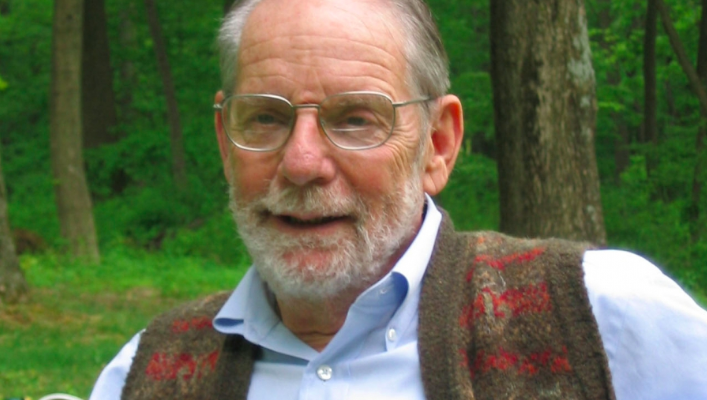

This is the first part of a two-part interview with Howard Bryant, the journalist and author of books about racism and the Boston Red Sox, the steroids crisis, and activism in sports and biographies of Henry Aaron and Rickey Henderson. You can read the second part here.

Howard Bryant is a writer’s writer. Passionate about his subjects and the craft, he has used the platform of sports to explore a wide range of issues–race, cheating, political activism, and heroism in an age of cynicism. His forthcoming book, The Heritage, addresses the rise of activism among athletes in the wake of police brutality and the Trump election.

A native of Boston and a graduate of San Francisco State University, Bryant has written for the Bergen County Record, Oakland Tribune, San Jose Mercury News, Boston Herald, and Washington Post. He is now a senior writer for ESPN the Magazine and a regular contributor on ESPN.

A native of Boston and a graduate of San Francisco State University, Bryant has written for the Bergen County Record, Oakland Tribune, San Jose Mercury News, Boston Herald, and Washington Post. He is now a senior writer for ESPN the Magazine and a regular contributor on ESPN.

Bryant has written four acclaimed books on sports and society. Bryant’s first book, Shut Out, explores Boston’s long history of racism in sports. Juicing the Game provides a riveting narrative of the steroids crisis in baseball. The Last Hero explores the life and legacy of Henry Aaron. The Heritage, which will be published on May 8, 2018, explores the arc of activism from Paul Robeson and Jackie Robinson and Muhammad Ali to the post-Ferguson wave.

To learn more about Bryant’s work, visit his website, howardbryant.net.

Charles Euchner: Can you describe some of your influences as a writer, when you were growing up?

Howard Bryant: Recognize that you can do this comes from reading people you admire and who are saying something to you; they’re saying something to everybody, but it feels like they’re speaking to you directly.

Growing up in Boston, I devoured the Boston Globe. I remember Derrick Jackson, Ellen Goodman, Bella English, Mike Barnicle. Then obviously, in sports, Peter Gammons, Dan Shaughnessy, Ian Thompson, Steve Fainaru …

The book that changed my life was J. Anthony Lukas’s Common Ground. That was the type of book where you’re reading about you. I grew up with the busing crisis in Boston. That book told you that there were stories that had national reach that were about you–that your experience had value. So would you rather see someone else writing about your community or do you have a responsibility to do it yourself? That’s what Common Ground gave me.

In the summer of 1989, James Baldwin got inside my head and he has never left. It wasn’t The Fire Next Time or No Name in the Street, it was actually Tell Me How Long the Train’s Been Gone, it was his fiction that hit me first. I had a friend at Temple who was reading Sonny’s Blues. A few months later I was in The Brattle and I bought a paperback and took my lunch and I sat outside and I read almost half of it sitting there. Then I moved to Just About My Head and Another Country … then The Fire Next Time and No Name in the Street and Nobody Knows My Name and that was it. That was as romantic a relationship you can have with a writer: He’s talking to me! There hasn’t been another writer where I thought what they were saying was tailor-made for where my brain was. That connection was so powerful.

CE: The great thing about Baldwin, to me, is the combination of simplicity plus passion. The simplicity allowed the passion to come out, because what he trying to do is be direct about a topic that nobody wants to be direct about.

HB: This was not theory for him. Baldwin was in the middle of it. He wasn’t a dispassionate reporter; he was in the movement, meeting with all these figures. But not only that. I watched [the documentary] I Am Not Your Negro and you see in those interviews that Baldwin was one of those guys who in basketball they would call a triple threat. Very few writers–Hemingway, Joyce Carol Oates, Toni Morrison–are equally adept at fiction and nonfiction. Baldwin had the third part of it too. He was a great speaker. Those interviews are just as powerful as what he puts on the page. And that’s the passion you’re talking about.

He’s our godfather, if you’re a black writer today. He said everything that spoke to us. You look at the influence he had on Ta-Nehisi Coates. Look at what Toni Morrison said about him. He was able to speak for you in that fearless way. You talked about being direct on a subject that others were indirect about. He and Malcolm X were able to speak about your experience, without asking permission and without asking for your acceptance. Baldwin wanted love, probably more than most writers. He was pleading as a writer, but he was unflinching. You don’t believe how many conflicts he has in the work, in the characters, whether it was gay, straight, white black, all of it. He was searching for that level of humanity. At the same time, he was able to say, “You, white America, I’m putting you on trial and I’m not asking forgiveness.” He was saying, “This is who you are and don’t ask me to make excuses for you.” That’s an incredible balancing act.

CE: And David Halberstam?

HB: From 1987 to early 1990s, there was the huge baseball craze in publishing: Roger Angell, The Brothers K [by David James Duncan], and Halberstam’s Summer of ’49. I devoured them. I remember reading these cruel reviews about Halberstam and one of the themes was that he couldn’t write. David Halberstam couldn’t write! I guess the point is that he wasn’t a prose stylist, he was not the guy who was going to turn a phrase the way Toni Morrison could or the way Tom Wolfe and Truman Capote could.

But Halberstam could explain to you a moment in time and why it was important, and say, “Here’s why this moment changed history.” When I was working on Juicing the Game, I asked him: “I have this idea but I don’t know how to get it,” and he told me about his concept of intersection. You pick a moment–you can’t pick too many, because then none of them matter–but you pick one or two or three moments where history could have gone this way but it went that way, and you report the hell out of those moments.

CE: I get that point about style. But my favorite Halberstam book is The Breaks of the Game. The style in that book is exhilarating. It was the same level of excitement–like jumping out of your chair–as the John McPhee book on Bill Bradley, A Sense of Where You Are.

HB: The two Halberstam books that really took off for me–one was October ’64, the book on the Yankees and the Cardinals, the other was The Fifties. That book is so dog-eared right now. He signed it. I try not to keep reading it because it’s signed and I don’t want to ruin it, but I do because, again, he was able to take these moments of this decade and explain why this decade was so significant. I also love The Children, about the civil rights movement.

Those three–Lukas, Baldwin, and Halberstam–taught me that there’s more than one way to write well. You can write well by being explanatory, by turning phrases, and by having amazing depth of information. Baldwin taught me to have your style, to say it the way you want to say it, and be fearless about it.

CE: What other writers have influenced your style … especially when you’re writing?

HB: When I’m on a book project, I never read nonfiction, and I certainly never read anything similar to the subject that I’m working on. I always read the most fiction when I’m writing a book. Very rarely do I read fiction when I’m not writing a book. This reason is, so I don’t, through osmosis, duplicate anybody. You want to sound like yourself.

I am a gigantic Larry McMurtry fan. I love westerns. Cormac McCarthy, although he’s a violent man, you want to talk about a stylist! If you read No Country or the trilogy with All the Pretty Horses, he has this style that is incredible in terms of his ability put you in a situation that is completely his–it’s his universe. I really love that. Talk about turning phrases. At the [killing] scene at the end he says, “Call it heads or tails.” You can write this long, flowery, heartbreaking death scene or you can do what Cormac McCarthy did, was was like: He called heads. It was tails, and he shot her. Could you write a more descriptive paragraph in two sentences?

CE: That’s Hemingway’s iceberg theory–keep most of the stuff unstated, below the surface. Once you’ve said enough, the reader can fill in the rest.

HB: That’s right. I repeat that sentence so often because people think that there’s one way to write and there’s really not. Sometimes the best way to say it is to say it. Find your way to get there and then don’t get in the way of yourself.

CE: When I first started reading Juicing the Game, was was struck by the great leap forward you achieved as a writer. You took your game to a completely different level. Am I right?

HB: One of the things about Shut Out is I love that book. It started my career as an author. But I wish it had been a second or third book because I didn’t have the feel–that’s what we talk about, finding your voice, finding out how you want to sound. I would love to do that book all over in so many ways. It was my first longform attempt. I was a newspaper guy so I was writing 800 words. Usually when you’re going to take on books, you go newspaper, 800 words; longform, 2,000 to 3,000 words; magazine articles, 4,500 to 6,000 words; and then books, 80,000 words. I went from 800-word newspaper articles to a 116,000-word book. There were times, writing Shut Out, where I was like, “Am I drowning here? Can I swim?”

Then when I got to do Juicing the Game, I got to talk with David Halberstam. He was incredibly gracious with his time and with his teaching.

Ideas don’t make books, characters make books. If you want to write a really good book, you’ve got to find someone to carry that idea through. Every story, you have to ask: Who embodies this idea? Then you have to make these people real. It will come off bland and disjointed if you don’t have a vehicle. You’ve got to find the people who exemplify the ideas. So people become metaphors. In Juicing, that was the first time I recognized that was essential. In Shut Out, I said, “OK, this happened, this happened, this happened.” It was all very informational. By the time I got to Juicing and The Last Hero, it was: idea/anecdote, idea/anecdote. It was: Who’s the person you can run this idea through? Tell me a story.

The universes I live in is so colorful. Baseball is hilarious. Your challenge is not to have information, but to present it in a way readers can learn about the world and also learn about things they didn’t know they were going to learn about. Like in October ’64, Halberstam talks about when Bob Gibson had a sore shoulder, he rehabbed it by washing his car. These are great details that you have to find to make it come alive.

CE: When you write about sports, you write about social issues–race, class, sexism, homophobism, labor, media, celebrity. Sports gives you a great platform to talk about all these things. But at the same time, you can’t get on a soapbox or too too far away the games. How do you do that balancing act, between sports a a game and sports as a place to explore all kinds of social issues?

HB: I never got into this because I was a sports fan. I got into this because I wanted to write Shut Out and that was going to be a serious book. The reason why i love sports. I’ve never met anybody in my life who loves sports more than Bob Ryan [of The Boston Globe]. He loves the games. He’s been doing this since before I was born and he still loves the games. You could call Bob Ryan right now and he’ll tell you about Reggie Cleveland’s 18-hit complete game. He still has the box score. He’s that guy. I got into this because I am an owner-versus-players labor guy. I love that sports is one of the few industries where the worker has leverage because of their talent. There’s only one LeBron James, there’s only one Kobe Bryant, there’s only one Tom Brady, and their talent creates a business model unlike anything other than entertainment. Their talent changes the business model. Thats what’s always made sports interesting to me.

It is a balance because the fan is not into it for that. The fan is not looking at a baseball game for the labor implications. This is their fun and games. If you want someone to talk about the wonders of Game 5 of the World Series, you should probably read Jayson Stark or someone else, not me. But if you want to talk other issues–like now, if you’re a manager, your job security has taken a major hit if you don’t win it all–that’s what I do.

It’s all about knowing yourself, knowing what your strengths are. Don’t be afraid to bring what you bring to the table. I’m not Bob Ryan. It’s not going to do me any good to write like Bob Ryan. It’s going to do a lot of good to write like me. If you want the inside stuff on the game, feel free to read someone else.

To get this right, adapt Mark Twain’s dictum–“When you catch an adjective, kill it”–to your comparisons. When you catch a fleeting pop-cult reference, kill it.

To get this right, adapt Mark Twain’s dictum–“When you catch an adjective, kill it”–to your comparisons. When you catch a fleeting pop-cult reference, kill it.

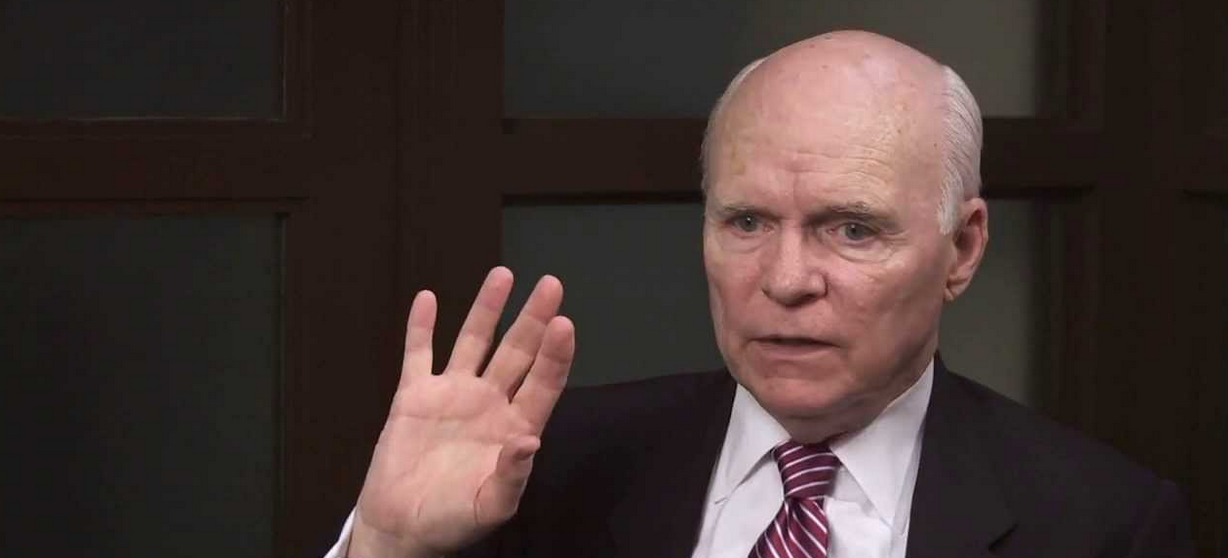

One interviewer who has never put himself above his subjects is Brian Lamb, the founder of C-SPAN and the host of Book Notes.

One interviewer who has never put himself above his subjects is Brian Lamb, the founder of C-SPAN and the host of Book Notes.