Years ago, I went to paradise in search of the secret of youth sports champions.

A team of work-class families from an old Hawaii plantation town of Ewa Beach won the Little League World Series in 2005. They beat the top-seeded American team, an affluent band of year-round players from suburban San Diego, and then they beat the defending champions from Curacao.

And they did it without breaking a sweat. As other teams collapsed physically and emotionally, the bunch from Hawaii won easily. Even when they were losing in the final game, they were loose.

And they did it without breaking a sweat. As other teams collapsed physically and emotionally, the bunch from Hawaii won easily. Even when they were losing in the final game, they were loose.

So what was the secret to their success?

The coach of the team was an ink-haired forty-something grandfather named Layton Aliviado. We met in the living room of Layton’s house in a development of Ewa Beach, a booming section of Oahu. Like other fathers on the team, Layton drove a truck for a living. Like the other parents, he was devoted to helping his kids go places he could never go—starting with private school and college. In his living room, he sat amidst baseball and football gear, trophies and balls, boxes of commemorative tee shirts, and pictures of his kids.

Layton described the team’s drills for hitting, running, and fielding. In all the baseball drills, Layton taught his young athletes to generate power from the lower parts of the body (the legs and butt), transfer that power with the core (the abdomen), and then to perform specific actions, like throwing and hitting, with the upper body (arms, shoulders, wrists).

Aliviado grabbed a bat to demonstrate how he taught hitting.

“One: stride forward.

“Two: get the hips going, get the hands going.

“Three: bring the hands around into the zone, snap everything forward.”

The key, he said, was to put everything in threes.

“In the beginning of the season, I do 1-2-3 drills,” he said. “I keep it simple for the kids. Everyone can count. Just count out what to do and explain by showing. Then they have it stuck in their heads: 1-2-3. I do the same thing with throwing and pitching. Every kid can count, right?”

That’s exactly what we need to do to master writing. Too often, teachers and editors fail to explain how to do what they demand . They say: “Keep it simple!” And: “Cut Clutter!” And: “Use details!” And: “Show, don’t tell!” And: “Tell a story!” But they don’t say how.

But the key is to break everything down into three parts.

The Power of Three

Groups of three work because they make sense of the world. We think in threes for logic (syllogisms), religion (father, son, holy ghost), dynamic relationships (two people and a disruptive third), architecture (foundation, walls, roof), politics (executive, legislative, judicial), economics (producers, products, markets), the learning process (demonstration, trial, correction), the psyche (id, ego, superego), and families (mother, father, children). Threes give us simple but dynamic models for understanding the world.

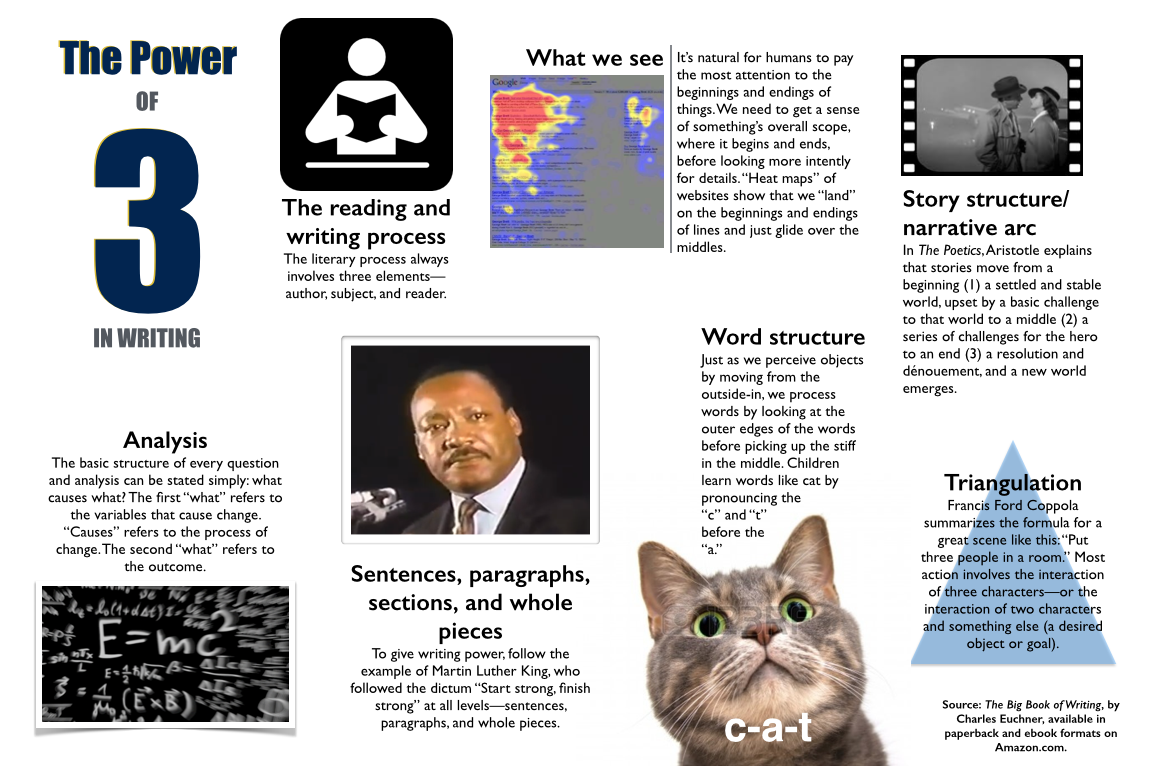

The core skills of writing—storytelling, construction, and analysis—begin with that one-two-three structure. Linguists have found, in fact, that children learn words and language in three parts. To understand a simple word like cat, for example, a child first learns the beginning (the letter “c”), then the ending (the letter “t”), and finally the middle (the letter “a”). One, two, three.

The one-two-three code overlaps for all three writing skills. When you learn the 1-2-3 Code, you learn all you need to know about writing.

The reading and writing process: The literary process always involves three elements—author, subject, and reader.

Story structure/narrative arc: In The Poetics, Aristotle explains that stories move from a beginning (1) a settled and stable world, upset by a basic challenge to that world to a middle (2) a series of challenges for the hero to an end (3) a resolution and dénouement, and a new world emerges.

Triangulation: Francis Ford Coppola summarizes the formula for a great scene like this: “Put three people in a room.” Most action involves the interaction of three characters—or the interaction of two characters and something else (a desired object or goal).

The content of stories: Most stories concern the gossipy question, “Who’s doing whom?” Readers want to know about relationships. Relationships reveal all in stories. Word structure: Readers first process the beginning, then the end, and finally the middle.

Sentence structure: Most good sentences begin with a core of subject, verb, and object/predicate. If you build that three-part core into every sentence, the reader will always follow what you say.

Sentences, paragraphs, sections, and whole pieces: The 2-3-1 principle—put the second most important idea first, put the least important information second, and put the most important stuff last. I also call this “start strong, finish strong.”

Analysis: The basic structure of every question and analysis can be stated simply: what causes what? The first “what” refers to the variables that cause change. “Causes” refers to the process of change. The second “what” refers to the outcome.

Why Threes Are Powerful

Threes are powerful for three reasons.

Pattern recognition: The human brain is a pattern-recignition machine. To gain control over our lives–to understand what’s happening and what might be about to happen–we see the world as a three-step process.

Suppose I tell you a number—2, for example. Do you see a pattern yet? No, of course not. Suppose I give you two numbers: 2 and 4. Do you see a pattern? You bet. There are two obvious possibilities. I might be doubling the numbers … or I might be counting by twos.

When will we really know the pattern for sure? With the third term. If the pattern is to increase the numbers by two, then the pattern will be 2, 4, 6. If the pattern is to double the numbers, the pattern will be 2, 4, 8.

Prompt-process-resolution: Every day, researchers tell us, we experience 50,000 to 70,000 thoughts. From the time we awaken to the time we fall asleep, a long train of troughts enter our minds, unbidden.

Those thoughts have a 1-2-3 structure. First we get some kind of prompt. Something happens to draw our attention. The alarm goes off, a driver honks, an aroma wafts across the restaurant, a group of people burst into a house.

When we get that prompt, we process it. We try to make sense of it. When the alarm sounds, we get pulled out of our dream state and into the real world. When someone honks a car, we are startled and pay attention to the traffic and possible pronlems on the road. When the aroma wafts across the restaurant, we wonder it it’s our order or someone elses and also wonder what it is. When people burst into a house, we look up from our book or laundry (or whatever we’re doing) to see who has arrived.

When we process information, we have an internal dialogue that can be short or go on for a while. Once we have processed the information, we resolve the issue.

Dynamism and sturdiness: Mathematicians say that a triangle is at once the sturdiest and most dynamic of all shapes. Moving one corner alters the other two, but does not necessarily upset everything. Triangles create a process of constant adjustment. No wonder, then, that we see triangles in all structures—of art, literature, scientific inquiry, you name it.

Why do so many systems and structures work so well in threes? I’m not sure, but the dynamic relations of a lover’s triangle offers some hints.

Think of Oedipus, Laius, and Jacosta (Oedipus Rex)…Catherine, Heathcliff, and Edgar (Wuthering Heights)…or even Carrie, Big, and Aiden (TV’s “Sex and the City”). A couple can achieve some stability, apart from the world. But when you introduce some outside force—say, a former lover of one of the partners—that stability totters.

How does the arrival of the third party affect the couple? Does it bring them closer together? Create temptation? Jealousy? Anger? Fear? Whatever the case, the couple is challenged—singly and together—when they have to deal with outside forces. The third element, then, reveals all.

Threes in Stories

The greatest single work on storytelling, Aristotle’s The Poetics, describes three parts to all stories.

Part 1: The World of the Story. In the beginning, we meet the story’s hero and learn about his or her home, values, desires, and challenges. We see what’s “normal,” what kind of “comfort zone” the characters inhabit. We also see hints of characters’ limitations.At the end of the first part, the hero must face some crisis or answer a “call to action.” Most people are reluctant to answer the call. They have established a life already and don’t want to do the work — or acknowledge their own psychological or moral limitations — and so they try to avoid doing things differently.

But before long, the hero realizes that he has to do something to respond to the challenge. Typically, he addresses a small aspect of the challenge with the hope that the larger crisis will go away. But it doesn’t.

Part 2: Rising action. The second part of the story focuses on a series of crises. The hero tries, again and again, to avoid the crisis. But to fend it off, he has to confront a piece of it. Each time he confronts a piece of it, he hopes the problem goes away. But it doesn’t. So he takes on a bigger piece of the problem … and then a bigger piece … and then a bigger piece. Finally, over time, the hero learns the enormity of the crisis. He also begins to understand that he cannot remain in denial.

Part 3: Resolution. And as he deals with these pieces, he comes to a new understanding of himself and his situation. And so the story reaches a climax. The hero has to take on the crisis in its entirety.

By the time of the climax, the hero opens his mind and expands his skills.

And so, in the final part of the story, the hero reaches a new recognition of his situation. And he reverses his previous approach to the crisis and to his life. This is what Aristotle called the denouement, the winding down of the action. Now, the hero settles into his new life with a new understanding of his own character and the world.

Threes and the Inner Structure of Writing

The structure of a story offers that same three-part “template” for all other elements of writing. In fact, everything else is really just a particular kind of story. A sentence is a mini-story. A paragraph is a slightly larger drama. And so are sections and larger pieces of writing — even non-narrative pieces like emails, memos, reports, and analysis.

All of these elements of writing take that 1-2-3 format, from beginning (world of the story) to middle (rising action and conflict) to end (resolution and closure).

Once we master mechanics, we can move into the most abstract challenge of writing — analysis. Whether we’re analyzing problems of science, medicine, policy, business, psychology, or other topics, we are really telling a story. What makes analysis different is that the story concerns concepts and categories, rather than particular people,. places, actions, and outcomes.

Storytelling provides just the first building block of all writing skills. Once we master storytelling, we can easily develop skills in mechanics of writing — sentences and paragraphs, grammar and punctuation, editing and style.

We see the three-part code wherever we look, in storytelling and in the movement from storytelling to mechanics to analysis. Consider:

• The core of a sentence: Subject-verb-object

• The sentence and paragraph: Start strong, finish strong, with “bridge” material in the middle

• The elements of a great scene: Triangles

• The joke or scene: Background/setup, expectation, surprise

• Dialogue: Positive, negative, positive statements (or negative-positive-negative)

• Cliffhanger: Situation, response, unresolved conclusion (with lots of guessing)

• Sensory sensations: Visual, auditory, kinestheticDialectics: Thesis, antithesis, synthesis

• Analysis: Dependent and independent variables and result

Here’s something magical: If you can get in the habit of looking for threes in whatever you do — writing a sentence or paragraph, structuring a scene, debating an idea — you will not falter.

What Are the Threes in Your Work?

Threes in your life: Make a list of the threes in your life — relationships, ideas, conflicts, events. Identify how these three elements came together, what kind of conflict resulted, and how that conflict was resolved.

Your three-part story: Sketch out, as quickly as possible, the three-part structure of your NaNoWriMo novel. Follow Aristotle’s narrative arc, moving from the beginning (“world of the story”) to the middle (“rising action” of ever-more intense conflict), and end (recognition and reversal, setting into a new world of the story).

Scenes: Write three scenes, at least 700 words apiece. Use Aristotle’s arc for each scene. Open by showing the characters living in their normal, everyday world — only to confront something new, unexpected, and threatening. Show the characters deny and then, reluctantly, deal with the challenge. And end with the whole situation getting resolved, with the characters at least a little more aware, knowledgable, and capable.

(Click the poster to download.)