The first time I met Bob Moses, I was sitting in a lecture hall with a group of more than 100 puzzled students at Holy Cross College.

The college invited Moses to speak to the First-Year Program. In that program, students in a wide range of classes–philosophy, history, theater, math, physics, the languages–grappled with a common question. The question that year was: “In a world bound by convention, how then shall we live?”

The college invited Moses to speak to the First-Year Program. In that program, students in a wide range of classes–philosophy, history, theater, math, physics, the languages–grappled with a common question. The question that year was: “In a world bound by convention, how then shall we live?”

Robert Parris Moses, who died on July 25 at the age of 86, grappled with both sides of that question his whole life.

The convention ruling black lives then was not just oppressive and violent, but intellectually and emotionally crippling as well: Either accept the idea of white superiority, living submissively with your own kind in a segregated and unequal world, or face vicious retribution.

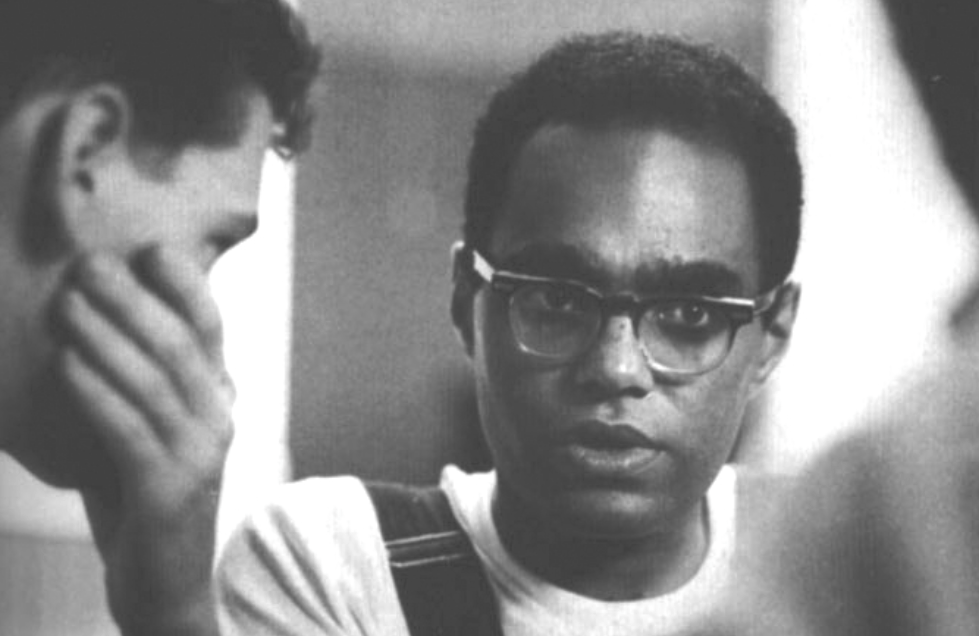

Moses was awakened in 1960. Teaching at a prep school in the Bronx, the 25-year-old Moses followed the exploits of the student sit-in movement with awe.

“Before, the Negro in the South had always looked on the defensive, cringing,” he later said. “This time they were taking the initiative. They were kids my age, and I knew this had something to do with my own life.”

Bob Moses went to Mississippi, the most violent of all the old Confederate states, and took up the challenge. Joining the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he worked to register voters in the isolated towns where blacks had never been encouraged to speak or act for themselves. White mobs attacked him and cops arrested him. In Greenwood, sitting in the passenger seat of a car, bullets missed him but hit the driver and he had to steer the car to safety. In Liberty, someone attacked him with a knife as he was leading a small group to register at a courthouse. Bloodied, he was arrested; when he pressed charges, his assailant was acquitted by an all-white jury on the grounds that he had provoked the attack by assuming a threatening stance.

In 1964 Moses was the leader of Mississippi Freedom Summer, perhaps the most audacious moment of the civil rights movement. Hundreds of white students came into the state to register voters and lead freedom schools. The campaign led to countless attacks, including the murders of James Cheney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman, which put a glaring spotlight on violence in the system of segregation. Later, Congress passed and President Lyndon Johnson signed the landmark Civil Rights Act of 1964. Moses also helped to organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a democratically elected slate of delegates that demanded to be seated at the party’s 1964 national convention in Atlantic City. They lost that battle–the convention seated the traditional slate of segregationists–but that challenge transformed the Democratic Party. Before, it accepted segregation; after, it rejected segregation.

Back to that moment at Holy Cross.

Moses stood in front of the lecture hall and described a lynching in which (not uncommonly) crowds gathered to watch and celebrate, even photographing themselves near the hanged, charred corpse. He read a letter by a witness, who described the moment in detail, without a trace of understanding or care.

Moses asked students for a response and then fell silent.

Confused, students shifted in their seats. Their eyes darted to each other and to their professors. They expected (as did we all) an inspiring account of heroic exploits. Moses was defying this convention. Finally, the long, awkward silence broke and students began to talk. Moses stood and watched and listened. Some students later felt disappointed that they did not get their expected burst of inspiration; others walked out transformed. Moses had given them the ultimate lesson: You are responsible. You can’t wait on others. You need to find your own voice. In your own way, you need to face the brutality of this world.

That’s how he operated in the movement. He was the quietest of all movement leaders. Taylor Branch, Martin Luther King’s Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer, said: “Moses pioneered an alternative style of leadership from the princely church leader that King epitomized. … He is really the father of grass-roots organizing — not the Moses summoning his people on the mountaintop as King did but, ironically, the anti-Moses, going door to door, listening to people, letting them lead.”

Moses understood, as activists often forget, that the greatest resource in any struggle is the people themselves. They have the intelligence and strength to resist; the organizer’s job is to help them understand, develop, and exercise their own power. The greatest leaders are themselves servants who help others to become leaders.

In Mississippi, Moses found activists in isolated hamlets by bouncing a ball. He knew that blacks had been terrorized for generations and faced abuse if they stood up for their rights. If he approached them cold—knocking on doors, talking with them in stores or fields or churches—they might be too scared to talk. So he stood on street corners and bounced a ball. That attracted a crowd of kids. Then, inevitably, the ball got away. “Before long,” Moses explained, “it runs under someone’s porch and then you meet the adults.’’

If King was the Moses of the movement, as Taylor Branch said, Moses was the King of the movement in Mississippi. He was revered because he knew how to listen and guide people to become their best selves. In fact, hearing him often took great effort. He spoke so softly that you had to lean in and really focus on what he was saying. Since he was not nearly as voluble as others, what he said really mattered.

I met Moses again as I was researching my book Nobody Turn Me Around: A People’s History of the 1963 March on Washington. We met in Cambridge, where he was leading the Algebra Project, an effort to bring math literacy to blacks and poor people everywhere. He talked so softly that when I got home, I had to play the tape on a speaker, crank up the volume, and listen intently.

That conversation covered all the familiar topics. But to me, the most telling moment came when I minimized the importance of the Civil Rights Act of 1957. The law established the civil rights division in the Justice Department and empowered federal officials to prosecute people who conspired to deny others’ right to vote. But the law did nothing to open schools or public accommodations or voting booths to black Americans.

Moses corrected me. That law made a bolder civil rights movement possible, he said, by giving activists a “crawl space” in the government. If a later president was sympathetic to civil rights, the activists could develop relations with the civil rights people in the DOJ. And so when John Kennedy became president, he sent John Doar and John Siegenthaler to DOJ. They offered critical help to the movement. They coordinated activities, shared intelligence, and developed a trust that made better things possible.

The civil rights movement required a wide range of heroes. The movement needed the audacity and grit of A. Philip Randolph, the nonviolent cunning of Bayard Rustin, the soul of Martin King, the egalitarian ways of Ella Baker, the intellectual rigor of James Lawson, the impatience of Stokely Carmichael, the love of Daisy Bates, the stubbornness of Fannie Lou Hamer, and the quiet servant leadership of Bob Moses–and so much more. In the story of civil rights, the idea of “a hero” is nonsensical. Countless heroes, most of them quietly working in the “crawl spaces” of the society that oppressed them, were necessary for success.

They were then, they are now.