To write, you must first generate ideas. You can’t sit down at a laptop and just start spilling out coherent prose. Just as a builder needs construction materials, a writer needs ideas. And you need to figure out how to organize ideas–what’s most important and what’s less important, how to cluster the ideas, and how to identify the ideas that will arouse the reader.

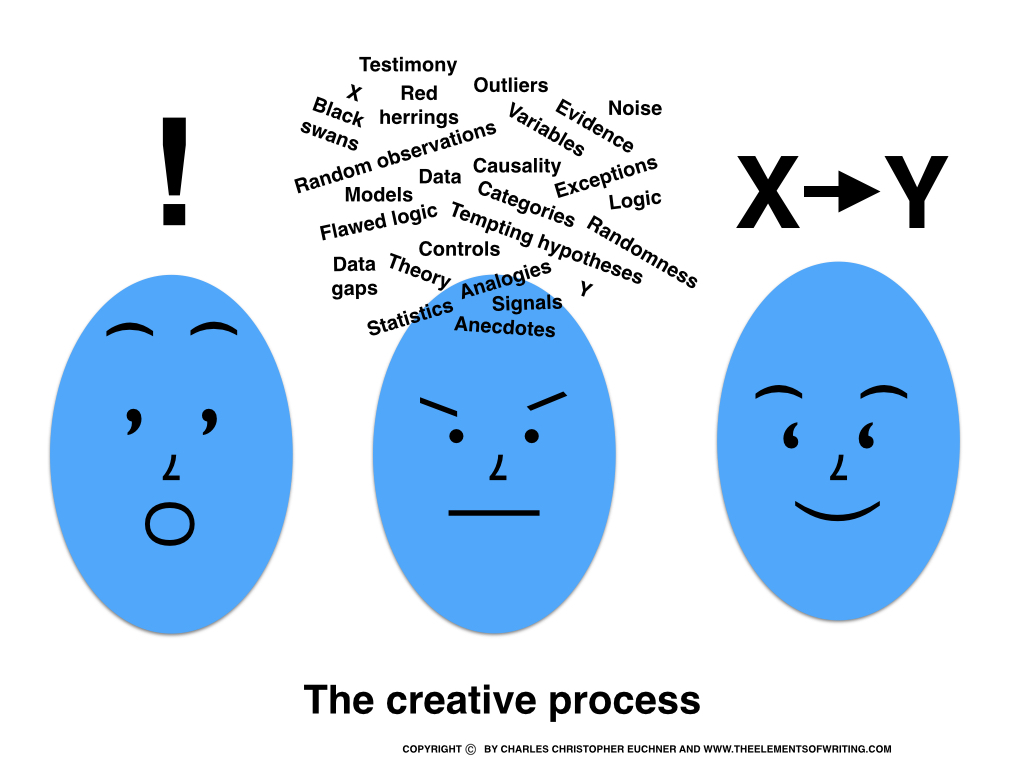

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.

So how does brainstorming work? Actually, brainstorming takes a number of forms. It doesn’t begin when you’re ready to write. It takes place when you’re sleeping and when you’re daydreaming.

So let’s look at the major dimensions of brainstorming.

Why Brainstorming?

To explore any topic, you must start with lots of research. But also get your subconscious involved. Allow your lifetime of knowledge and insight to contribute to your analysis.

When you tell yourself to do something, the brain rebels. Think of our failed New Year’s resolutions. We vow to stay on a diet, exercise regularly, pay bills on time, or control our temper. Despite our sincere efforts to make change, we fail.

The problem is twofold—narrow minds and resistance.

Making resolutions narrows the mind. Rather taking in the full range of possibilities, the mind focuses on the command’s subject. If I tell you not to eat ice cream, what are you going to think about? Ice cream.

Whatever you decide to do, your subconscious mind resists change. Our subconscious is a complex web of memories, associations, fears, and desires. Many of these thoughts we repress, so they feel illicit. But they remain, under the surface. And when they are challenged, they assert themselves.

Start With Research

Before brainstorming, do as much research as possible. When you read a book or article, write down a label for each idea in the margins. That way, when you go back to brainstorm, you can review all the key concepts in a few minutes.

Now, how do you arrange these ideas? Some writers cluster similar ideas together; others show connections between opposites. Some writers list data in one part of the sheet and general ideas or principles in another. Others cluster major concepts with specific data. One thing you must always do: draw diagrams and lines making connections among the ideas and data.

Whenever possible, draw charts and pictures. Show how ideas relate to each other. When you scribble, you excite your mind. You move away from linear thinking—first one thing, then another, then another … —when you draw pictures. You can see a whole bunch of ideas, and how they relate to each other, at a glance.

Simple stick figures work fine. Use them to illustrate the relations among characters (who), their passions and activities (what), the timing of actions (when), the location of activities (where), the reasoning behind activities (why), and their methods (how).

When you write, you need to arrange your ideas logically. But don’t rush this process. To brainstorm well, you need to create a free flow of ideas, without too much order.

Dreaming

A study at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, reported in the journal Current Biology, reminds me of my early days as a college teacher.

Back in 1988 and 1989, I was teaching fulltime at St. Mary’s College of Maryland while completing work on my dissertation. I taught three classes every week. Every lecture was brand new. I knew a lot about these classes but also had to learn as I went.

Every night, I was able to do all the prep work for two of the three classes. But I was too exhausted to prep for the third class. So, before turning in, I quickly reviewed materials for the third class. I made no effort to write a lecture.

When I woke up the next morning, I knew exactly what to do with the third lecture. I turned on my computer and completed the lecture in short order. That third lecture, as it turned out, was usually better than the other two.

The reason is simple. I primed my mind to do all the hard work while I was sleeping. My dreams took the raw materials — the review of class notes — and organized the material for me.

Ever since then, I have tried to go to bed with an agenda. Whatever problem was vexing me — as a writer, teacher, friend, family member — I try to figure out while sleeping. And it usually works.

I am fond of saying that writing is, more than anything else, a series of problems that need solutions. How am I going to organize this book? How am I going to open this chapter? What evidence do I need for this argument? What’s the best way to introduce a character?

Of course, you cannot solve problems without useful information. So you need to gather and consider as much information as possible before hitting the pillow.

The key to getting the brain to work while dreaming, I have found, is letting go. When I push too hard to solve a problem, I tend to freeze my brain. Not only that, but it’s also harder to fall asleep. You can’t dream if you don’t sleep.

So here’s the formula for solving writing problems:

1. Review all the information and the possible solutions.

2. Get away from the issue by getting ready for bed — brushing teeth, having a glass of water, and so on. Don’t eat or drink alcohol before going to bed. If I have even a glass of wine after 7 or 8, I have a hard time sleeping through the night.

3. If your mind is too active, take a melatonin pill so you can settle down and sleep.

4. Dream away.

5. When you get up, take up the problem you were trying to solve. Chances are, if you had enough information before sleeping, you will come up with at least one or two possible solutions.

Daydreaming and Doodling

When his friends and associates thought about Bayard Rustin, they pictured a restless man, moving kinetically at rallies and demonstrations, exhorting and advising Martin Luther King, speaking in his high-pitched faux British accent, and exposing himself to the worst kind of abuse because of his commitment of nonviolent action.

I had the pleasure of exploring Rustin’s life while researching Nobody Turn Me Around, my account of the 1963 March on Washington. And what a life it was. Rustin was probably the greatest polymath of the civil rights movement. He was a great speaker, strategist, theorist, writer, and organizer. He did more than anyone else to etch nonviolence into the movement’s DNA. And, for extra measure, he was a first-rate singer, a lover of art, and an inspiration to generations of activists in the labor, antiwar, civil rights, and gay rights movements.

Even though I can picture him speaking and singing and leading marches, my indelible image is of Rustin doodling.

When I worked my way through the archives of Rustin and the March on Washington, I found a number of his doodles. They were usually Escher-like images, with layers of squares that curved toward some destination. When I saw the doodles, I guessed that they helped him visualize the complexities of the movement in the tumultuous summer of 1963.

Then I found one of the interns at the March on Washington headquarters. Peter Orris was then a high school student in New York; in the intervening years he has become a doctor but remained active in social causes. He’s a smart and decent man. Did he remember Rustin’s doodles? Yes, he said. He was so impressed that he asked Rustin to autograph one of the doodles.

All this came to mind when I discovered a recent TED talk by Sunni Brown about the power of doodling. Contrary to doodling’s reputation — at best, it’s considered a lazy diversion; at worst, it’s considered a sign of moral laziness and inattention — Brown sees doodling as an essential part of learning and creativity.

She points out that doodlers remember 29 percent more of verbal content than non-doodlers. Even more impressive, doodling excites the senses. We perceive the world through four “modalities” — verbal, auditory, kinesthetic, and symbolic. If you can engage two of those modalities, you will work more efficiently and creatively. Doodling engages all four!

And so her proposed definition of doodling: “to make spontaneous marks to help yourself think.”

So, writers of the world: Doodle! Don’t press yourself when blocked. Don’t just make lists (so linear). Don’t refine definitions. Don’t just read more or interview more. Doodle! Awaken the doodler within!

Brainstorming: From Wildness to Order

When we ask ourselves questions, the brain responds positively. The brain loves scavenger hunts. When you state a goal in the form of a question—like “How can I avoid having a high-calorie lunch today?”—the brain shifts into search mode. It comes up with all kinds of possibilities, rather than resistance.

That’s why brainstorming is so powerful. It sends our brains into search mode. And when it searches, it opens up your whole mind—even ideas that have been buried for years.

So what’s the best approach to brainstorming? Start by writing down everything you know about your topic—on a single piece of paper. Look at all your ideas, all at once. Grab a big sheet of paper—you can buy an 11-by-17 sheet at a copy center—to hold all your ideas.

Get wild. Let your thoughts run free. Use the “divergence” strategy to generate as many creative ideas as possible.

What’s the divergence strategy? Businesses use “divergence tests” in hiring to find the most creative candidates. Here’s how these tests work. Interviewers ask job candidates to list all the ways to understand a word or phrase. Narrow, literal-minded candidates list only obvious ideas; creative candidates list a number of surprising ideas.

Here’s an example: Name all the possible uses of a book. You could say books offer reading materials, cutouts for posters, doorstops, and goods to barter and sell. You might use a book as kindling, weapons, writing surfaces, cutting boards, straight edges, fans, noisemakers, blotters, coasters, Rorschach tests, and symbols. How many more uses could you find for a book?

Divergence tests offer a good way to approach brainstorming too. The more ideas you scribble on your page, the more creatively you can explore a topic.