To succeed as a storyteller–or as a musician, architect, scientist, or other creative person–you must work within a specific genre.

The story genre provides the style, rules, and expectations for the tale. What kind of hero and other characters will we meet in the story? What kinds of settings, struggles, and values will we explore?

A genre is a promise: If you read this detective/romance/action/whatever story, you will get what you’re looking for.

In recent years, the idea of genre has spun out of control. One recent analysis posits thousands of kinds of stories. That’s way too many. That’s why I decided to create a simple framework for understanding genre.

How Genre Got Out of Control

Virtually every reader or movie-goer will recognize a dozen or so genres. Besides the overarching categories of Comedy and Tragedy, most people will recognize genres like Romance, Love, Western, Crime, Thriller, Gangster, Horror, Fantasy, Sci-Fi, and Memoir.

So far, so good.

So far, so good.

But in the age of the screen, people are overwhelmed with stories. Stories were once a means of standing back to observe reality; now stories are embedded into everything we do. As a result, we can bet bored with the standard sets of genres. Detective, ho hum. Horror, yawn. Romance, (eye roll). Gangster, so what?

Storytellers these days have to be ever more clever, so they stretch existing conventions of storytelling (e.g., Memento, Life’s Arrow) and mix-and-match different genres (e.g., The Godfather and The Sopranos as family/gangster tales). Think of the opening montage of The Player. After hearing a pitch for a movie about a TV star who gets lost on a safari, the producer says: “It’s like The Gods Must Be Crazy except the coke bottle is an actress.” “Right!” the writer says. “It’s Out of Africa meets Pretty Woman.”

Eric R. Williams, a story and gaming guru based at Ohio University, has developed a rigorous system with three basic levels: Super-Genres (11 categories), Macro-Genres (50 story contexts), and Micro-Genres (199 specific story details). By mixing and matching these genre elements, Williams says we can come up with 187,816,200 distinct story types.*

Has the proliferation of genres–and the constant stream of genre theories–made the craft of storytelling overwhelming? Where is Occam when we need him?

Genre, Simplified

That’s why I decided to create The Simplest Genre System Ever.

I began with a simple idea: All stories are either comedies or tragedies. Comedies are struggles (often but not always ha-ha funny) that end with the hero getting what she wants. Tragedies are struggles that end badly, with the hero not only losing but often destroyed. That hero might gain a new understanding of life, but comes too late to save her.

But that’s just a starting point. To tell a good story, we need to answer two questions:

- In what kind of setting does the story take place, ranging from someplace close to home to a faraway locale?

- What kind of quest does the story depict, ranging from an inner, psychological quest to an outward, more material or transactional quest?

That’s what genre is all about. It’s about offering a distinctive kind of story, based on the setting and quest.

Plotting Genre

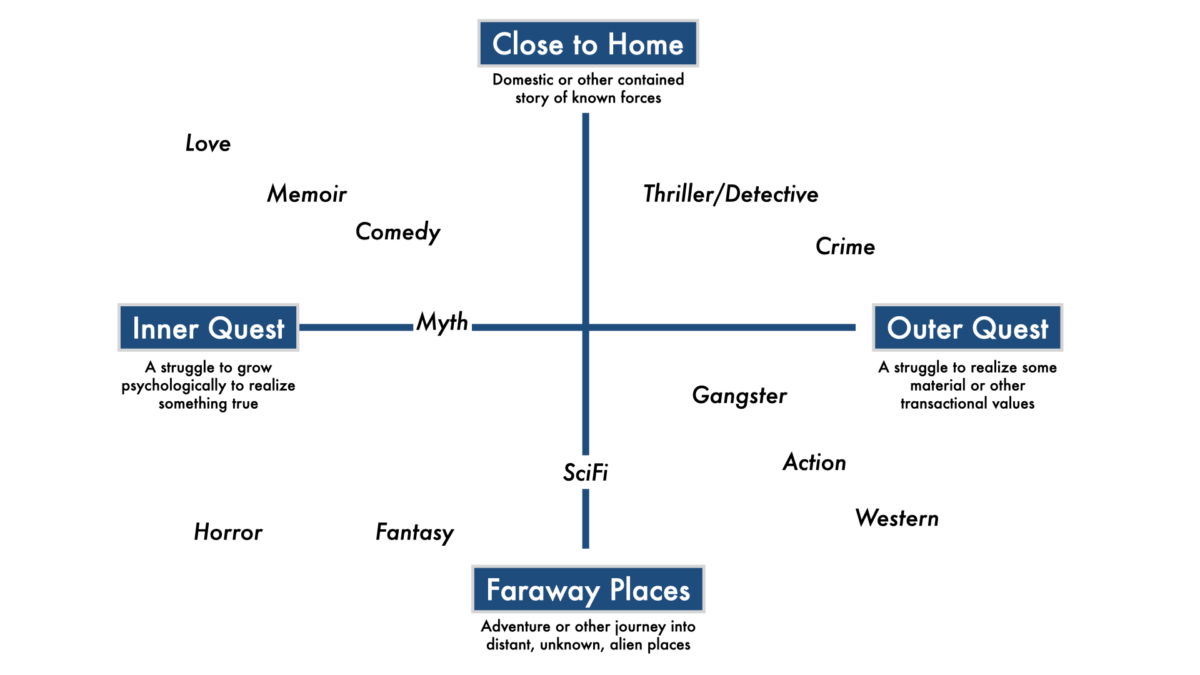

Take a look at the four-cell chart on the top of the page. With this format, I have arranged the genres that John Truby describes in his master work, The Anatomy of Genres. Let’s look at these genres, quadrant by quadrant:

Inner Quest/Close to Home: These stories play out on familiar ground of the heart.

- Love stories almost all take place close to home and always awaken the heart. For example: Romeo and Juliet, Poldark, Wuthering Heights, Sleepless in Seattle.

- Memoirs are even more interior in some ways, often depicting the Hero’s battle with herself to overcome the problems of living close to other people. Think: Running With Scissors, Listening to Prozac, Educated.

- Ha-ha comedies also tend to be close to home, since they rely on misunderstandings revealed by everyday fumbles. Such as: Duck Soup, Groundhog Day, Airplane!

Inner Quest/Faraway Place: These stories also plumb the mysteries of the heart but take place in strange places.

- Horror stories often take place in the home, but also take place in mysterious and creepy woods, city streets, and even other worlds. For example: The Exorcist, Dracula, and Frankenstein.

- Fantasy tales are set in whole worlds of invention and unreality. Think of the Harry Potter stories, The Chronicles of Narnia, The Game of Thrones, or The Hobbitt. Or if you’re old-fashioned, think of the enchanted forest of Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

- By traveling to whole new times and places–and even different dimensions of being–sci-fi goes deep on intimate or emotional issues. Think: Star Wars, The Bladerunner, 2001.

Outer Quest/Close to Home: In some takes, people are emotionally dead and battle exterior challenges.

- Crime stories are all about solving problems, often with domestic characters, highlighting the power of logic and persistence. See: Anatomy of a Fall, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and Thelma and Louise.

- Thriller and detective tales do the same, but with the heightened tension of impending catastrophe. Think of Hitchcock’s oeuvre and the gumshoe tales of Dashiell Hammett and Arthur Conan Doyle.

Outer Quest/Faraway Place: In these takes, the force and violence rules the untamed frontiers of human existence.

- Action stories show characters clashing to the death, usually far from any domestic concerns. The goal is to vanquish a foe more than to find any inner child. Think Stallone and Ah-nold.

- Westerns show the clashes of the good guys (sheriffs, cowboys, ranchers) trying to create order out of disorder–or to survive or thrive in that disorder. Bonds are based on opportunistic calculations, not emotional commitments. Think of Unforgiven, Tombstone, and Killers of the Flower Moon. Going back further, see Duke Wayne’s classics and James Stewart in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance.

- Gangster stories bring the Western to the anarchy of city streets, where order is more dependent on a balance of power than a common ethos. For example: A Bronx Tale, Once Upon a Time in America, and Good Fellas.

This is just a starting point. We might debate the genres organized on the four-cell chart. But it offers a simple starting point for understanding the concept of genre. Ultimately, it’s up to storytellers to find the right place on that chart.

*That reminds me of Lewis Carroll’s story “Sylvie and Bruno Concluded,” in which people devise a map with “the scale of a mile to the mile.” It kind of defeats the purpose, no?