What if writing was the most natural skill that we possess? Would that change how we teach children to read and write … or develop as writers throughout their lives?

Researchers on evolutionary biology tell us that storytelling is the essence of the human experience. Other species eat, drink, play, sleep, and mate. Some species use language and tools. But as far as we know, humans are the only storytelling species.

Young children delight in hearing and telling stories. Given the chance, they will talk endlessly about their experiences, both real and make-believe. So what if we tapped that energy and that intellectual firepower? What if we taught kids how to put those stories down on paper, even before they learned how to read?

These are some of the issues I explored as a staff writer for Education Week. This piece comes from the December 22, 1982 issue.

By Charles Euchner

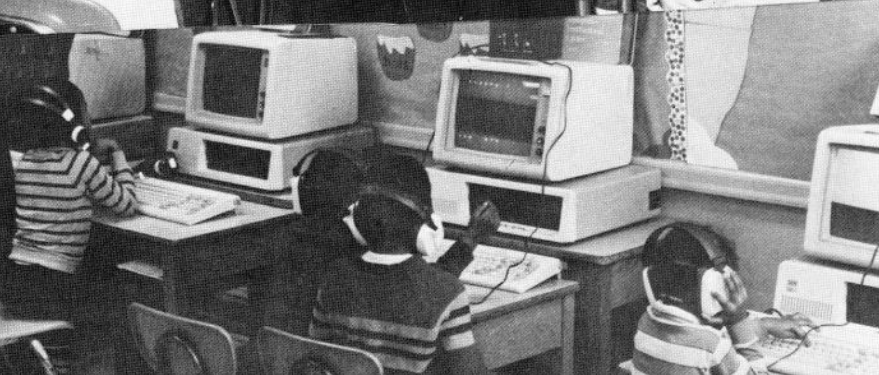

Once each hour at Congress Heights Elementary School in Washington, D.C., kindergartners and 1st graders gather and neatly put away their supplies in the “Writing to Read Center.” Without instructions, with few words among themselves, the students line up at the door to return to their regular classrooms.

They file out in two lines–one for boys, the other for girls–and soon the room is filled again with a new group of equally well-mannered students who go to their five workstations and get to work without any directions from the teacher or aides.

It is a scene that would not have surprised Frank N. Freeman or Benjamin DeKalbe Wood, who 50 years ago wrote the book that would inspire a retired teacher named John Henry Martin to start the writing experiment that involved these Washington public-school students.

Freeman and Wood, who studied the effects of typewriters on the classroom performance of about 15,000 elementary-school students from 1929 to 1931, found that the children were fascinated with the machines and had much better work habits when they used them.

The Depression-era researchers quoted a 1st-grade teacher: “I notice an awakening sense of responsibility; the children remember to put away typewriters and leave offices in order; they are pleasant and polite in choosing helpers …”

Not incidentally, the researchers also found improvements in academic performance. They were less certain of the typewriter’s value in lower grade levels, mostly because of the inadequate testing methods for younger students.

On a recent tour of schools experimenting with his “Writing to Read” program, John Henry Martin did not express any doubt that his contemporary version of the program works.

Tests have shown, he said, that a combination of computer, typewriter, workbooks, and pictures makes it possible for children to write almost as soon as they enter school.

“I proclaim it,” he told a group of Washington principals. “It works.”

The “it,” the Florida-based consultant says, is a classroom situation that combines “truly interactive” machines with a child’s natural desire to know and express himself in words. After seven years of developing and testing his idea, Martin concluded it worked because children of varying backgrounds scored well above national norms in reading and writing tests.

“It’s amazing,” Martin said, “that with the research of the last 50 years, and especially the last decade or so, we have failed to use the typewriter and other things … that are truly interactive.”

Martin’s project, financed by the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM), now involves 10,000 students from a variety of economic and educational backgrounds. Besides the 15 schools in Washington, the experiment includes districts in Florida, Minnesota, North Carolina, and Texas, and universities in California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

The Educational Testing Service (ETS) in Princeton, N.J., has contracted with IBM to evaluate the program.

The program is based on the premise that students already have many ideas to express by the time they enter school. A kindergartner has a working vocabulary of 4,000 to 5,000 words, said Martin, and just needs to engage more in “multi-sensory-receptive” activities to express ideas.

Children are wrongly taught to read before they learn to write, Martin says, but it has not always been that way. Prior to the early 20th century, students expressed their ideas in writing from “day one,” Martin said.

“In the past, children used a slate and chalk to, using the old expression, ‘make their letters,”‘ Martin said. “Sometime between 1910 and 1920, writing and reading were made into separate processes.”

‘Positive Reinforcement’

With the stress on reading before writing, Martin said, students do not receive the “positive reinforcement” that the behaviorist B.F. Skinner identified as an essential part of learning.

Children in the “writing to read” program work each day for one hour. They work with partners of their own choosing at workstations for computer work, typing, workbook exercises, creative writing, and listening to tape-recordings. They also work on miscellaneous projects, such as labeling and matching pictures with appropriate written material.

The students use all letters of the alphabet except Q and X, and a set of letter “blends” such as oi, ei, th, sh, sc, and gh.

Teachers and computer programs, which give and receive sound, teach the students how to pronounce the letters and blends and how to use them in words.

At the computer station, the student strikes the terminal’s keyboard when instructed by the program, then watches as the letters and blends fall into place to spell a word. At each step, the student hears then repeats the sound.

After completing 10 “cycles” of instruction, the student will have learned the 42 phonemes he needs to write about almost any subject. As soon as the student has mastered these basics, he can begin to write strings of related sentences and complete essays, paying attention to the grammar and spelling that before would only have hindered the writing flow.

The typing skills, which Martin said most students should be able to develop in the 1st or 2nd grade, will not only give the students a head start on working with computers but will also enable them to write much faster and more creatively throughout their lives, Martin said. Martin said his approach differs from the Depression-era experiment and from other current uses of computers in the classroom because his approach is “truly interactive.”

“The typewriter, by itself, is not interactive, and the cathode ray tube is not interactive,” he said. “What makes this interactive is that it gets students to make physical, bodily responses.”

Martin said that he adopted the program’s components only after eliciting such responses with a broad cross-section of students–from the gifted to the average to the slow learners, from those in small groups to those in large groups.

The approach to writing was tested for two years with a group of 60 students at the University School of Nova University in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. The striking results there, Martin said, convinced IBM officials that a test with a larger sample was needed.

Joseph Randazzo, the University School’s headmaster, said 1st graders who learned under Martin’s program scored 2.7 on a reading grade-equivalency test, while others scored 1.8. Half of the entire group scored in the 94th percentile nationally on the test, Randazzo said.

Career Start

Martin started his career 45 years ago in a one-room schoolhouse in Alabama. After serving with the Navy in Europe in World War II, he worked as a teacher, principal, curriculum consultant, and superintendent in seven districts on Long Island and in New Jersey.

On the side, he has done extensive consulting, serving on panels for two presidents.

Martin said he first became interested in the use of typewriters and other “multi-sensory” instruments when a friend recommended that he read the Freeman-Wood book, which carries the bulky title, An Experimental Study of the Educational Influences of the Typewriter in the Elementary School Classroom.

Martin has toyed with the idea for years since. Seven years ago–bored with a retirement forced on him by a heart attack–he decided to study it in a clinical setting. He took his proposals to Abraham S. Fischler, the president of Nova University, and soon started soliciting money for his work from the private sector.

The 1932 book, Martin says, now occupies the prized position on the coffee table in his Fort Myers, Fla., home.