Charles V. Bagli is the best investigative reporter on real estate in the American capital of real estate.

Reporting for The New York Times, Bagli tracks the big deals and the seismic shifts of the city’s development and land use—and the often-dirty politics of the industry.

Journalism was not on Bagli’s mind until his late 20s. He went to Boston University to become a filmmaker but the school of communications required students to wait until their junior year. By that time, he was involved in the antiwar movement and was working with the radical historian Howard Zinn. He worked as a labor organizer for six years. Then, as a husband and new father, he says, “I decided I had to grow up.” So he applied to be a plumber’s apprentice in Springfield, Massachusetts—and he applied to Columbia Journalism School. He got into Columbia and took his family to the big city.

Journalism was not on Bagli’s mind until his late 20s. He went to Boston University to become a filmmaker but the school of communications required students to wait until their junior year. By that time, he was involved in the antiwar movement and was working with the radical historian Howard Zinn. He worked as a labor organizer for six years. Then, as a husband and new father, he says, “I decided I had to grow up.” So he applied to be a plumber’s apprentice in Springfield, Massachusetts—and he applied to Columbia Journalism School. He got into Columbia and took his family to the big city.

Right away, he had doubts. A professor heavily critiqued his first submission. “The professor just rips it apart and I’m sitting with my head in my face and I’m thinking, ‘Oh my God, I’ve done the wrong thing,’” Bagli remembers. “Fortunately, I hung around and improved.”

In retrospect, Bagli had the right stuff all along. He loved telling stories, even if his writing was “just throwing words on paper and hoping people would wade through to understand it.” His proudest moment in high school was screening a short movie that ended with the hero “running across a field and there’s a pretty woman and the Dylan song comes up, ‘If dogs run free, why can’t we?’” The audience loved it. Heady stuff.

Bagli also liked spending time with people from diverse backgrounds. “I always get energized when I bump into people. As a journalist I am constantly meeting new and different people.”

Because of his organizing background, Bagli figured he would be a labor reporter—“not knowing there weren’t labor reporters anymore.” He wrote for the Brooklyn Phoenix, Tampa Tribune, Morristown Daily Record, and New York Observer before landing with The New York Times 20 years ago.

Charlie Bagli met with my class “Writing the City,” at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation, in October 2018. Here are some excerpts from our class conversation.

Bagli decided to embrace covering real estate, one of the orphans of journalism. Real estate is a difficult beat for two reasons. First, real estate coverage often involves fluffy PR pieces packaged with advertising, so reporters run into trouble with editors when they take a critical approach. Second, real estate is a complex topic that drives away reporters who want to rise quickly by covering sexier beats.

I wasn’t intimidated. I became self-taught. When I got a job at The Observer in 1987, I was covering the east side of Manhattan, from 14th Street to 96th Street, and there was a building boom going on. One by one, I met the developers and their lawyers and their PR people—and their opponents on projects too—and I made my own maps of who owned what. I set out to know the subject well so people couldn’t BS me. I wanted to become something of an expert.

The beat I have covered for 30 years is at the intersection of politics and real estate in New York. I thought real estate was one of the twin pillars of the economy [with finance]. You could not know New York without knowing real estate. In New York the mayor is a powerful figure and the city council not so much—except in one area, which is land use. Look at every politician, where they get political contributions, it comes from real estate. Real estate gives inordinately at both the city and the state level.

To make complicated topics understandable, a real estate reporter has to avoid insider lingo and find pithy ways to express complex, mind-numbing issues.

Because the subject is complicated, you have to constantly put yourself in the mind of the reader. What do they know? What can they get through? I can’t use jargon. Do you know the term ULERP? It means Uniform Land Use Review Procedure. I don’t use that term in a story. I’m always looking to break things down in a brief and useful way.

So you have little techniques. During a brief stint as a business reporter in New Jersey, I was doing a story about popcorn. I can’t remember if popcorn was going up or down. Anyway, I wanted to illustrate how much people ate popcorn, I calculated how much space in Giants Stadium would be filled with all the popcorn kernels people used in a year. It’s a lot of work for one sentence, but people know what you’re talking about.

In 2013, Bagli published Other People’s Money, the story behind the development and redevelopment of Stuyvesant Town in Lower Manhattan. The book grew out of his reporting for The Times on the redevelopment of the complex.

I got a tip in 2006 that Stuyvesant Town was going up for sale. I started looking into the whole history and writing it into my stories. The place was sold for a record-setting price. Anyone who knew about housing thought they paid too much—it was like a death march from the day they bought it in December 2006. They went out of business in January 2010. Meanwhile, over 10,000 apartments, 80 acres, were demolished.

Writing a book is always a journey into what you don’t know—after thinking you knew everything. Bagli was especially intrigued by the story behind the original decision to create the complex.

I thought I knew the whole story and I started digging in more. It ranged from meeting someone at a bar who said, “I know someone who lived in Stuy Town.” I met this succession of people, all with fascinating stories about Stuy Town and its culture. Like Playground 9, if you couldn’t play really good basketball you can’t get on the court. Catholic kids went to Catholic schools, Jewish kids went to public schools. It was a fascinating place.

In the 1940s—Manhattan was all working piers on East Side and the Jersey side, and near the piers were factories and warehouses, stonecutting operations and breweries. That started to fade from the scene and Mayor [Fiorello] LaGuardia was looking for new housing to deal with New York’s perpetual housing crisis. The insurance companies were some of the biggest in the world and they were huge employers—people filling out forms. Met Life was the biggest corporation in the U.S., with its headquarters on Madison Avenue and it was like a little city. They had a small hospital inside an a couple levels of cafeterias. LaGuardia and Moses bullied Met Life into thinking about it.

When Met Life said, ‘We’ll do this,’ they wanted to knock down 500 buildings. In Met Life’s library they had pictures of all the buildings. They didn’t want to replace any schools or churches. They wanted complete control over who entered this complex. This was possibly the first gated community. They didn’t allow black or Latin families to move in.

The chairman of Met Life was an interesting guy. He left school at 14 and saw people going into the Met Life building and got hired to work in the mailroom and he rose to become chairman. Part of his rise was based on taking over some buildings that Met Life had financed and went bankrupt and he made them profitable. New York was expecting a million GIs to come home. So they built Stuy Town. It had a legendary status, with a 10- to 15-year waiting list to get in. Lots of firefighters, teachers, cops. And the people who lived there stayed there. It was a haven for the middle class.

I felt like an archeologist. I discovered letters back and forth between LaGuardia and the chairman of Met Life. The first letter from LaGuardia was basically, “If a person is otherwise qualified, you can’t discriminate based on race.” Scrawled on top was written “not sent.” The response from chairman was “not sent.”

“Creative destruction” is a constant subject of Bagli’s work. In 1967, families in the Lower East Side were forced out of their homes to make way for an urban renewal project. After the buildings were demolished, real estate and political interested battled over the area. Finally, the Bloomberg Administration brokered a deal to build new housing and former residents were invited back. That’s when Bagli met David Santiago, who was planning to move one of the units.

“Creative destruction” is a constant subject of Bagli’s work. In 1967, families in the Lower East Side were forced out of their homes to make way for an urban renewal project. After the buildings were demolished, real estate and political interested battled over the area. Finally, the Bloomberg Administration brokered a deal to build new housing and former residents were invited back. That’s when Bagli met David Santiago, who was planning to move one of the units.

I always though the different neighborhoods were what made New York so interesting. I loved walking through garment district, that was one of the few places where you could see people actually working as opposed to disappearing into glass towers. There was the printing district, the flower district. These places are gone now.

In the 1960s they ousted all these Puerto Rican families and said they were going to build new housing and nothing was built for 50, 60 years—they were parking lots all that time. They never made good on the promises. Racial and ethnic politics was why nothing was built. There had been a series of coops in that neighborhood. Every time there was a plan to build housing, the coops fought it. They were able to defeat every attempt. They said we need jobs, not more housing—they didn’t say they didn’t want minorities.

They were opening the first building and a lot of people were returning to the neighborhood. I found David Santiago. He was a restaurant guy. Then a couple weeks after the building opened, I got a call from one of the activists and she said, “David died the day he was throwing this housewarming party.”

It was so interesting when he was alive to talk about the neighborhood. It was a poor polyglot neighborhood, with the Puerto Ricans and the Italians mixed in with the Chinese and a large Jewish community. David had these memories that were really interesting—and increasingly forgotten—as this tsunami of gentrification washed over Manhattan and Brooklyn.

His was a good story to tell because he reflected what happened in that neighborhood. His family was pushed out when he was seven. He had a wisdom about what the neighborhood was about. He had lied about his age and joined the Marines. Every experience was different but he reflected something about the whole neighborhood. He talked about the mobster in the social club that would give him a coke in green bottles.

His death gave me the room to talk about him. So I was sucking up all the details. A lot of stuff doesn’t get in, but of you don’t have it all, you don’t get that one telling detail that just makes the story.

The first job of a journalist is to get the story—the names and places, the events and consequences, all with good sourcing and evidence. The second job is to make it interesting. Sometimes you get something exciting but “bury the lead”—that is, put the best stuff where a reader might not find it.

I was working at the Tampa Tribune in Hernando County. It was like the old South there. I was the new guy so I was covering cops and courts. One day I heard over the police radio that something was happening at a nursing home. I went over and a guy went in with a gun and shot his wife and he turned it on himself.

My job was to talk to everyone about it. I went to their trailer and talked with his son. They owned a Honda touring bike and went everywhere together. The son ended by saying, “This was an act of love,” because his mother was wasting away and his father couldn’t bear to watch that. That’s a golden line—an act of love juxtaposed with the murder. I buried it in the fifth or sixth graf. Later I thought, “What were you thinking?”

A lot of people look for the first couple grafs and then they’re gone. When it says “Continued on page 7,” how many people take the jump?

With the rise of the Internet—and the shrinking “news hole” in print editions—newspaper reporters do not have as much space to explore their subjects.

The size of stories is smaller than it used to be. The editors use to say try to keep it under 2,000 words because otherwise it becomes a “special project” and then more editors get their hands on it and muck it up. Now it’s more like keep it to 800 to 900 words. So you have to condense.

You know you’re done, ready to go, when you’ve answered all the questions that your editor asked.

As an established investigative reporter for The Times, Bagli has freedom to roam around the city and explore all possibilities. That means spending time on the street and following up tips. Some tips lead nowhere. Others lead to scoops.

Sometimes you get a call out of the blue. You know Felix Sater, the Russian pal of Trump? I write about him in 2007. I got an anonymous call telling me about this guy Felix who changed one letter in his name so you couldn’t Google his past. One night he’s celebrating at a bar on Third Avenue and he gets in an argument and breaks a Margarita glass and stabs the guy in the face—he guy had 100 stitches—and he runs and the cops caught him. He was part of a mob scene of Wall Street, pump and dump. He was also working on Trump Soho, a condo/hotel. It was a financial disaster.

So this [tipster] is telling me these stories. I’m thinking, this is great if it’s true, but how much time am I going to have to figure out whether its true? You’re constantly doing triage and sometimes you’re right and sometimes not.

Turns out everything this guy said was true. I didn’t know his name but people call you all the time and sometimes they’re BS. I heard when he was indicted for the Wall Street scam and I got the police report when he stabbed that guy in the bar. I called American University, which had a center that tracked Russian mobsters and his father was in the mob. I figured out my source—he had been indicted with Felix for this scam on Wall Street and he was a straight guy and the worst day of his life was when he met Felix. So it was revenge, absolutely.

If you lie to me, I consider it a cardinal sin. If I fail to ask the right question, that’s only a venal sin. This is the Catholic in me. I want to put the fear in them, that if they ever lie to me I will kill them. It turned into a great story. I thought it would break up his relationship with Trump but it didn’t.

Like prosecutors—think Robert Mueller—investigative reporters work their way from the outside to the center of the story. So Bagli made sure he had all his facts about the Trump-Sater relationship before he called Trump, a longtime source for decades.

This is my interview with Trump.

This is my interview with Trump.

“Donald do you know this guy Felix Sater?”

“No, not really. I’ve met him and I know the chairman of the company, Bayrock.”

The chairman was a former Soviet official who became a billionaire, who’da thunk it?

“Oh, didn’t you go to Colorado with Felix?”

“Colorado? I don’t know if I’ve even been to Colorado.”

“No, Donald, you remember you gave one of your inspirational speeches there. Felix was there.”

“There were thousands of people there. How can I account for every one of them?”

“Yeah, but Donald, he got into the limousine with you when you left and then you then went down to Denver and talked to this developer…”

I like to have the answers to all my questions before I ask them. That way I know when somebody’s … fibbing. So I wrote the story [thinking it would create a split between Trump and Sater] but the relationship continued though 2016. And then he became part of history.

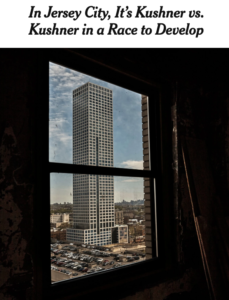

Sometimes the best stories are outside the center of the industry. Jersey City and other markets across the Hudson River have boomed as New York real estate prices have pushed people out of the city—and as developers have speculated wildly.

I did a story recently about Journal Square in Jersey City. I walked around and thought this is not a neighborhood. There are so many streets criss-crossing. Its hot because the waterfront is done, Grove Street is done. The next stop on the PATH train is Journal Square. So it’s going to happen.

You have the two Kushner brothers who hate each other and they want to build three towers each. It’s a recipe for disaster. You can’t put that many units in a neighborhood all at once. They compete with each other. Murray Kushner’s first tower is up. Charles had an empty lot and lost authority from the city. He thinks he’s persecuted because of his relationship with the Trump administration.

You have the two Kushner brothers who hate each other and they want to build three towers each. It’s a recipe for disaster. You can’t put that many units in a neighborhood all at once. They compete with each other. Murray Kushner’s first tower is up. Charles had an empty lot and lost authority from the city. He thinks he’s persecuted because of his relationship with the Trump administration.

I still wonder whether that neighborhood is going to turn. The next stop is Harrison, where they’re building like crazy near that soccer stadium. A lot of public money, idiotic money I thought. Ten to 15 years later, they’re not building. It’s a tiny community across the river from Newark.

There’s a lot of outflow from New York because New York is wildly unaffordable. If you’re on the outer rim with public transportation you’re in good shape. You can get from Newark to Penn Station in 15 to 20 minutes. Try to get from Times Square to Coney Island in less than 90 minutes.

Before going all-in on a story, Bagli likes to visit the neighborhood and see what it’s like.

I’m thinking about doing a story on the Museum of Natural History. They want to expand [by] 230,000 square feet. About 11,000 square feet, or a quarter acre, would encroach on Theodore Roosevelt Park. Some residents have sued to stop the expansion. I want to go and see how it’s used—how many are local people walking the dog or teaching a kid to ride a bike, and how may are tourists using the museum. You could say it’s only 100,000 square feet, but sitting in the park and getting seeing who does what the story.

There are real tradeoffs here. Is this a matter of “rules are rules,” so they shouldn’t get the park space? Or should other considerations come to play? You’ve got to be there and know the people in the area—who lives and who are the businesses.

Before deciding whether to write the story, Bagli decided to attend a court hearing on the activists’ challenge of the museum takeover as “arbitrary and capricious.” Even if a museum’s use of a quarter-acre of public space might be seem a minor issue in a city of 8 million souls, it illustrates the broader issue of the private use of public land.

This issue of parkland is a big thing in New York City. In Queens, at Flushing Corona Park they’ve already carved off for a big piece for tennis and then the Mets stadium and in the Bloomberg era they wanted to put a soccer stadium there. Why are they handing it over to a privately owned entity and shortchange the rest of the neighborhood?

In the park there’s also some crummy soccer fields and very active leagues. The owners of the leagues say we’ll renovate the fields and run clinics. So you had different views in the community. You had people who were doubled and tripled up in housing and others who lived in community and their kids played soccer and it seemed tantalizing. But it’s more space for private use instead of public use. That’s an issue.

Sometimes, news coverage moves beyond the public enthusiasm for certain development and exposes the secret deal-making of powerful elites.

The High Line is nice but I only hear foreign languages there—it’s a tourist trap—and you can’t stand still, you’ve always got to dodge people. It’s a very expensive bauble and it’s for the tourists.

There’s a dirty secret involving West Side zoning. In 2005, it was owned by CSX Railroad and the city was trying to get CSX to take it down. Over time, these guys came up with the idea of turning it into a park and raised public and private money. The landowners underneath wanted it down so they could do something with their property in the shadow of this structure.

Daniel Doctoroff [the top economic development official under Mayor Michael Bloomberg] wanted all this stuff to happen on the West Side. Doctoroff said, “I’m going to rezone your land. If it’s manufacturing, its worth so much, but if it’s for residential development, its value goes up exponentially.” So they spiked their opposition and got the residential zoning.

You could argue that was a dirty deal. Or you could argue that by doing it, even before Hudson Yards, you had development right along the High Line. All those buildings are new. They didn’t exist before.

Covering crime and mob-related activities can get dangerous. Bagli remembers covering shady characters from Florida to New York.

I was writing about art theft in New York. I had friends who knew the mob, the Genovese family, I wasn’t going to compete with that. And the art world is exotic and interesting. I wrote about this gang getting into art theft—they went from electronics to art. They would steal Monte Carlo SS’s. They had police radios. Once they stole a cab, parked it at the southeast corner of Central Park, and phoned it in to 19th precinct and said, ‘Someone robbed a cabbie and the guy fled into Central Park and the cabbie went after him.’ The police got there and there’s a cab with the door open and the engine running. They’re looking around. That was a distraction. The thieves drive a stolen car through Jindo Furs and steal half million worth of furs. They know where the police are because they’re tuned into the 19th precinct. And they’re out of there.

I got onto this and at the time New York was one of two cities in the country with an art cop. They grew their hair long and dressed in black after a while. The other was Los Angeles. I started writing about this guy and I knew a lot about him and I knew they were close to turning him. They turned a driver, a wheelman. They get arrested and they’re in court and I have a big story that comes out their first day in court.

I walk into the Queens courthouse and I’m the only civilian there. Everyone else is either supporters of the bad guys or prosecutors. Two of the defendants come to me. I had written about some scam they and their mother had done. This is like a line out a movie: “Write anything you want about me. Don’t write about my mother.” Over time I became friendly with the leader of the gang. I’d go to the federal lockup every couple of weeks. I wanted to write a book about it. It’s made for a movie. This guy led the gang, even the night that they were arrested he told the wheelman the customary thing, which was, “We’re going to have to work tonight.” Which means there was a job but he was smart enough not to tell everybody where the job was. So the cops are staked out at two places in Manhattan…

He scared the hell out of my wife when he called us at home. She was less scared when Trump called and threatened to sue me.

And then there was the story of the trailer-park murder in Florida…

When I was in Florida, there was a case with a high school student and mother were arrested. The allegation was they killed the father. The father was an asshole who slept with his daughter and had a kid. They were in the woods at a trailer. They must have had an argument and he said, “I’m getting tired of you, the baby’s next.” He goes to sleep and she shoots him between the eyes. They bury him. Nobody knows about it for a year.

One night I’m meeting a source at a high school football field and someone pulls up in the lot and she recognizes them and so she runs. I go back to my car and he follows me. My heart was beating a little faster. I drove around and he kept following me. He wouldn’t get off my tail. I pulled into a stranger’s driveway and he sat behind me for a while before he finally drove off. I didn’t want him to know who I was because I didn’t want to put her in jeopardy.

A popular perception is that mobsters and criminals will leave reporters along as long as they get the facts out—so the mobsters know what others know.

I don’t know if that holds true. Jerry Capeci wrote about the mob for years for the Daily News and he has a site called ganglandnews.com and they all know Jerry. As long as he writes a straight story and he’s got it right, what are they going to do? But when the crack wars were going on in New York, I don’t know if some 16-year-old with a mag 10 had a code of honor that I’m not gonna shoot that guy. I wouldn’t count on that.

The writer’s ultimate job is to attract and hold the reader’s attention. Bagli praised Mark Singer for his ability to do that with the elusive topic of magic.

Singer wrote an article in The New Yorker about a magician named Ricky Jay. This article was brilliant. How do you make that really work? Magic’s a visual thing. He opened with a scene where he’s at a house party and they’re sitting around and he’s doing card tricks and he’s getting razzed and he slams the cards down and a card appeared in a bottle. I was mesmerized. I want to know more. It’s a brilliant piece of writing. It draws you in. It’s a difficult thing to write about.

I’m sure he wrote those scenes over and over till he got them right. You think: “Would my sister or mother or aunt want to ready this story?”

Writing long-form narrative—especially books—requires finding two or three compelling characters to “hang” the whole story and complex issues.

A while ago I was approached about writing a book about rebuilding downtown after 9/11. If I write a book that a lot of people will read, how do I do it? Who do you unfold the story around? Only a few people were there from 2001 to 2016, and I sure didn’t want to do it around Larry Silverstein.

To write a compelling book about rebuilding, you want to unfold it around something. After 9/11, the elite in real estate and politics were meeting off the record to say what should we do downtown. But there were also people who lost family members and they wanted a memorial. But residents didn’t want to walk past a cemetery all the time. Planners said lets bring back the street grid like before it was a superblock. I could write about the meetings and treachery and double dealing but you gotta sustain the story. How?

You have to ask who is my audience and what do they want to know? What are the assumptions they have?

Before you go . . .

• Like this content? For more posts on writing, visit the Elements of Writing Blog. Check out the posts on Storytelling, Writing Mechanics, Analysis, and Writers on Writing.

• For a monthly newsletter, chock full of hacks, interviews, and writing opportunities, sign up here.

• To transform writing in your organization, with in-person or online seminars, email us here for a free consultation.