You are in grad school, working for your M.A. or a Ph.D.

To succeed, you need to write a dissertation or thesis. This is a major project–50 pages or so of dense writing in the hard sciences, hundreds of pages in the humanities and social sciences. Chances are, you’ve never written anything that long. What do you do? How do you start? How do you pick a topic? How do you set goals and organize ideas? How do you write? How do you edit your drafts?

Most programs don’t offer much good advice. Where I went, I heard “Don’t get it don’t right–get it done” and “Say what you’re going to say, say it, and say you said it.” Not terribly helpful.

Most programs don’t offer much good advice. Where I went, I heard “Don’t get it don’t right–get it done” and “Say what you’re going to say, say it, and say you said it.” Not terribly helpful.

In this post, I show you ten simple strategies that you can use–starting right now–to get the project done faster than all your peers. The trick is to break the project into manageable pieces, follow the right sequence, and do at least something every day.

(The post is most relevant for work in the humanities and social sciences. But many of these tricks will be helpful for work in the hard sciences as well.)

Start by treating the project as a management challenge. Good managers set a clear goal goal (the whole) and keep track of all the pieces (the parts). In some ways, writing a thesis is no different than running a grocery store or coordinating a lab experiment. To succeed, you need to break projects down, work in a smart sequence, get clear and useful feedback, keep track of all raw materials, and make good final decisions.

And so, without further ado, ten simple tricks for managing your dissertation process.

1. Find a topic that intrigues you–then constantly narrow and expand that topic.

You will live with your topic, 24/7. You better love spending time exploring it.

Yes, love.

Some graduate students select a “practical” topic–one that’s limited, with lots of data, with a clear research question that (might) yield a clear answer. Their “practical” thinking might include the prospect of getting a publication. If you do all that and still find a “practical” topic rich enough to intrigue every single day, that’s great. Practical + Intriguing = Winner.

But do not talk yourself into a topic because your advisor or someone else thinks it makes sense. Sure, explore all reasonable possibilities. But if you feel dread in the pit of your stomach, be careful.

For sure, you need to be able to do the research. You can only write about a topic if you can get access to the data, lab experiments, archives, interview subjects, and so on, depending on your field. If you can’t get the raw materials, you can produce the final product. depending on your discipline, you’d also benefit from colleagues with whom you can share ideas and critiques.

But if you don’t love your topic, you won’t have the zest to do the research and struggle to make sense of it.

So here’s what you do: Make a list of a bunch of different topics, then check them out for their passion and practicality. Look for the sweet spot — the topics that both fascinate you and promise lots of access to information. If you get lots of data, you’ll love the project more than if you can’t find any data. And if you love a topic, you’ll be better at digging for data.

2. Focus, maniacally, on finding The One Idea.

Most dissertations start out as a “topic.” But they need to finish as an “idea.” That idea has to serve as the North Star for everything you discuss. (For a detailed blog post on this challenge, go here.)

Let me explain the distinction. When I began my research, my topic could be stated like this:

Almost every major league city in the U.S. is now facing pressure to build new stadiums and arenas for its teams. When teams threaten to leave unless they get their new palace, mayors and civic leaders cave in to their pressure. And so cities (with state and regional governments and authorities) are spending hundreds of millions to benefit private franchise owners.

That was fine–to start. But eventually, I had to find my ONE Idea. Here’s how I concluded:

In the battle over team location, leagues and their teams hold two advantages: (1) They are part of a monopoly and (2) They can move. They use these advantages to “steer” public dialogue. If everyone in the community got together to decide stadium proposals, they would usually lose. Why? Because they do not improve local economic development. But the sports industry’s unique traits allow them to steer and control the dialogue and bargaining. So they usually win.

The “topic” said: Something happening. The “idea” said: Here’s the one factor that determines the result.

3. Carry (and use) a cheap notebook wherever you go.

Every day, you have 50,000 to 70,000 thoughts. Most of those thoughts are trivial and fleeting. You are happy to brush them aside as soon as they arrive. But you might have (I’m guessing) 100 thought that are worth keeping and developing. Those ideas arrive, unbidden, as we sleep and shower, walk and drive, doodle in a meeting and sit in a lecture.

Unless you capture your ideas when the arrive, you almost always lose them. Some variant of the diea might pop back later, but you can’t count on it.

Notebooking ideas also helps you process them. By transferring an ideas from a shower “aha” moment to ink on paper, you begin to transform those ideas. One idea leads to another. One concept reminds you of another concept.

I suggest getting a cheap and flexible notebook. Too many people spend $20 on a

4. Outlines for dissertations: Yay or nay?

Usually, the first thing your advisor asks you to do is write an outline. Don’t! Outlines can be awful straitjackets that limit your research and creativity and keep you from breakthrough ideas.

Instead of an outline, keep a running list of problems and ideas you want to explore. You might want to keep that running tab on Evernote, some other notes app on your phone, or your cheap notebook from Staples. Whatever works.

At first, don’t try too hard to organize the ideas. Once you have 20 or so topics, you’ll want to cluster them into different categories. Fine. But don’t think of it as an outline or blueprint. It’s really just an extended log of ideas.

Don’t worry too much about separating Big Ideas from small ideas. They’re all important. My nephew did a dissertation at Cal-Berkeley on robotics. His Big Idea was that nature offers powerful lessons for designing the way robots move and perform actions. But to explain that idea, he had to give lots of definitions, describe the literature on animal movements, explain ideas about miniaturization and batteries, describe distinct coding challenges, and more. You need all kinds of ideas, big and small, to help you explain The One Idea.

Another point: You can’t always know what ideas are Big and which ones are small until you develop them. The Big Idea of my dissertation, many years ago, concerned the structure of dialogue in cities. That idea started out as a side note. As I got deeper into my research, I realized that it explained the whole issue. It started as a trivial aside and then became my Big Idea. Since you cannot know which ideas will bloom, gather them all. Don’t worry how important they might be until later in the process.

5. How do you organize your notes and research materials?

In many ways, an ambitious project is as much a management process as a creative process. Just as a supermarket manager manages the food deliveries, the departments and aisles, the equipment, the workers, and so on, you as a dissertation writer will manage your books and articles, notes and transcripts, lab results, spreadsheets and other data holders, videos, paper and electronic files, and, of course, fragments and drafts.

Your key tool is the folder, both paper and electronic. Into each folder, you can put all kinds of resources. To make it work, you need the right categories and sub-categories. In my work, I have two kinds of categories–topics and types of materials.

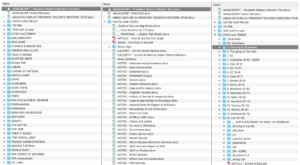

Take a look at the computer folders for my forthcoming book on Woodrow Wilson’s 1919 Western Tour for the League of Nations:

Click the image to get a careful look. The first column shows all of the major folders in the project. The second two columns show what’s in a couple of those folders.

It’s not always easy to figure out the best topics for the folders. They have to be as simple and intuitive as possible. You don;t really know what makes sense until you’ve gotten deep into the work. I renamed and reorganized the folders countless times. Every time, it gets easier to find what I want.

A good organization also makes it easy to get a gestalt view of the project. Any time I want to get a bird’s eye view of the project, I view my folders.

6. Understand the research challenge.

Some research will revolve around one kind of information. Research in biochemistry will revolve around lab work; research on literature will revolve around the text. But many research projects involve a wide range of research challenges. When I wrote Nobody Turn Me Around, a study of the civil rights movement, I used books, journals, and periodical; papers and oral histories in archives, museums, and libraries; videos and artifacts; interviews with both experts and participants in my story; and site visits.

My challenge was to blend together all this information to create a compelling story with a compelling point.

Whats the best way do do this? If you get into the habit of creating fragments, it will be easy. You’ll write about specific moments (scenes) and specific ideas (summaries). Different research materials will be useful for different fragments. Some of my favorite fragments for Nobody Turn Me Around came from videos; others from interviews; others from archives; others from a blend of sources.

Don’t decide to do a fragment based on a single piece of research material (like a great oral history or video). Instead, remember to figure out what One Idea you want to convey in the fragment. Use whatever speaks to that One Idea. It could be obe poece of evidence or it could be many.

7. Write fragments first–and organize them into distinct categories.

The biggest mistake most writers make–besides using traditional outlines–to to try to write whole chapters from the beginning to the end. It cannot work. Any sophisticated piece of writing is really a collection of smaller fragments. Therefore, write fragments.

A fragment is a short piece about one aspect of a subject. It could be as short as a few hundred words or as long as 10 or 20 pages. It depends on the complexity of the subject, the audience’s knowledge of key concepts, the density of the writing, and more.

I first discovered the fragment idea while reverse-engineering Truman Capote’s true-crime classic In Cold Blood. Capote does not use traditional chapters. Instead, he collects and arranges short fragments into four sections. Each fragment takes the story one step forward–never more.

8. Don’t obsess about its overall structure … but do play around with the possibilities.

Every piece of writing is a journey, which takes the reader from one place to another different place. So when you organize your fragments and chapters, think of that journey. Where do you want to “meet” the reader at the beginning? What does the reader know at the beginning? Then, where do you want to take the reader? What do you want them to know at the end that they didn’t know before?

Once you know the beginning and end, figuring out the steps gets easy. It’s like taking a trip. When I took a cross-country trip, I could figure out all the middle steps once I knew I would start in Charlottesville, Virginia, and end in San Diego, California. I could break the trip into eight-hour legs, each of about 400 to 500 miles. At each stop I plotted my way to the day’s destination. I even decided when I wanted to take a detour, like my visit to my college pal randy or a few hours at the Grand Canyon.

That’s how writing a big project works. Don’t outline the piece in the traditional way. Instead, break it into mini-journeys. Go to just one destination in each mini-journey. Collect a bunch of mini journeys on different topics. Then when you have enough — it could be anywhere from 20 to 40 of them — see what order works best.

Great writers like John McPhee and Robert Caro create 3×5 cards or sheets of paper that note their books’ many pieces. They tape or tack them on a wall, stand back, and look at the overall shape … then move them around. They spend countless hours, at the end of their process, moving these pieces until they fight the perfect flow from beginning to end, in all the fragments, sections, chapters, and whole work.

9. Edit like a pro.

In every great creative work, the finishing touches can spell the difference between good and great. If you’ve done an amazing job researching and writing, congratulations. You are nine-tenths of the way home. But that last one-tenth can determine who reads it, what kind of respect you earn, and how it might evolve into a book or articles.

I have described a simple and fail-safe editing process in The Elements of Writing, but allow me to sketch out some simple procedures and techniques.

First, go from big to small. You would not begin a kitchen renovation with the detail work on window ledges and plates for light switches; you’d begin with the basic structure–the walls and flooring, electricity and plumbing systems, cabinets and appliances, etc. After dealing with these big pieces, you’d move to smaller elements like furniture, woodwork, lighting, painting, and window and other details.

The same goes for big pieces of writing. Once you have gathered and organized your fragments into a whole work, start to examine all the elements. Start with the overall structure. Does your ONE Idea structure all the pieces? Do all the sections and chapters take us on a journey to that One Idea? Does each section and fragment explore one distinct piece of the whole? Does it start strong and finish strong? Then focus on smaller details? Do all these pieces move, like a pendulum, from scenes to summaries? Do all the paragraphs state and explain one idea? Then focus on the granular details: clunky phrases and repetition, words and phrases, spelling and grammar, and of course style and flow.

Start big, go small.

10. Give yourself a productive (not overwhelming) routine.

Writers give each other all kinds of advice on the writer’s life. Work in the morning. Work at night. Write at least two hours a day–no, four hours. Do research first, then write. No, write as you gather information. Stop in mid-thought. Set an agenda for the next day. Go where your information and imagination leads you.

Look, everyone’s different. You have to find your own routines. But I do have some ideas that everyone seems to accept.

First, write something every day. If you want to set a target, like 500 words a day, great. But write something. My experience is that you should almost always avoid big word targets. Why? Because you’ll usually fail. Better to say that you’ll write something every day than 500 words and miss your target. People tend to abandon goals when they fail to meet them. But you should be able to write something every single day. And here’s the magic: When you write something every day, you will often get into a groove where you accomplish more than you would have ever imagined. If you can stay in that groove, great–keep going. The next day, just say you’ll write something. You might only write 250 words, but that’s OK. Your work will set you up for bigger days later on.

Second, read something every day. When I was in grad school, my friend Nathalie had to finish her thesis in a year because she was moving back to Paris. But she refused to deny herself fun exploring the U.S. So every day she photocopied and read five journal articles. She set aside time, between classes, to knock off 10 or 20 or 30 pages at a time. These articles accumulated and before long she had lots of information to explore her topic.

What you need to read will vary according to your discipline and topic. But set a reachable daily goal–and meet that goal every day.

Third, schedule your other work. Whether you need to interview subjects, travel to archives, or conduct experiments in a lab, keep some kind of calendar. We tend to do what we put on a schedule. Again, don’t get too ambitious. But the more explicit you are, the more real these tasks become.

Fourth, avoid all distractions. This might be the most important tip of all. You cannot think if you get interrupted by texts, Netflix shows, noise in the apartment, friends who want to go get a beer, etc. You need total concentration. You will be at least twice as productive with total concentration than with fragmented work time. So when you work, just work. Focus on just one challenge at a time. Turn off your phone. Nobody needs you when you’re working. You’re not the president or CEO; you just a grad student.

Don’t just turn off your phone. Put it in another room. Studies show that a phone is distracting even if it’s off and face-down on the table. The phone’s mere presence is a siren song. Get rid of it. If you really love your phone and all its magical apps, think of it this way. If you remove it during your work time, you’ll have more time to immerse yourself in it later.

Do something to get into the flow. I often listen to New Age/acoustical music (my go-to site is Hearts of Space). Research shows that the rhythms and wavelengths of New Age music improves concentration. You get lost in time as you move deeper and deeper into your subject. When you need to puzzle out a problem, you can isolate the key ideas and think about their relationships. To me, the key to acoustic music is that I rarely tap my toes. If I listen to Springsteen or Rachmaninoff, I start paying attention to the music. My attention shifts from work to tunes. Somehow, this doesn’t happen with Libera or Andreas Vollenweider or Clannad or Enya.

By the Numbers: Distraction

The hardest thing to do these days is to concentrate. But that’s the single most important skill for writing. Here are some relevant numbers, from Deloitte Global Mobile Consumer Survey’s survey of 1,634 smartphone users in July 2017:

- 47: Number of times smartphone users in the U.S. check their phones each day.

- 85: Percentage of people who use the cellphone while talking to family and friends.

- 80: Percentage of people who check their phone within an hour of going to bed or getting up.

- 35: Percentage who do it within five minutes.

- 47: Percentage who have tried to limit their cell use in the past.

- 30: Percentage who have successfully limited their cell use.

During November–National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo–400,000 people dedicate themselves to writing 50,000 words toward a novel. Participants get together in bookstores, church basements, coffee shops, classrooms to feed off each others’ energy and write an average of 1,666 words a day. Of course, people also write alone, at kitchen tables, on sofas, in candle-lit garrets, and more.

During November–National Novel Writing Month, or NaNoWriMo–400,000 people dedicate themselves to writing 50,000 words toward a novel. Participants get together in bookstores, church basements, coffee shops, classrooms to feed off each others’ energy and write an average of 1,666 words a day. Of course, people also write alone, at kitchen tables, on sofas, in candle-lit garrets, and more.

By the time we have decided to write for an audience—to share thoughts, voluntarily, with anyone who will listen—we have developed a whole storehouse of experiences and memories, thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, and insights and ideas.

By the time we have decided to write for an audience—to share thoughts, voluntarily, with anyone who will listen—we have developed a whole storehouse of experiences and memories, thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, and insights and ideas.