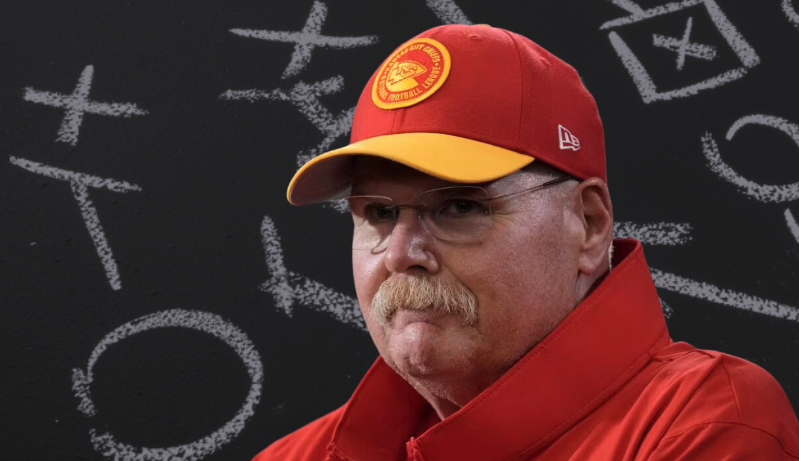

Behold the genius of Andy Reid.

As the head coach of the Philadelphia Eagles in a game against the New Orleans Saints in 2012, Reid had one of his players, Riley Cooper, lie down in the end zone for a kickoff.

Lie. Down.

The Saints thought they the Eagles had just 10 players on the field. They did not notice Cooper. When Brandon Boykin caught the ball, Cooper jumped up. Boykin threw a lateral pass to Cooper, who ran 93 yards for a touchdown.

Alas, the referee called back the play. Boykin’s pass went forward, so the ball got brought back to the 3 yard line.

Alas, the referee called back the play. Boykin’s pass went forward, so the ball got brought back to the 3 yard line.But talk about a clever pay, which caught the opposition off guard and had the potential to change the game.

Andy Reid is one of the most successful coaches in football history. He is the only coach to win 100 games with two separate teams. His Kansas City Chiefs have won the AFC West for eight straight years. After winning the 2024 Taylor Swift game, the Chiefs have also won three Super Bowl championships.

Reid’s secret is creativity, as Rodger Sherman explains in The Ringer:

Reid will invent strange new football ideas unlike anything that has been seen before—or at least not in the past few decades—and run them in the biggest moments of a season. And while his trick plays may appear like cockamamie inventions of a football mad scientist, they often take advantage of the unique strengths and talents of his superstar players. They are gimmicks and yet functional. “If you practice them long enough, they aren’t trick plays,” Reid said when I asked about his trick plays on Monday night, “they’re just plays.”

How does he come up with these plays? Like most coaches these days, Reid thinks about football all day and all night. At the highest levels of pro and college ball, coaches much give their lives over to the game. They arrive at the stadium early and stay late, every day. Some of them sleep at the stadium. With their team of associate coaches, they work on every facet of the game with their players during the week.

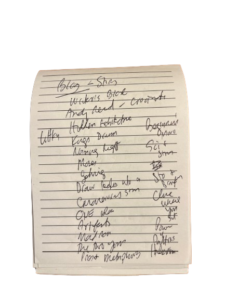

Wherever he goes — driving, eating at a restaurant, even sleeping — Reid carries a stack of index cards. As he turns over plays in his restless, football-obsessed mind, he frequently has eureka moments: “What if we…?” And when these ideas come to him, he writes them down.

In a profile of Reid in The New York Times Magazine, Michael Sokolove notes:

The index cards he always keeps with him spent the nights within easy reach because he never knows when he’ll think of a new play and want to draw it up. I wondered if plays ever come to him in his dreams. “I don’t sleep enough to dream,” he said.

Over the years Reid has gathered a massive collection of plays, many tried-and-true but others different and even bizarre. This collection is, in essence, a blueprint for the whole organization, as Sokolove notes:

What the best N.F.L. coaches have in common, Banner told me, is that they’re “so detail-oriented they even annoy everyone around them.” Reid aced the interview the moment he showed up with a thick notebook he had been keeping for years. It was filled with his meticulously logged plans for all the things he would do if he ever became an N.F.L. head coach.

Think about this. Creativity does not come in magical bursts of eureka moments. It is the deliberate, careful, disciplined gathering of half-developed ideas–and then the deliberate, careful, disciplined processing of those ideas.

Sustained effort, not magic.

Reid’s obsessive genius offers two lesson for writers:

- Always take a notebook, wherever you go. Your mind is restless and more powerful than you might know. Your subconscious is busy around the clock–and far more creative than your conscious mind. Your subconscious makes connections our conscious mind could never make. Your job is to be ready to capture all the ideas that come to you. You will almost never remember great ideas unless you write them down.

- Process the scribblings from your notebook. Other coaches and players say that, when they come to the stadium, Reid is already there. He’s transferring his scribblings from his notebooks to whiteboards. Later that day, he’ll review his clever ideas with his coaching staff. It’s not enough to capture stray thoughts, 24/7. You also need to process them, so that you can turn them into something useful.

You need to follow this process. Wherever you co, carry notecards. Whenever you have an idea — a fragment of dialogue, an idea for a character or conflict, a way of describing an idea, whatever — you need to capture it. Then you need to process and store your ideas so that they will be available when you need them.