The first piece of advice that all writers get is to “write what you know.”

By the time we have decided to write for an audience—to share thoughts, voluntarily, with anyone who will listen—we have developed a whole storehouse of experiences and memories, thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, and insights and ideas.

By the time we have decided to write for an audience—to share thoughts, voluntarily, with anyone who will listen—we have developed a whole storehouse of experiences and memories, thoughts and feelings, hopes and fears, and insights and ideas.

The trick is to use this storehouse to inspire and drive your writing—without creating unnecessary barriers.

National Novel Writing Month, a k a NaNoWriMo, offers an ideal opportunity to plumb your conscious and subconscious minds. Day by day, you can make deliberate efforts to understand yourself—and use that understanding to create something new.

But you don’t need to wait till November. Set yourself a goal to get a complete a draft of a novel–or memoir or how-to book or any other major piece of writing–in a month.

Without further ado, here’s your 30-day plan for connecting what’s deepest inside you to the novel you want to write—the novel you will write—this November.

1. “Writing is a code.” That’s what Margaret Atwood says, anyway. We all communicate all whole lives. But to become masters, we need to master specific skills and “tricks of the trade.”

Tasks: (1) Spend 15 minutes brainstorming the codes you’re going to have to crack as a writer. (2) Write 2,000 words describing what challenge your hero faces, how he’s going to crack the code

2. The journey. The ancient Greeks said: “Look to the end.” Every story takes the characters—and the reader—on a journey to some powerful ending. The novelist John Irving actually writes the last paragraph of his books first. He keeps that last paragraph as a North Star for his writing process. So ask yourself: Where do you want your characters to end up? How d you want them to differ b y the time they have experienced their adventure?

Tasks: (1) Imagine finishing your novel—how it all comes out. (2) Write your last paragraph and your last 2,000 words or the first and last paragraphs of many scenes of summaries.

3. The Arc. Aristotle said that great drama resembles an arc, which begins by introducing the characters and their world, then confronts the hero and others with increasingly intense challenges, and finally resolves with a new understanding and significant change in the character’s lives.

Tasks: (1) Sketch out an arc for your life—first, as if your life were to end today; second, as if you would live till 90. (2) Write full action passages for one or two of the following points along the arc: Opening scene … The challenge … Crisis 1 … Crisis 2 … Crisis 3 … Recognition … Reversal … Denouement.

4. Scenes and summaries. All stories move back and forth between scenes and summaries. Scenes engage the reader physically; summaries allow a moment of respite and an opportunity to explain ideas and background. Scenes show particular people doing particular things at particular times and places, with particular motions and emotions. Scenes zoom in to capture the details of people’s lives, with a moment-by-moment description of action. Summaries offer sweeping assessments of the bigger picture, with an emphasis on what it all means, in order to set up scenes.

Tasks: (1) write does tabloid headlines for as many scenes and summaries as possible. (2) Write one scene and one summary, each 1000 words long. With the scene, just show the characters doing one thing after another—no exposition!

5. The hero. Who’s your hero? What’s his dilemma? All great stories offer the reader a character to root for—often superior in many ways, but still human with a need to deal with flaws and difficult situations. Is the hero young or old, virtuous or troubled, sociable or hermetic, tall or short, dark or light, fit or flaccid, rich or poor, happy or dissatisfied, knowing or clueless, young or old, male or female?

Tasks: (1) Brainstorm the various challenges you’ll face as an author. Make a list. Tack it over your computer. (2) Write one scene and one summary describing the hero’s deepest challenge.

6. World of the Story. The setting not only offers a “container” for a story, but also reveals much about the characters and their community. The setting is rich with clues about the characters, their struggles, their ideals, and their capacity to act.

Tasks: Describe your situation, your setting, a “day in the life,” and how it affects your work. (2) Describe one or two settings, in a total of 2000 words, by showing the characters moving around. Have each one of these as the openings of a chapter or scene. Example: Herb Clutter’s promenade.

7. The Crisis or Call. Every hero needs to face a crisis or call to action. In the midst of living a settled life, something happens to challenge the hero. Something internal (unresolved feelings and relationships, goals and ambitions, memories from the past) or external (an economic, romantic, social, professional, or other upheaval) takes the hero out of her comfort zone. Or some event issues a challenge. At first, she refuses to answer the challenge. But over time, she realizes she has no choice to do so.

Tasks: (1) Write down three times when you have faced a new, unexpected challenge in your life—and how you responded. Note how you felt physically amidst these challenges. (2) Describe the moment when your hero was first introduced to the challenge that he must face—and how he responded. Include denial and selfmisunderstanding. 2000 words.

8. The hero’s dossier. To tell a satisfying story, you need to know your hero—and other characters—inside and out. Who are these people? What do they look like? Where do they come from? What do they want? What have they done? Who do they spend time with? What do their mannerisms and habits betray about them?

Tasks: (1) Brainstorm intensely on your life and values. (2) Fill out a “character dossier” and write one scene and one summary to show that character to the reader. 2000 words, 1000 words for each fragment. 5. 6. 7. 8.

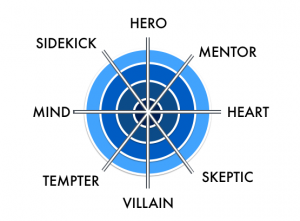

9. The wheel of character types, Part 1. The best stories use action to reveal something about the hero and other characters—especially what those characters repress. Every character has an opposite. These opposites resist each other, but they’re also drawn to each other. What’s different in the opposite character is something that exists in all of us, but repressed. Start by considering the most consequential of character types—the hero and villain.

Tasks: (1) Think of your biggest rival at one or two specific moments in your life. (2) Show the first interaction with the hero and villain (1000 words). Show a later interaction that reveals something totally surprising—but not, in retrospect since the hero and villain contains parts of each other.

10. The wheel of character types, Part 2. Other characters help to draw push the story forward. The pairs of opposites include the mentor and tempter … the sidekick and skeptic … and the mind and heart. Each one of these three pairs of types represents something in all of us.

Tasks: (1) Brainstorm for 15 minutes, feverishly, about two character types in your life. (2) Create scenes two characters—besides the hero and villain—acting or speaking with reference to the hero. Could be mentor, tempter, sidekick, skeptic, heart, or mind.

11. The wheel of character types, Part 3. Things get really interesting when three characters are part of a scene. Whenever two characters develop a relationship—of alliance or opposition—a third party lurks to scramble that relationship. Two lovers, for example, encounter a past lover. Two business partners encounter a revolt among workers. Parents encounter the demanding desires of a child. And so on.

Tasks: (1) Brainstorm about the dynamics of the triangles in your life—what make them stable, what made them volatile and changing. (2) Create scenes with interactions of TWO triangles. By now, make sure you cover all of the character types in the last three days. 9. 10. 11.

12. Act by Act. Give your story three distinct acts, using the narrative arc: The World of the Story, rising action, and resolution. In the World of the Story, show the people and places in a state of calm and order. Think of this as a settled status quo. Then show the hero confronted with something difficult—something so difficult, in fact, that hero cannot bear to face it head-on. Show that hero slowly, painfully, dealing with different aspects of that challenge, one by one. Show the character change with these encounters. Finally, give the hero an “aha”: moment, when he begins to understand the true nature of his life and world—and the need to change for his own survival and wellbeing.

Tasks: (1) Think about your life as a three-act play. How satisfying is the “conclusion”? Sketch your story on a sheet of paper. Ask what you need to reach your own “resolution.” (2) Review your story to date. Write opening and closing paragraphs for each part, making sure that you start and end strongly. Write a total of 200 new words, however distributed.

13. Dialogue. People’s language—their choice of words, their use of slang, how quickly they speak, their conversational tics— reveal much about their character. How they interact with others—whether they listen, interrupt, stay on the subject, show respect—reveals even more. And of course people speak differently in different places with different people.

Tasks: (1) List three important conversations you’ve had in your life. Show how you connected—or failed to connect—with the other persons. Try to understand what made the conversation work or fail. (2) Write three scenes, 750 words apiece, with only dialogue.

14. Parallel arcs. The best stories are really two or three stories rolled into one. Besides the main plot, which involves the hero’s journey, there are two or three subplots involving other characters or ideas. These plots and subplots intersect at critical moments in the story.

Tasks: (1) Write down the essence of the “plotline” of your life. Then write down the various subplots, involving friends and family and others, that intersect with your story at critical times for both. (2) Sketch out two subplots of your story. For each, describe the main character, the journey, barriers along the way, moments of intersection with the main plot, and how the journey ends.

15. Denial. Most stories are about one thing: How the hero and other characters deny some essential reality, and then struggle because of the denial. When the hero is first presented with his challenge, he does everything in his power to avoid confronting the truth. And for good reason: Change is painful, emotionally overwhelming. But a series of events force the hero to deal with pieces of the challenge.

Tasks: (1) Honestly, with no self-editing, make a list of the problems in your life that you avoid and try to deny. (2) Write a scene in which another character confronts the hero about a problem that he has been denying. Then write the background summary that shows the origin of this denial, with reference to past events—and try to build scenes into that summary as much as possible.

16. The Time Element. “Nothing concentrates the mind like a pending execution,” Samuel Johnson once said. Time pressures force characters to think, act, respond energetically—making more mistakes, but also discovering more things. Suspense begins with a ticking clock. TV shows like “Mission: Impossible” and “24” explicitly race against time. Even stories that suspend time, like Ivan Goncharov’s Oblomov, create tension about the question: Will the hero reenter the real world in time for a decent life? =

Tasks: (1) summarize all the tasks still ahead to finish your novel draft. (2) Write TWO scenes, 1000 or so words apiece, describing the hero or other character racing against the clock.

17. Taking Risks. The “Hail Mary” is one of the most exciting plays in football. With the game at stake, the quarterback launches a long pass with the hope of scoring big. But it’s also a risk—the other team could intercept the ball. Life is like that too. Sometimes we have to risk losing a lot to gain a lot.

Tasks: (1) Make a list of the riskiest things you have done, either on purpose or by neglect or recklessness. (2) Write a scene in which the character takes a big risk, then write a scene where his villain takes a big risk.

18. Beats. Every scene is a series of actions, one after another. Characters constantly thrust and parry, sometimes dramatically and sometimes subtly. To give your scene pacing and meaning, you need to make sure that every moment advances the story.

Tasks: (1) For ten minutes, write down everything that you said with a friend in a recent conversation. Show a constant move back and forth from positive to negative values and back again. (2) Write two scenes of about 1000 words apiece. Make sure that every moment produces some reaction and/or advances the story. Take out all details and actions that do not move the scene toward a memorable conclusion.

19. Suspense. Engage the reader best by creating a sense of uncertainty, which gets the reader guessing, and then solve that uncertainty. Cliffhangers bring the story to a point when something important is about to happen—and then break off the action.

Tasks: (1) For ten minutes, write down the moments in your life when you know something big was about to happen—but you didn’t know what. (2) Write two 1000-word scenes that do just this. Move the scene forward, beat by beat, and then end with an almost-dramatic conclusion. Save that conclusion—the answer to an important dilemma for the character—for the next section.

20. Senses. People— even reader—are physical creatures. So you need to make your story crackle with physical details. Make sure you use specific, precise words to evoke sights, sounds, and feelings.

Tasks: (1) write down as many sensory words as possible. Make as many observations as possible about the sights, sounds, and tactile qualities of people and things in your vicinity. (2) Go over all your fragments so far and replace all general descriptions with something visual, auditory, or kinesthetic.

21. Sentences. If you can write a good sentence, you can write anything. All too often, we get lost in long and meandering sentences. It’s only natural when you are engaged in such a creative process: one idea prompts another idea, then another and another.

Tasks: (1) Write down, one sentence at a time, all of the writing tasks you need to finish to complete your novel this month. Use full sentences. (2) Go through your drafts so far, sentence by sentence, and make sure that each one takes the characters—and the reader—from one place to another, different place.

22. Shapes. Writing uses three basic shapes—a straight line, a circle, and a triangle.

Tasks: (1) Sketch out your life, so far, using a line, circle, and triangle. (2) Write three separate passages of about 750 words apiece, either scenes or summaries. In one passage, take a straight, linear path. Don’t double back, don’t skip off to provide background; just show one thing after another. In the second passage, show a character or idea begin one place, develop, and end up where you started. In the third, depict the interaction of three characters and/or three ideas. Show how, when two interact with each other, the third has the potential to change their interactions.

23. Numbers. All good ideas can be expressed as ones, twos, threes, or longer lists of things. Ones put a person or place, hope or fear, thought or idea, front and center. You look at that one thing from different angles, as if inspecting a diamond. Twos present complements and oppositions—sidekicks and enemies, reinforcing or opposing ideas, consonant or conflicting feelings. Threes present the opportunity for real complexity. Think of the lover’s triangle. Whenever two sides bond, the third party lurks nearby, ready to upset everything.

Tasks: (1) Write down the most important idea in your life, something about your relationship with one important person in your life, then the most dynamic triangle in your life, and finally the five most important people, events, or values in your life. (2) Write four fragments of 500 to 750 words. In one fragment, focus on one person, thing, or idea. Make everything else revolve around that one person, thing, or idea. In another fragment, show two people, things or ideas competing with each other— and, below the surface, reinforcing each other. In the third passage, show a triangle of people, things, or ideas. Show how any two corners of the triangle can get stabilized or destabilized by the third. Finally, create a passage that explains or shows the complexity of things by listing a whole bunch of things—people, events, things, tasks, debts, fears, etc.

24. Discovery/exploration of sketchy places. Steven King says he writes scenes by imagining places and events that would scare him. Scary places are all around us—roads and highways where we can crash or get hit by a car … pools where children can fall and drown … parking garages or alleys where we can be mugged … hospitals where we can be mistreated or even tortured … taxis where drivers can take us to dangerous places … even offices where nightmare bosses and colleagues torture us emotionally.

Tasks: (1) Describe the freakiest place you’ve ever been in your life, with as many precise details as possible. (2) Create one sketchy place—a place that’s weird, gross, dangerous, sickly, otherworldly, creepy, Disneyesque, or otherwise alienating—and make something consequential happen to your character there.

25. Love. What captures the heart—the emotions, longing, deep and abiding interest or even obsession—of the hero or other characters? How the hero encounters and responds to love defines that character like nothing else.

Tasks: (1) Make a list of the loves of your life, with specific details about what was good and what was bad— and what were most moments in these relationships was most revealing about your character. (2) Write two scenes. In the first scene, show the moment when the hero meets his or her love interest for the first time. Show the character surprised by his or her interest—and holding back for some reason. In the second scene, show a major conflict between the two lovers. Don’t explain the conflict—show the conflict, so the reader can make sense of it on her own.

26. Failure and Frustration. Nothing matters more to a story than failure and frustration. How a character fails—coming up short in an honest effort or neglecting or denying something important—reveals something about his self-mastery. And how he responds—whether he learns and grows or rigidly rejects opportunities for growth—reveals his character.

Tasks: (1) Write down three moments of failure in your life— with as many details as possible about how you responded. (2) Write two short scenes—anywhere from 250 to 500 words—describing the moments when a character experiences failure. Try to show how their expressions and body language change at the moment when they realize they have failed.

27. Not What It Seems. The best stories operate on at least two levels—the level of the obvious and the level of the meaningful. Characters carry out different tasks, interact with others, make mistakes and grow—but underneath, they are really struggling with deeper challenges.

Tasks: (1) Think of three times in your life when you worked or played hard to achieve something (e.g., success in school, sports, work, love)—when something larger was really at stake (e.g., pride, dignity, revenge, honor, vindication). (2) Create two scenes of 1,000 words apiece in which your character strives for one thing, obvious for all to see—but gets his or her motivation from a deeper psychological yearning.

28. Powers. What are the hero’s greatest powers— and how does he deploy them? Does the hero possess extraordinary physical might? Intellectual powers? Emotional insight? Social wherewithal? Or does he possess some supernatural connections to other beings?

Tasks: (1) Make a list of people you know with the greatest physical power, intellectual power, social power, financial power, and moral power. (2) Write two scenes, each 1000 words, describing clashes of characters with different powers. Show how these characters attempt to use these powers, and how they respond to each other. For example, show someone of great wealth interacting with someone with social charisma or someone with a strong moral compass.

29. Surprises. What surprises can you sprinkle throughout the story? Above all, good stories show us things we cannot imagine without some prodding. If everything is predictable, after all, why bother reading? Storytelling is a two-way process. The writer offers a series of moments, with just enough details for the reader to add her own memory and imagination. Think of storytelling as a relay race, where the writer offers something surprising, then the reader adds her own thoughts.

Tasks: (1) List the ten most surprising things to happen in your life. Looking back, identify the missed signals that would have made these events less surprising. (2) Create two scenes in which important surprises happen to the hero and one other character, either together or separately. Then write scenes or summaries that provide the backstories, setting up those surprises.

30. Recognition and Reversal. Great stories end with a new level of understanding—for the story’s leading character’s and for the readers.

Tasks: (1) Make a list of three times in your life when you came to a brand new understanding of yourself, your values, and how the world works. Write down what caused you to gain this new wisdom. (2) Write the climactic scene of your novel. Show the character saying and doing something that he would not have been able to say or do before. Show how this new wisdom changes everyone around him.

Before you go . . .

• Like this content? For more posts on writing, visit the Elements of Writing Blog. Check out the posts on Storytelling, Writing Mechanics, Analysis, and Writers on Writing.

• For a monthly newsletter, chock full of hacks, interviews, and writing opportunities, sign up here.

• To transform writing in your organization, with in-person or online seminars, email us here for a free consultation.