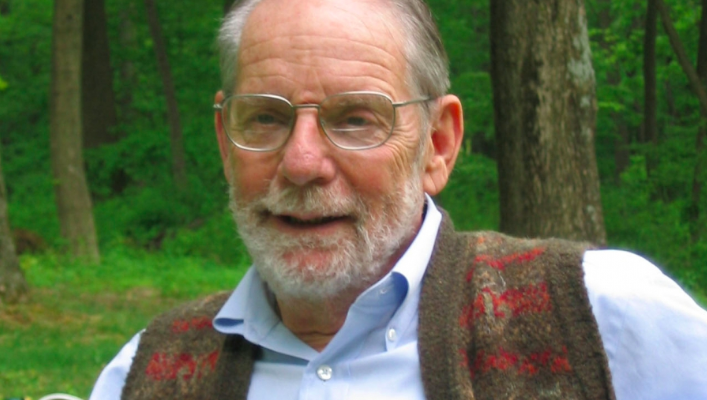

No one in our time has contributed more to nonfiction narrative–stories that are true–than John McPhee. And he has lessons to teach.

McPhee is the writer for The New Yorker and creative writing professor at Princeton University. His books include the Pulitzer-Prize winning Annals of the Former World (a trilogy on geology and geologists), A Sense of Where You Are (about Bill Bradley as a basketball star at Princeton), Levels of the Game (about a classic tennis match between Arthur Ash and Clark Graebler), The Pine Barrens (about the forests of central New Jersey), Encounters with the Archdruid (about three wilderness areas), The Survival of the Bark Canoe (about a New Hampshire craftsman), The Control of Nature (three stories about man’s battle with the natural world), Uncommon Carriers (about water freight), and many more.

McPhee is the writer for The New Yorker and creative writing professor at Princeton University. His books include the Pulitzer-Prize winning Annals of the Former World (a trilogy on geology and geologists), A Sense of Where You Are (about Bill Bradley as a basketball star at Princeton), Levels of the Game (about a classic tennis match between Arthur Ash and Clark Graebler), The Pine Barrens (about the forests of central New Jersey), Encounters with the Archdruid (about three wilderness areas), The Survival of the Bark Canoe (about a New Hampshire craftsman), The Control of Nature (three stories about man’s battle with the natural world), Uncommon Carriers (about water freight), and many more.

His students include David Remnick (Pulitzer Prize-winning author and editor of The New Yorker), Richard Stengel (managing editor of Time), Robert Wright (author of The Moral Animal and other works), Eric Schlosser (author of Fast Food Nation and other books), Richard Preston (author of The Hot Zone), Tim Ferriss (best-selling author and self-hacking guru), Jennifer Weiner (author of Good In Bed and other novels), and many more.

So McPhee knows writing. And, lucky for us, he lays out his techniques in Draft No. 4, part memoir and part writing manual. here are some of the highlights:

1. Selecting and Framing Topics

At the beginning of Draft No. 4, McPhee describes his random way of selecting topics. After years of writing straight profiles for Time and The New Yorker, McPhee decided to profile two people. “Then who?” he asked himself. “What two people?” He considered various pairs who had to work together to achieve their own aims–the actor and director, the architect and client, the dancer and choreographer, the pitcher and manager. Then, randomly, he watched a 1968 semifinal match of the U.S. Open. Something about the players–Arthur Ashe and Clark Grabner–intrigued him. So he pursued it. The result was Levels of the Game, which became the model for analytic sportswriting.

With a dual portrait in the bag, McPhee decided to create a portrait of four people. But how do you organize a fourplex portrait? McPhee decided to identify one main character and show how that character interacts with three others. The lead character, first among equals, would give the piece a unity; the three other characters would reveal a wider range of perspectives and personalities. McPhee pictured his scheme like this:

ABC

D

McPhee decided to write something about the emerging environmental movement. Before finding Characters A, B, and C, he had to find Character D. After casting around for an Aldo Leopold type, he discovered David Brower of the Sierra Club. Now, who could be Dominy’s antagonist? Soon enough he found Floyd Dominy, the U.S. commissioner of reclamation, who had clashed repeatedly with Brower. “I can’t talk to Brower because he’s so goddamned ridiculous,” Dominy told McPhee. So, McPhee said, would you be willing to get on a rubber raft going down the Colorado River with him? “Hell, yes!” Dominy said. With those two characters lined up, McPhee went in search of two more.

Once McPhee finished that piece, which became Encounters With the Archdruid, he continued his quest for more complex portrait structures. “So, at the risk of getting into an exponential pathology,” McPhee writes, “I started to think of a sequence of six profiles in which a seventh party would appear in a minor way in the first, appear in a greater way in the second,” and so on.

McPhee has lots of interests–the environment, sports, politics, technology, the labor process–but they followed his desire to master various structures of writing. He decided how to write before he decided what to write about. Which, of course, is completely backward.

Or is it? As McPhee notes, “The Raven” originated not in Edgar Alan Poe’s fascination with a man’s suffering over lost love but, rather, Poe’s desire to use a one-word refrain with a long “o” sound. So the origin of the poem was the famous refrain: “Nevermore.” With that word in place, Poe had to figure out who would say “Nevermore,” over and over. For that role he selected a raven, speaking to the distraught man.

Alfred Hitchcock did something similar. When brainstorming a film, he identified places he wanted to shoot. So he decided to shoot a scene at the face of Mount Rushmore. After that location, he decided to use a vast farm as a scene. With those and other scenes in his lineup, he had to decide what would happen there. The result, eventually, was the film North By Northwest. Another time, he decided he wanted to shoot scenes at a London chapel and at the Royal Albert Hall. Those scenes eventually played leading roles, if you will, in The Man Who Knew Too Much. “Of course, this is quite the wrong thing to do,” Hitchcock said. Maybe, maybe not. But he did it and it worked.

Whatever the process, the writer starts with a blank slate. The possibilities are as broad as the writer’s imagination and ability to explore. But once he makes a fateful decision–once he picks this structure instead of that structure, this scene instead of that scene, this character instead of that character–the possibilities narrow. Every decision not only excludes certain possibilities, it also increases the likelihood of others.

2. Narrowing Ideas

That’s when things get interesting. Once McPhee picked Floyd Dominy for his four-person portrait, he had to seek out the ideas, events, characters, and conflicts that would make it work. Every decision narrowed his scope. Every decision drove McPhee toward more and more specific topics. Before long he was on that Colorado River with his four main characters, discovering what their time together, on the river, revealed about their character and their causes.

Now we are in the heart of the writing process, which mostly happens before the author has written a single word–research. The author must go out and gather as much information as possible. Inevitably, he will gather far more than he can ever consider using–ten times more, at least. Out of all that information, the author will begin to understand his subject. He will begin to convey impressions about who, what, when, where, and why. Paraphrasing Cary Grant, McPhee tells his students that “a thousand details add up to one impression.”

The author makes countless decisions about what to consider and what to ignore. More-or-less random decisions (focusing on one character or two or four or six characters) give way to decisions about specific people, things, places, events, and ideas. The author is always asking himself: This or that? And: Then what? The materials start to fill notebooks, audio files, picture files. The process develops momentum. Faulkner once said:

It begins with a character, usually, and once he stands up on his feet and begins to move, all I can do is trot along behind him with a paper and pencil trying to keep up long enough to put down what he says and does.

Faulkner was working from his imagination. Nonfiction writers like McPhee draw from their piles of notes. Once they have enough material, they start, like Faulkner, to chase their characters and putting them into actual scenes, summaries, descriptions, and analyses.

3. Research and Interviewing

Before you write a word, you need to gather information, from books and websites, observation and interviewing, daydreaming and structured brainstorming. Then you sort and select.

Research involves not only library/Internet research, but also getting out into the field to observe the real world. That process raises the anthropologist’s dilemma. When you show up to observe people, your presence can affect people’s behavior:

As you scribble away, the interviewee is, of course, watching you. Now, unaccountably, you slow down, and even stop writing, while the interviewee goes on talking. The interviewee becomes nervous, tries harder, and spells out the secrets of the secret life, or maybe just a clearer and more quotable version of what was said before. Conversely, if the interviewee is saying nothing of interest, you can pretend to be writing, just to keep the enterprise moving forward.

Never worry about looking smart to the interviewee. What matters is getting information, not looking good. “Who is going to care if you seem dumber than a cardboard box?” McPhee asks.

4. Getting Words on Paper

Everyone, at one time or another, faces the dread of an empty screen with no ideas. McPhee offers a familiar solution: Forget you’re a writer and pretend you’re just an ordinary person trying to explain a topic to a friend or loved one.

For six, seven, 10 hours no words have been forthcoming. You are blocked, frustrated, in despair. You are nowhere. … What do you do? You write, ‘Dear Mother.’ And then you tell your mother about that block, the frustration, the ineptitude, the despair. You insist that you were not cut out to do this kind of work. You whine, you whimper, you outline your problem, and you mentioned that the bear has 55-inch waist and a neck more than 30 inches around but could run nose to nose with Secretariat. You say the bear prefers to lie down and rest. The bear rest 14 hours a day. And you go on like that as long as you can. And then you go back and delete the ‘Dear Mother’ and all the whimpering and whining and just keep the bear.

Start, then, by venting. Forget about what you want to say. You explain what you would write about if you could. In that process, the words start to flow. The words are not perfect, mind you. But you manage to get words on paper. “Just stay at it,” McPhee says. “Perseverance will change things.”

The trick is to melt the frozen mind. If you have done the research, you have surely something to say. If you’re scared, for whatever reason, your knowledge and insights are out of reach — but they’re never too far below the surface. You can coax them to the surface, sooner or later.

“The mind is working all the time,” McPhee says. “You may actually be writing only two or three hours a day, but your mind, in one way or another, is working on it 24 hours a day – yes, while you sleep – but only if some sort of draft or earlier version already exists. Until this exists, writing has not really begun.”

To write even a short piece — say, 1,200 to 1,500 words, the length of a typical college paper — requires hundreds of choices, as McPhee notes:

Just to start a piece of writing you have to choose one word and only one from more than 1 million in the language. Now keep going. What is your next word? Your next sentence, paragraph, section, chapter? Your next ball of fact. You select what goes in and you decide what stays out. At base you have only one criterion: if something interests you, it goes – if not, it stays out. That’s a crude way to assess things, but it’s all you got.

Whatever you do, get something down on paper. Don’t even think of judging whether it’s good or not.

How could anyone ever know that something is good before it exists? And unless you can identify what is not succeeding– unless you can see those dark hunky spots that are giving you such a low opinion of your pros as it develops– how are you going to be able to tone it up and make it work?

So spill whatever you know onto a sheet of paper. Once you have words on paper, then you can sort it and decide what deserves to stay.

So: Research, blurt, sort, delete, shift. Rinse, repeat.![]()

5. Start Strong, Finish Strong

Once you begin composing your piece, the most important pieces are the start (known in journalism as “the lead” or “lede”) and the finish.

“The lead, like the title, should be a flashlight that shines down into the story,” McPhee says. “A lead is a promise. It promises that the piece of writing is going to be like this. If it is not going to be so, don’t use the lead.”

The right lead hints at everything, directly or indirectly–not just substance, but style too. Reading the lead is like meeting your tour guide for the first time. She tells you about the trip ahead–what sites you’ll visit, how much information she will offer, what kinds of stories she’ll tell, and, in general, what kind of company she will provide along the way.

The finish might be even more important. It’s your destination. Ideally, it should respond to the question or issue that the lead raises. The finish should feel like the end of a trip. You’ve arrived and you now know much more that you knew at the beginning. Issues that once puzzled you now make sense. Characters who once seemed incomplete are now complete.

In a sense, the lead and the conclusion are always talking to each other as the story or essay proceeds. This dialogue helps you to make decisions for the middle pieces. You can’t talk about just anything and everything anymore. You talk only about what it takes to get from the beginning to the end.

6. Making Comparisons

All communication involves comparing one thing with another, different thing. To learn about a new topic — a simple fact, a concept, a feeling — we need to relate it to something else.

John McPhee’s mastery of the metaphor and simile might seem a stylistic flourish. To be sure, his greatest talents involve his ravenous gathering of facts and insights and his ability to find just the right form to lay out these facts and insights.

But McPhee’s ability to create fresh metaphors and similes reveals–and enables–his sparkling mind. If he spoke in flat and familiar cliches, his thinking would be dull and orthodox. This drabness would be an undertow, pulling down even his best findings.

One of the great joys of Draft No. 4 is the richness of McPhee’s metaphors and similes. A few examples:

• In describing his fascination with oranges, how they’re grown and marketed and the kinds of cultures they support, McPhee describes a habit he picked up whenever his travels took him to Penn Station: “There was a machine in Pennsylvania Station that cut and squeezed them. I stopped there as routinely as an animal at a salt lick.”

• Describing his desire to find the right word, he writes: “At best, thesauruses are mere rest stops in the search for the mot juste. Your destination is the dictionary.”

• On the organizing information into the right structure for a piece: It’s “like returning from a grocery store with materials you intend to cook for dinner. You set them out on the kitchen counter, and what’s there is what you deal with, and all you deal with.”

• To describe a coal train, McPhee guessed at an analogy: “The releasing of the air brakes began at the two ends, and moved toward the middle. The train’s very long integral air tube was like the air sack of American eel.” Once McPhee was satisfied with the metaphor’s aptness, he and his fact checkers had to figure out whether it was accurate. It was.

Metaphors and similes require broad knowledge. Who but McPhee, with his broad understanding of nature, could have come up with the simile of an eel’s air sack? Good comparisons require hard work. They do not just burst into your consciousness, like Kramer at Seinfeld’s door. Which reminds me …

Because they speak to what the reader already knows, metaphors and similes can date themselves quickly. When we use pop culture to evoke an idea, the insight lasts only as long as the pop-cult idea’s currency. A reference to the Jay Z or Kelly Clarkson or Rosie O’Donnell will be meaningless in a year or even a month. Still, if a pop culture reference captures an idea perfectly, use it. Just be sure to explain the image–quickly–so unknowing readers get the reference. (That, of course, can be like explaining a joke. As E.B. White noted: “Explaining a joke is like dissecting a frog. You understand it better but the frog dies in the process.”)

Still, McPhee lauds his New Yorker colleague Robert Wright for his use of an old cultural reference — the image on the Quaker Oats box — to describe the scientist Robert Boulding:

As it turns out, there is a certain resemblance. Both men have shoulder-length, snow white hair, blue eyes, and ruddy cheeks, and both have fundamentally sunny disposition, smiling much or all of the time, respectively. There are differences, to be sure. Boulding’s hair is not as cottony as the Oats Quaker’s, and it falls less down and more back, skirting the tops of his ears along the way.

Should Wright have used the Quaker Oats man? You could make a good case both ways. Anyway, if you use a time- or place-specific comparison, add a quick explanation, as Wright does with the Quaker Oats example.

7. Checking Facts

John McPhee is lucky in ways that most writers can never imagine. Like other New Yorker writers, he benefits from an army of fact-checkers. They sift his drafts, like gold panners, to find errors in his work. Often, McPhee will leave it to the fact checkers to find the facts. He uses notations like these to alert fact checkers of gaps in the draft:

WHAT CITY, $000,000, name TK, number TK, Koming.

In this case, Koming for what’s “coming” or TK for what’s “to come.” These notations, as McPhee explains, “are forms of a promissory note and a checker is expected to pay.”

The imperative to catch errors, McPhee argues, is existential. “An error is everlasting,” McPhee says. “Once an error gets into print it will live on and on in libraries carefully catalogues, scrupulously indexed … silicon-chipped, deceiving researcher after researcher down through the ages, all of whom make new errors on the strength of the original errors, and so on and on into an exponential explosion of errata.”

Errors can get embedded into the most innocent of constructions. McPhee writes: “The commas … were not just commas; they were facts, neither more nor less factual than the kegs of Bud or the color of Santa’s suit.”

Errors are like rats. Even the most aggressive efforts to exterminate them fall short. Errors elude even The New Yorker‘s vaunted fact-checking operation. Translators of McPhee’s article about the Swiss army identified 140 new errors. Error-busting, then, is a Sisyphean task. Even when you fail, trying is imperative.![]()

8. Finding Voice

Everyone wants to stand out, to develop a “voice”–a distinct way of phrasing, scene-setting, describing, explaining–that sets him apart from other writers.

How do you do it?

To start, ironically, you imitate others. You find writers whose work you admire, and you study the structure and pacing of their work. You notice the way they introduce a topic, build sentences and paragraphs, describe a face or a moment, deploy quotations or metaphors, break down a complex idea into pieces, or transition from one idea to another. You isolate one of those tricks and you imitate it. Then you do it again and again.

Then the magic happens. “Rapidly, the components of imitation fade,” McPhee writes. “What remains is a new element in your own voice, which is not in any way an imitation. Your manner as a writer takes form in this way, a fragment at a time.”

Which is like life, more broadly experienced. We find something to admire and align ourselves with it. We practice, practice, practice until it’s fresh and belongs, wholly, to us. In this way connection with others allows us to become who we are.

9. Finishing Touches

Here’s where the writer’s fun begins. After a lot of grinding–hard labor to gather the pieces and figure out how they might relate to each other–you can develop the ideas and characters and scenes with some depth and care. You can find the details that express “the people and the places and how the weather was,” to quote Hemingway. You can find the words that express the ideas just right–les mots juste.

As it happens, McPhee’s daughters have followed in his footsteps as creatives. Two are novelists, one is an art historian, and another is a photographer. When they get stuck, they sometimes seek advice from each other and their father. McPhee shares this piece of advice he once offered his daughter Jenny:

The way to do a piece of writing is three or four times over, never once. For me, the hardest part comes first, getting something—anything—out in front of me. Sometimes in a nervous frenzy, I just fling words as if they were I were flinging mud on the wall. Blurt out, heave out, babble out something—anything—as a first draft. With that, you’ve achieved a sort of nucleus. Then, as you work it over and alter it, you begin to shape sentences that score higher with the eye and ear. Edit it again—top to bottom. The chances are that about now you’ll be seeing something that you are sort of eager for others to see. And all that takes time.

And when do you know you’re done? You just know. You run out of questions to ask. When you ask questions, you know the answer before your interviewee can respond. The scenes play vividly in your mind, in the right sequence, almost like a movie.

Nothing is random anymore.

At that point, you’re probably already thinking about the next story.

Postscript: A Personal Note

Many years ago, I got the time wrong for a meeting at Boston University. To pass time, I wandered over to the campus bookstore and found Levels of the Game. In describing a U.S. Open semifinal match, McPhee offers a glimpse not just of tennis and sports and strategy, but of the two Americas. Arthur Ashe was a black who grew up in segregated Richmond; Clark Graebner was a privileged country club kid from suburban Milwaukee. Subtly, McPhee reveals some of the underlying truths of race and class that don’t fit the usual ideological and partisan debates.

I sat on the floor and read until, in a jolt, I realized I had to hustle to my meeting. As I lifted myself off the floor, I knew what I wanted to do for my next project. With just a moment of thought, I decided to give the McPhee treatment to Game 7 of the 2001 World Series, when the Arizona Diamondbacks rallied in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game 7 to beat the three-time defending champion New York Yankees. The game had everything—the sport’s best players and personalities, the convergence of trends that were changing the game, and an emotional undercurrent owing to the 9/11 attacks that happened six weeks before.

While writing that book, The Last Nine Innings, I occasionally returned to McPhee’s work. I read his book on Bill Bradley and long New Yorker pieces on nuclear proliferation, oranges, and geology. I picked apart his work, looking for tricks of the trade that I could use myself. I did not want to be McPhee; only one person can do that. But he is a master of longform narrative, worthy of study and emulation. He is, I suspect, as immersed in both the substance and form of storytelling as anyone alive. I have long envied the hundreds of students who have learned his approach in his creative nonfiction classes at Princeton.

Now, with Draft No. 4, he has invited writers everywhere into his seminar room.