The idea of genre can be a touchy topic among writers.

“Don’t classify me, read me,” Carlos Fuentes groused. “I’m a writer, not a genre.”

Genre refers to a type of story–the kinds of characters, problems, places, and conflict you can expect to encounter. People look for different things in stories–and when they don’t find it, they get angry. In that sense (like a brand in business), a genre is a promise. When you buy a detective story, you expect to see a smart loner systematically figure out who had the motive, means, and opportunity to commit a crime–confronted by a cunning opponent who matches him at every turn, until the very end.

Genre refers to a type of story–the kinds of characters, problems, places, and conflict you can expect to encounter. People look for different things in stories–and when they don’t find it, they get angry. In that sense (like a brand in business), a genre is a promise. When you buy a detective story, you expect to see a smart loner systematically figure out who had the motive, means, and opportunity to commit a crime–confronted by a cunning opponent who matches him at every turn, until the very end.

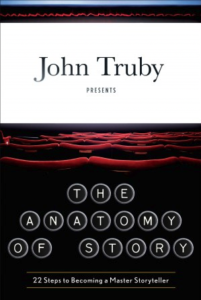

But as John Truby says in his brilliant new book, The Anatomy of Genres, a genre is not just a familiar way of living in the world of stories. It is a system. Any system–from the biological system of the body or the internal combustion engine of a car–succeeds only when each of its component parts performs its job and contributes to the larger process in a reliable way.

But as John Truby says in his brilliant new book, The Anatomy of Genres, a genre is not just a familiar way of living in the world of stories. It is a system. Any system–from the biological system of the body or the internal combustion engine of a car–succeeds only when each of its component parts performs its job and contributes to the larger process in a reliable way.

(To purchase The Anatomy of Genres, go to anatomyofgenres.com. For story courses and story software, go to truby.com.)

Truby lists 14 genres, in the following order: Horror, Action, Myth, Memoir, Coming of Age, Science Fiction, Crime, Comedy, Western, Gangster, Fantasy, Thriller, Detective, and Love Story. They move from the most primal issue (death) to the most transcendent (connection).

Truby offers two essential rules for genre writing:

- Each story must use 15 to 20 specific beats, or plot events, that fit its genre. When they’re missing, the reader senses a kind of void. Storytellers who think they can reinvent narrative–who resist the conventions of genre–are in for a rude awakening. You need to deliver what people expect when they pick a story. (For an overview of the beats in all genres, go here.)

- Every story needs to transcend its genre by offering something unpredictable and by using two or three other genres in supporting roles. A Sci Fi story can have elements of the Myth and Love Story genres, for example. Why the need for multiple genres? Modern people are surrounded by stories and get bored with overly familiar genre techniques. They need something extra to spritz the experience.

Truby’s work is primarily a guide for storytellers. But it is also a rumination of the role of stories in human life. Stories are not just accounts of people (or other creatures) doing things in an entertaining and meaningful way. Stories don’t just help us to “make sense” of life; they are not, as Joan Didion once said, “the imposition of a narrative line upon disparate images” we experience in life. Stories are not just about life; they are life. We could no more “separate” ourselves from the stories we tell and consume than we could separate the heart or the lungs from the body.

Why does that matter? Because the truest stories don’t just follow genre conventions. They tap something ineffable about human experience. That, ironically, is why the conventions matter so much. When we get them right, we are now free to discover the truths that lie deep in our minds and hearts and to somehow get them onto paper. Rules don’t restrict creativity but enable it.

To explore these issues, I talked with John Truby about his new book. An edited transcript of our talk follows.

How did The Anatomy of Genres come about?

I have taught writers for over 30 years. At times, when I talk with writers about what I do, they say, “I know all about story because I use the three-act structure or The Hero’s Journey or Save the Cat and they think that’s all they need. These approaches are fine for beginners, but they have very few practical story techniques—and almost nothing that can tell you how to write at the professional level. We’re talking about being in the top 1 percent of writers.

For me, genres are the highest form of knowledge because they tell us how the human mind works.

When I wrote my first book, The Anatomy of Story, my goal was to include all the professional story techniques a writer would need to write a bestselling novel or a hit screenplay. But the one subject it does not cover, which is the key to writing a hit film or novel, is how to write the different genres that make up 99 percent of popular storytelling today.

When I wrote my first book, The Anatomy of Story, my goal was to include all the professional story techniques a writer would need to write a bestselling novel or a hit screenplay. But the one subject it does not cover, which is the key to writing a hit film or novel, is how to write the different genres that make up 99 percent of popular storytelling today.

What about genres that makes them so important?

The answer is expressed in the subtitle: How Story Forms Explain the Way the World Works. We typically say that humans tell stories, but I believe it’s much deeper than that. Humans are stories. From birth, our mind creates our first story, and it’s the story of me. And from then on, everything I see and understand is a form of story.

Genres are different types of stories. Therefore, each genre gives us a different portal into how the world works and a different recipe for how to live successfully. For example, Horror says we live our best life when we confront our death and make amends for our sins. Fantasy says we succeed by making life itself a work of art. Each of the 14 major genres has a different approach to how to live.

If you want to be a successful storyteller, you have to express the deeper life philosophy through the plot of that genre. And frankly, most writers don’t do that.

Is it safe to say that the fundamental human problem is that we’re all going to die? Do the genres simply have a different answer to that question?

Absolutely. Horror is the first genre I explore because it deals with that question directly. It’s about how do you face your own inevitable demise. That’s something that nobody wants to face. In fact, nobody really believes it’s going to happen to them. All genres are about how to live a good life in this limited time that we have. Each genre gives a different recipe for how to do that: You will live a fulfilling life if you do X.

The genres each look at different aspects of life. Together, they add up to a comprehensive approach to understanding life.

All 14 genres not only have a very powerful and valid life philosophy; all of them are necessary for a fully rich life.

If you sequence the genres in a certain way, you get a kind of ladder of enlightenment. That’s why I start with Horror and Action at the base level and then move all the way up to the highest levels, which are Fantasy, Detective, and Love.

You could make a parallel with genres and archetypes. Archetypes show the different kinds of people in the world—and they reflect the tendencies that we all have within our own selves.

That’s absolutely right. But genres are much bigger than archetypes in terms of what they pull together into one system. The power of genres comes from the fact that they are based on the major activities of life. For example, Crime is about morality. The Gangster story is about business and politics. Memoir is about creating the self. Fantasy is about the art of living. Love is about how to live a happy life. The question is, how will we do that?

Tolstoy asked: “How, then, shall we live?” Each genre answers that question in a different way.

Exactly. And, you know, it is part of how I wrote each genre chapter. At the beginning of each chapter, I talk about each genre’s mind/action view. By that I mean, each genre expresses a unique way of thinking about the world, and each one shows how to have success, and that is the genre’s theme. Each genre combines the action side and the mind side. That makes it all-encompassing in terms of how to live.

So what are these genres about more specifically?

Horror is really about religion. Action is about success. Myth covers the life process. Memoir and Coming of Age are about creating the self. Science Fiction is about science, society, and culture—that’s why it has the biggest scope of all the genres. Crime is about morality and justice. Comedy is about manners and morals. The Western is about the rise and fall of civilization. Gangster is about the corruption of business and politics. Fantasy is the art of living. Detective and Thriller are about the mind and truth. And Love is about the art of happiness.

You don’t get any deeper or more expansive than that. And when you put all those together, you cover everything human beings do.

The sequence of genres could be arranged along Aristotle’s narrative arc, from the early basic challenge of survival to the ultimate development of the heart.

In my mind Aristotle is probably the greatest philosopher in history. Yeah, he was wrong about certain scientific things. But no philosopher contributed more important work in every major category of philosophy. He begins with metaphysics, with the process of becoming. And that’s what a story is.

My gripe with Aristotle’s Poetics is that it doesn’t give enough practical steps about how to tell a story. That’s one of the reasons I wrote The Anatomy of Story. And that’s why I wrote The Anatomy of Genres—to give writers the detailed, specific techniques they need to write a professional-level story.

We are not only a storytelling species, but also a summarizing, synthesizing, simplifying species. So one of the challenges of being a good storyteller is avoiding too many summary statements and describing specific people, places, and events in detail.

Yeah, it is. In my writing workshops, students often say, “Well, generally, this is going to happen.” But that’s not going to cut it. You need very specific actions. If you’re writing a Detective story, you’ve got to have a very specific clue that gives you a very specific reveal and then you’ve got to build on that. A great story is a series of causal links. You’ve got to be specific about what each person is doing at each moment.

Imagine how bad The Godfather would be if Mario Puzo said, “There was a big wedding in the family and a good time was had by all as Don Corleone did some business on the side.”

Exactly. And that’s the way most writers would do it. And that’s why you’ve got to be so precise in the sequence of actions you put in the story.

In any genre, there are 15 to 20 major plot beats unique to that form. They must be in that story or you’re not doing your job and the reader will be very unhappy with you. Plot is the most challenging thing for writers because they think in terms of individual moments in the story. No, it’s all about stringing together a sequence of events—which are driven by the opponent.

How do you do that?

Start with the opponent’s plan to defeat the hero. That might be the most important technique for creating a plot.

Take the Love genre. Realistically, a love story should take about 10 minutes. You’ve got two people who are attracted to each other. The rest is negotiation. But for a movie, it’s got to last at least 90 minutes. So how do you do that? Start with the opponent—and in a love story, the main opponent is the object of desire.

Back to the importance of action—lots and lots of beats. How do all these beats hang together?

Each individual beat means nothing without being part of 15 to 20 other beats. The beats in all the genres have been worked out in great detail over decades, sometimes centuries or even thousands of years. So you need to know the sequence of 15 to 20 beats for the genre you’re writing in.

But the real key is how you transcend the genres. Otherwise, you’re telling the same story that everybody else in that genre is telling. You’ve got to tell your story in a unique way.

How do you do that?

It means executing the individual beats in a way that we haven’t seen before. More importantly, it means expressing the life philosophy through the plot beats. And that’s the area where writers go wrong. The most underestimated element of storytelling is theme. Writers are terrified of theme. They’ve heard the old rule that if you want to send a message send it Western Union. So, to avoid hitting the theme on the nose they avoid theme entirely. It’s one of the biggest mistakes you can make. You need to express theme under the surface, through the structure, through the plot beats. If you’re not expressing the life philosophy of that genre, you’re getting one-tenth of the power of your story.

Genre is often described as a promise to the reader. When you pick up a Western, you can rest assured that you will get all the elements that have always made you enjoy a Western. Likewise, the character’s expression of a life philosophy is another kind of promise.

That’s the promise that most writers don’t know. They know that genre is a plot system. What they don’t know is that it’s also a theme system. The challenge is to express the theme through a complex plot.

Are there some tricks to express the theme with action? Let’s try an example. Imagine a couple of friends playing pickup basketball and one of them is overly aggressive and the other one is focused on style. And the aggressive guy beats the style guy and says, “See, that’s your problem, you were too concerned about strutting around, so you lost.” So in this case, you could build the theme into the action and dialogue.

Yeah, but the dialogue should be minimal. The theme should be expressed through the action and structure. And that brings us to another point, which is that one of the ways you transcend the genre is to mix genres. You need to combine two, three, even four genres. Each genre has 15 to 25 plot beats. When you combine that with two or three genres, you separate yourself from the rest of the crowd.

If you just mashed together three genres, that could be a mess—and disorienting. Somehow, you need to control your use of the different genre beats.

If you don’t know how to mix genres, you get story chaos. That’s why you have to choose one genre to be the primary form. That provides your structure—your hero, your main opponent, the key desire line, and so on.

Then you grab the beats from the other genres and mix them in—but only when they work with the main genre. If the minor genres come into conflict with the main genre—and many do, since they’re different approaches to handling the same problem—you stick with the plot beat of the major genre.

So your main genre is your North Star. You use the other genre beats when they strengthen the thrust of the main genre.

Exactly. And there are a lot of things that determine the main thrust of your story. But the most important one is the hero’s goal. And so whatever you can attach to that spine, to that goal, you want to use that.

Can you give an example of a great story that uses a major genre but is also supported by other genres?

In The Godfather, Mario Puzo combined Gangster with Fairy Tale and Myth. It’s actually three story forms blended together, with the structure revolving around the father and his three sons. That’s a Fairy Tale technique: the three sons. Each son has a different set of traits and characteristics. You see how each one responds and only the third one has the right combination of traits to be a successful godfather. If you were writing a typical gangster story, you’re not going to come up with The Godfather. It’s unique to Mario Puzo.

Francis Ford Coppola could not have created a movie like The Godfather without the massive level of detail in the novel. The worst writing mistakes get made—the worst cliches happen, the worst stretches of boredom happen—when you don’t have enough raw materials. You need a pile of details and moments and possibilities to create a great story.

That’s why Hollywood prefers to start with a novel, because it’s a lot easier to condense a novel and get a really dense plot in a film. When we think of The Godfather book, people think of it as just pulp fiction. No, this is a great book. This thing is brilliant. And I have learned so many lessons of storytelling from reading that book and watching that film.

You’ve got to have specific details at every level of the story. Only when you have those kind of details can you then sequence them together into an overall story, where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Many writers simply do not understand the connection between the detail level and the master scheme level.

Do you have any favorite genres?

I love all these genres. In writing this book, I gained tremendous love and respect for the genres that I didn’t really care about. Each genre gives you this portal to different activities of life. But even though I love all the genres, the ones that I love the most are the Western and the gangster.

The Western is about the rise of the American Dream and Gangster is about the corruption of the American Dream. The Western is completely inaccurate historically, but it’s not about real history. It’s the American Creation Myth. The Gangster is the best expression of how the real world works now because it focuses on the corruption of business and politics.

The Gangster form is the closest genre to the Great American Novel, which explores how America has failed to meet the ideals expressed in its creation documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The Great Gatsby is a transcendent Gangster story. Mad Men is basically a modern-day Great Gatsby. Both main characters create a new identity from a lie. They both express the basic American ethic that you can be whoever you want to be.

Mad Men, by the way, is one of the five best TV dramas ever made—just a massive work of art, one of the great American epics ever written.

Mad Men’s first episode tells you everything you’re going to experience in the show. Matthew Weiner knew where he was going to go. He knew the final scene of the series the whole time.

That’s one of the keys to writing a transcendent work in TV—having a sense of the overall track of the main character’s development from the very beginning. Breaking Bad was the same way.

So your two favorite genres are the Western and Gangster. They both explore the American Dream. If you were French, would they still be your favorite genres?

I grew up with the Western, which expressed that whole conception of the American ethic, which is incredibly positive and empowering. When I was a teenager, I encountered the four great anti-Westerns: The Wild Bunch, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and Once Upon a Time in the West. They are the Gangster versions of the Western. They are about the fall of the American Dream.

Seeing these films was a major turning point in terms of my understanding of the potential, the philosophical power, you could have from a Hollywood feature film.

Movies do something that no other art form can do, which is they get us out of the utter wordiness of life. We have the tendency anyway to overly simplify things. Images get us to be in the moment.

Images are obviously central to modern storytelling. But one of my bugaboos is the idea that that film is a visual medium. Yeah, it is. We see a screen with images. But that’s not what people respond to. Film is a story medium. This is why I find the idea of the auteur theory one of the dumbest things ever. No, film is created by the writer. It’s the writer creating the character, the plot, the structure, the theme, the symbols, the dialogue, all the stuff that the audience is responding to.

If film was just a visual medium, we should say that silent film is the greatest film we’ve ever seen. But there’s a real advantage to talk. That’s why talkies got to be so popular so fast. People also say, well, you got to express ideas visually. Yeah, well, that’s true of any story: “show don’t tell.”

Look at Casablanca. If we were judging it based on the visuals, we would say that thing’s terrible. But it has probably the greatest dialogue in the history of film. When people say a picture is worth a thousand words, I always say a word is worth a thousand pictures. Words are what give you texture. Words are how we know that that person is a unique from everyone else.

Truman Capote once said that “all literature is gossip.” People are whispering about somebody else, often in a very judgmental and a prurient way, in secret. In that sense, the best stories feel like eavesdropping. You weren’t supposed to see Don Corleone in that room—that’s a private thing and you weren’t invited. You often say that stories are portals into different worlds, where you have no business being.

Right, the portal gets us past the public facade. Stories are about the private, where people have the most painful moments and experiences with each other. This is something we don’t talk about in public because it’s often painful and embarrassing. But that’s what stories allow us to do.

We all have secrets. Because they’re secrets, we don’t want anybody else to know what they are. But stories can get at them. If stories were only about what people do in public, they would really be boring. So in a way, the best way to think of stories is they capture the things that nobody else wants to let you see.

So, shifting focus, I was wondering if you ever feel “storied out.”

It’s just the opposite. When I watch a movie, I am absolutely entranced—unless the writer screws up. That’s what breaks my suspension of disbelief. And then you’re out of the story. But when I see great storytelling, it’s a totally enriching experience. I’m fascinated by the techniques the writer used to get those effects and how they applied the technique to their particular story problem. And then how that illuminates the way life works and how the human mind tries to make its way within it.

I sometimes liken it to sports. Let’s say you watch football. If you don’t know much about football, it just looks like a mass of bodies jammed together, and they just do that up and down the field. That’s boring. But if you know what’s happening, you are literally able to see the details as they happen. You can see, oh, that right guard is pulling, the defensive end did a trick maneuver to get to the quarterback, et cetera. You get into what’s happening structurally, under the surface.

This is why my approach to story has always been about structure. What’s most fascinating is there’s the surface of what’s happening and there’s the deep structure of what’s really happening and why. It’s getting to the deep causes that I find absolutely fascinating. And the reasons for it happening are often very different than we really think.

Can I ask about our current political situation? We have all these performance artists running around, lying, avoiding issues, breaking the law. It’s really the Gangster stage of our development. And a lot of what these gangsters and liars are doing is creating fake stories. So the key thing about being able to put on your story analysis hat is that you’re able to see through that.

With the rise of information technology, the ability to divide image from reality has never been greater—which means the ability to lie has never been greater.

So how do you deal with it? What genre can help us to separate truth from lies?

To me it’s the Detective story. It’s about asking questions, looking at evidence and using methodology. We can never get the whole truth. But you can get to some degree of truth that is not a complete fabrication. And that’s why the detective form is so valuable. I consider it the most important modern genre. Few of us are action heroes. But we can all learn how to look for the truth. The detective story tells us how. Science itself is a detective story.

Robert Caro, the great biographer of Robert Moses and Lyndon Johnson, once said something to the effect of, “I don’t know what truth is but I do know what facts are. And facts can add up to some amazing insights.”

And it is something that everybody is responsible for. I don’t think people take nearly as much responsibility for it as they should. If we don’t do it, the larger system is going to collapse.

If we don’t take control of the detective narrative, if we don’t play our parts, so to speak, then you’re going to let the bad guys write their own horror stories, gangster stories, action stories and myths.

With the possible exception of the Love story, there’s no story form more important to our success, not to mention survival, than the Detective story.

Given the importance of the detective story, is there an ideal detective?

The model for the detective, and the most brilliant of all detectives, is of course Sherlock Holmes. He is one of the most influential, if not the most influential, character in modern storytelling.

But there’s no way I’m going to be able to meet somebody for the first time and know that he was in Afghanistan and that he’s a doctor, et cetera. So in terms of the detective’s fact-finding mission, is there another one? I was I was going to say Woodward and Bernstein …

Sherlock Holmes works from the ground up. It’s not just that he’s a genius. It’s his observations that help to solve the case.

Observations about the dog that didn’t bark in the night.

Right. Sherlock Holmes is the master of starting with the facts, starting with the clues, with the specific physical evidence, and then slowly but surely generating a larger theory, a larger story of what truly happened. And that is the methodology. We need to use methodology to get away from these divisive ideologies. Too many are so trapped by their own ideology, they can’t see basic facts.

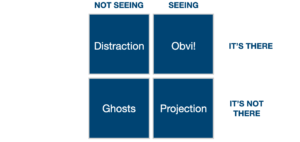

And looking is a very hard thing to do. Most of what I see, I’m actually constructing in my brain, based on my experiences and my predictions.

Absolutely right. One of the things that was so fun about writing the detective chapter was to look at all the things that prevent us from being able to see ourselves because of the ideology that we’ve created since childhood. Our stories allow us to see only certain things. Humans are pattern-making animals. But it amazes me how often the pattern people put together is complete nonsense.

We all have stories of our own lives and those stories are usually wrong. So the key, whether you’re a storyteller or reader or just a person trying to lead a decent life, is developing the ability to reject the stories that don’t actually pan out.

That’s what the Memoir genre does. In a memoir, you look back and see the story you created for yourself to help you survive. But those stories were full of errors. You created them when you were young. Or you were given them and you bought into it because it came from dad. So the great question of memoir is: How do you create a new story that allows you to have a better life in the future?

Before you go . . .

• Like this content? For more posts on writing, visit the Elements of Writing Blog. Check out the posts on Storytelling, Writing Mechanics, Analysis, and Writers on Writing.

• For a monthly newsletter, chock full of hacks, interviews, and writing opportunities, sign up here.

• To transform writing in your organization, with in-person or online seminars, email us here for a free consultation.

The exception proves the rule: Socrates, the hero who surrenders his life Plato’s dialogues, struggles with the brokenness of the Greek political elites.

The exception proves the rule: Socrates, the hero who surrenders his life Plato’s dialogues, struggles with the brokenness of the Greek political elites.

Kahneman, a psychologist who won the 2002 Nobel Prize for economics,

Kahneman, a psychologist who won the 2002 Nobel Prize for economics,

So what do you do when the faucet stays stopped up–or, even worse, when the words flow but they’re all terrible?

So what do you do when the faucet stays stopped up–or, even worse, when the words flow but they’re all terrible?

Fletcher, the author of the landmark work

Fletcher, the author of the landmark work

She grew up in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom when her family participated in the “back to the land” movement. As other Americans embraced the creature comforts and congestion of the suburbs, the Daloz family left to live independently among other naturalists, rebels, activists, and free lovers.

She grew up in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom when her family participated in the “back to the land” movement. As other Americans embraced the creature comforts and congestion of the suburbs, the Daloz family left to live independently among other naturalists, rebels, activists, and free lovers.

Readers sometimes get annoyed when they hear conversations about the story’s allegories or deeper message or hidden structure. Why can’t a story just be a story? Why do academics and gurus have to spoil the immersive experience of a story by breaking it down into patterns and pieces?

Readers sometimes get annoyed when they hear conversations about the story’s allegories or deeper message or hidden structure. Why can’t a story just be a story? Why do academics and gurus have to spoil the immersive experience of a story by breaking it down into patterns and pieces?

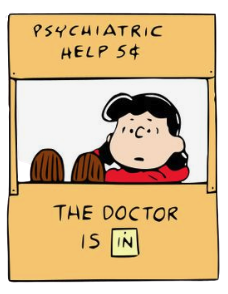

I first saw you outside the 72nd Street subway station in New York. Your popup table reminded me of Lucy’s setup on “Peanuts.” What made you think of turning writing and grammar into a public event? Is it even more than that— performance art, for example?

I first saw you outside the 72nd Street subway station in New York. Your popup table reminded me of Lucy’s setup on “Peanuts.” What made you think of turning writing and grammar into a public event? Is it even more than that— performance art, for example?

Seminars for Storytelling in Business provide the core skills for connecting with people inside and outside the organization.

Seminars for Storytelling in Business provide the core skills for connecting with people inside and outside the organization.