur, “chance favors the prepared mind.”

1. Decide on a Plan

To build anything — a bridge, a treehouse, a casserole, a story — you need the right materials and the right skills. It takes a long time to develop the skills. The noted psychologist Anders Ericsson calculates that it takes 10,000 hours of focused, intent work to achieve mastery over a skill. It’s not just practice, practice, practice. It’s practice intently, practice open-heartedly, practice curiously.

I once met a banker named Stanley Lowe who was active in inner-city neighborhood revitalization and historic preservation. For Lowe, good intentions were never enough. Whenever do-gooders offered an idea for a project, he would challenge them: “What’s the plan?”

Without a plan, you don’t have much.

Writing well requires a vast trove of skills. Writers need to master the basic elements of the craft — sentences and paragraphs, grammar, punctuation, quoting, asking good questions, breaking down evidence, finding the right words, observing, sequencing ideas and images, zig-zagging back and forth from scene to summary, and much more.

Anyone can write reasonably well if they can write a great sentence. Nothing matters more than the sentence, as Ernest Hemingway explains in A Moveable Feast:

Sometimes when I was starting a new story and I could not get it going, … I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, “Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.” So finally I would write one true sentence, and then go on from there. It was easy then because there was always one true sentence that I knew or had seen or had heard someone say.

Contrary to mystics who say that writing is a gift from the gods, bestowed on a lucky few, writing can be taught. I can spend an hour with anyone and show them how to write better and faster, right away. I can show anyone how to write “one true sentence” … and then another and another. After that, it’s up to you.

For you to master this and other skills, you must practice intently, as Ericsson says. You must practice in all kinds of contexts, with all kinds of subjects. You must practice with an open mind. You must realize that everything you write needs revision and editing. You must not be discouraged, but instead more determined, by that basic reality.

So burn all the necessary writing skills into your brain. I have identified 81 specific “elements” of writing. That’s my list. Yours might be 97 or 42. Whatever. You can master a whole raft of techniques and apply them to all kinds of challenges.

You can and must, as Ronstadt says, refine your skills. Or, as Pasteur says, prepare your mind.

Then what?

This is when it gets interesting.

2. Let Go

Now it’s play time. Now it’s time to let your imagination, your subconscious, direct you. In this process, mind and soul blend together. Here’s how William Faulkner’s mindsoul worked:

It begins with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.

Passages like this encourage the mystic’s point of view, that writing is a gift of the gods proffered to a lucky few. But if you know anything about Faulkner or any other great writers (or even just good writers), you know that they work hard. They get up every morning and grind. When they want to quit, they don’t. When they experience writer’s block, they step away, like Hemingway, and reframe their problem.

But when you’ve done the hard work and struggled, mystical stuff does happen. And there’s even a process for that. Here’s how George Saunders describes the process:

A guy (Stan) constructs a model railroad town in his basement. Stan acquires a small hobo, places him under a plastic railroad bridge, near that fake campfire, then notices he’s arranged his hobo into a certain posture – the hobo seems to be gazing back at the town. Why is he looking over there? At that little blue Victorian house? Stan notes a plastic woman in the window, then turns her a little, so she’s gazing out. Over at the railroad bridge, actually. Huh. Suddenly, Stan has made a love story. Oh, why can’t they be together? If only “Little Jack” would just go home. To his wife. To Linda.

What did Stan (the artist) just do? Well, first, surveying his little domain, he noticed which way his hobo was looking. Then he chose to change that little universe, by turning the plastic woman. Now, Stan didn’t exactly decide to turn her. It might be more accurate to say that it occurred to him to do so; in a split-second, with no accompanying language, except maybe a very quiet internal “Yes.”

He just liked it better that way, for reasons he couldn’t articulate, and before he’d had the time or inclination to articulate them.

Once the process of creation begins, it exerts its own power. The deeper you get into a story, the more detailed you must be. Every detail does two things. First, it makes everything more real and compelling. No one (except ideologues) gets excited about generalities. But everyone can get intrigued by real, flesh-and-blood characters. The more specific a situation, the greater its universal appeal.

Second, detail closes down some avenues while opening others. As we learn new details about the hobo, we open ourselves to new possibilities. Maybe the hobo had a relationship with the object of his eye, or someone like her. Maybe he once occupied a comfortable house, too. Maybe he has a whole world, far from the bridge, that he longs to recover. Every detail opens new possibilities. But it also closes possibilities. If the hobo remembers an old flame when he eyes the woman, other story lines fade away. He that woman is the image of an old love, then she is not the image of an old nemesis or landlady or teacher or boss or prosecutor.

Creation, as Faulkner says, begins to move of its own accord. The creator cannot plan everything at the beginning of the process. The creator can set the parameters of the story — it will take place at a certain time and place, with a certain set of characters, with a certain destination — but then allow the process of discovery to play a big role in moving the narrative forward.

3. Make Tweaks and Adjustments

Once the story takes off, it’s tweaking time. Hemingway said to “write with your heart, edit with your head.” Get stuff down on the page, then fiddle with it.

Again, George Saunders explains:

What does an artist do, mostly? She tweaks that which she’s already done. There are those moments when we sit before a blank page, but mostly we’re adjusting that which is already there. The writer revises, the painter touches up, the director edits, the musician overdubs. I write, “Jane came into the room and sat down on the blue couch,” read that, wince, cross out “came into the room” and “down” and “blue” (Why does she have to come into the room? Can someone sit UP on a couch? Why do we care if it’s blue?) and the sentence becomes “Jane sat on the couch – ” and suddenly, it’s better (Hemingwayesque, even!), although … why is it meaningful for Jane to sit on a couch? Do we really need that? And soon we have arrived, simply, at “Jane”, which at least doesn’t suck, and has the virtue of brevity.

But why did I make those changes? On what basis?

On the basis that, if it’s better this new way for me, over here, now, it will be better for you, later, over there, when you read it. When I pull on this rope here, you lurch forward over there.

It’s not just intuition, of course. A good writer has a process for tweaking and editing. I call my method “Search and Destroy.” Deliberately, I search for certain kinds of problems — weak starts or finishes, too many bully words (adjectives and adverbs), unclear images, muddled explanations, and so on — and then try to fix them.

As I look for problems in this way, new ideas occur to me. I need a different detail. What if I juxtaposed these characters/ideas? How can I fix this phrasing? Sometimes, addressing these issues opens the whole process up again. Sometimes I scrap whole sections or revamp them, with whole new approaches.

4. Bear Down and Let Go: One Strategy

In my seminars on storytelling, students learn how to both plan and let go. One of my favorite exercises is the Character Dossier. I give students a list of questions about the character. Step by step, we create a character from whole cloth. Every answer defines the character a little more. Every answer provides more detail, opening some possibilities and closing others. If you say a character was born in Moline, Illinois, in 1963, she cannot be a hipster millennial in Brooklyn in 2017. If she lost her parents in a plane crash when she was 12, she can’t deepen her relationship with them when she’s 40.

When we fill in the Character Dossier, we write much of the story. When we know enough about characters to set them into motion, they take over the story. That’s what Faulkner was talking about. Before the characters can lead us, we have to prepare them.

When we have a complete command of all the skills of writing — and when we have set up the model town, as Saunders describes it — we can let go. After we let our characters loose, we need to intervene again to give some kind of order to all the character sketches and scenes and details.

So, you see, creativity is a process of bearing down, then letting go … then bearing down again. Bear down, then let go, again and again. Lather, rinse, repeat.

Image by John Hain.

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.