I wrote this brief tribute after Bill Nack died in 2018.

When I think of Bill Nack, I want to call him one of the great sportswriters of our time. But he was really one of the great writers, in any field, of our time.

The reason is threefold. First of all, he was a hell of a reporter–dogged, tireless, determined to keep working till he got all the details right. Second, he was a great stylist. He did things with words that I never saw anyone else do. He built every sentence on a strong foundation. On that foundation he worked magic, with revealing ideas and images and telling phrases made possible by his first-rate intellect and great reporting.

The reason is threefold. First of all, he was a hell of a reporter–dogged, tireless, determined to keep working till he got all the details right. Second, he was a great stylist. He did things with words that I never saw anyone else do. He built every sentence on a strong foundation. On that foundation he worked magic, with revealing ideas and images and telling phrases made possible by his first-rate intellect and great reporting.

Third, he had a great heart. He cared about everything he did. In one of my favorite pieces, Bill was assigned to find the mad genius Bobby Fischer, the chess master who degenerated into a ranter of anti-Semitism and ugly conspiracy theories. Ahab sought his whale with gusto. He worked his networks and tracked rumors and sightings. At one point, Bill found himself at the Los Angeles Public Library, which Fischer was rumored to haunt. Then … there he was! Bobby Fischer! But when Bill found his whale, he let him go. Whatever Fischer’s news value and however crazy his behavior, Bill decided, he should be left alone. The search, it turns out, was the story. Bill not only knew how to go; he also knew how to stop.

Secretariat: Bill’s Greatest Subject

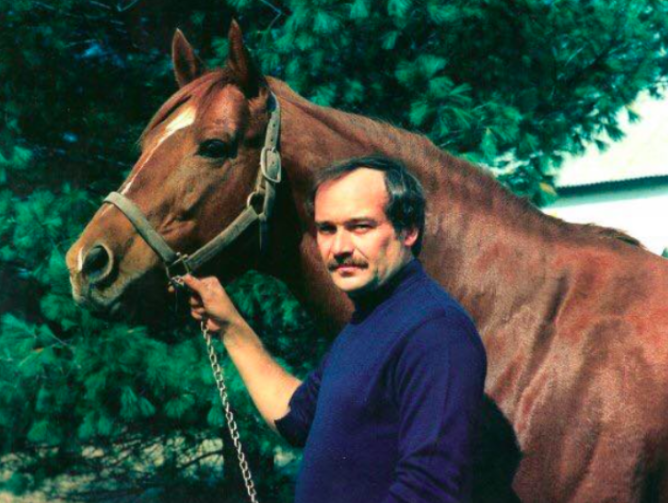

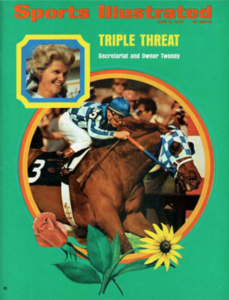

Everything Bill did, he did with heart. He was most famous for his masterful book about the racehorse Secretariat. During that magical summer of 1973, when Secretariat electrified the Watergate-weary nation in his romp to the Triple Crown, Bill knew the horse better than anyone. In the weeks before the Belmont Stakes, he lived in the stables with the horse. He knew everyone in racing because he loved his subject and he wanted to share it with others.

I met Bill in 1978 when he was a columnist for Newsday and lived in Huntington, N.Y., my hometown. He called me after I won a scholarship to Vanderbilt (for which he had been a judge the year before) and we went to lunch at a Greek joint on New York Avenue and then to his house near Huntington Bay. We talked about books and writing. He gave me a collection of essays by Dwight McDonald. His daughter danced in and out of the room. Over the years we connected once in a while.

Years later, when I was teaching writing at Yale, I decided to use Bill’s brilliant piece “Pure Heart,” about the death of Secretariat. I wrote to him to learn how he came to write the story the way he did.

‘Pure Heart’: Brief Excerpts

To set the stage, Bill’s story begins like this:

Just before noon the horse was led haltingly into a van next to the stallion barn, and there a concentrated barbiturate was injected into his jugular. Forty-five seconds later there was a crash as the stallion collapsed. His body was trucked immediately to Lexington, Ky., where Dr. Thomas Swerczek, a professor of veterinary science at the University of Kentucky, performed the necropsy. All of the horse’s vital organs were normal in size except for the heart.

“We were all shocked,” Swerczek said. “I’ve seen and done thousands of autopsies on horses, and nothing I’d ever seen compared to it. The heart of the average horse weighs about nine pounds. This was almost twice the average size, and a third larger than any equine heart I’d ever seen. And it wasn’t pathologically enlarged. All the chambers and the valves were normal. It was just larger. I think it told us why he was able to do what he did.”

Soon we understand that “the horse” is Secretariat and we get a glimpse into Bill’s passion. He writes:

Oh, I knew all the stories, knew them well, had crushed and rolled them in my hand until their quaint musk lay in the saddle of my palm. Knew them as I knew the stories of my children. Knew them as I knew the stories of my own life. Told them at dinner parties, swapped them with horseplayers as if they were trading cards, argued over them with old men and blind fools who had seen the show but missed the message. Dreamed them and turned them over like pillows in my rubbery sleep. Woke up with them, brushed my aging teeth with them, grinned at them in the mirror. Horses have a way of getting inside you, and so it was that Secretariat became like a fifth child in our house, the older boy who was off at school and never around but who was as loved and true a part of the family as Muffin, our shaggy, epileptic dog.

On a trip to Kentucky, Bill learns that Secretariat has a terminal illness. Over the years, he has visited Secretariat on a regular basis. He decides to visit the horse and his keepers, one last time. The story ends when Bill hears the news, on the phone in his hotel room, that Secretariat has died.

The last time I remember really crying was on St. Valentine’s Day 1982, when my wife called to tell me that my father had died. At the moment she called, I was sitting in a purple room in Caesars Palace, in Las Vegas, waiting for an interview with the heavyweight champion, Larry Holmes. Now here I was in a different hotel room in a different town, suddenly feeling like a very old and tired man of 48, leaning with my back against a wall and sobbing for a long time with my face in my hands.

I love “Pure Heart” because it is the perfect alchemy of mind, heart, and soul. It’s a personal story, told with emotion, but there’s not a manipulative word in the whole piece. There’s something deeply true in the story.

How Did Bill Write ‘Pure Heart’?

When I wrote to Bill asking for the story behind “Pure Heart,” I did not expect such a robust response. But Bill was a generous man with a love of writing. He liked to talk shop. Here’s what he said:

I didn’t even want to write “Pure Heart” after Secretariat’s death. I had been writing about him for so many years, in so many forms, that I felt I’d written enough. But my best friend, Time sports editor Tom Callahan, urged me on several occasions over the winter of 1989-90–the months after the horse died–to do a final piece for Sports Illustrated as a way of bringing the whole saga full circle.

I resisted, not wanting to revisit the feelings of loss, all the emotions it would engender, until I finally faced the idea that I had to write it, that I owed it to the story to finish it.

That early spring I broached the idea of a final, first-person memoir with SI‘s managing editor, Mark Mulvoy. He immediately told me to get started. I wrote it in one 24-hour day of Derby Week in Louisville, at the Galt House, beginning it at 9 a.m. on Wednesday morning and finishing it at 9 a.m. on Thursday morning.

The Story of the Ending

I had told a couple of the editors about the autopsy report revealing the massive heart, and they loved it. When I wrote the end of the story as it finally appeared, about me finding out the horse had died and my reaction to the news, I then spent three more exhausting hours trying to figure out a way to flash forward to the autopsy, but none of my ideas worked. The ending with me standing in that room sobbing with my back against the wall was the natural end of the story, but I was determined to get that anecdote in.

Around noon, the magazine’s executive editor, Peter Carry, called and said, “Bill, What are you doing? I heard you are trying to write a new ending to include that autopsy report.” I said I was. “Don’t. Stop. Leave the ending alone. We’re considering using the autopsy at the beginning of the story, as a precede.”

The Story of the Beginning

An hour later, editor David Bauer called and asked me to write a 200-word precede about the horse’s death and the autopsy that followed. “Where are you going to put it?” I asked. “At the beginning. As a precede that will run in large type before the actual story.”

“This is going to ruin the lead,” I said. “It’ll be like we had two leads and couldn’t decide which one to use, so we ran both of them.”

“No, it won’t,” David said. “It’ll be fine. You’ll see. And don’t mention the horse’s name. Just call him ‘The horse.’ The reader will figure it out. We want to use the autopsy story but it does not fit at the end. You couldn’t have written a better ending and any kind of postscript would ruin it. So just give me 200 words about the horse being put down and then the autopsy. Very simple and straightforward.”

And so, somewhat skeptically, I wrote those 200 or so words. That precede was a brilliant idea, I must confess, and the autopsy story became one of the most oft-told tales in the lore of thoroughbred racing. Secretariat became the horse who had the giant heart, the biggest motor, the engine that never stopped beating. And it was all true.

It was a perfect story about a perfect tribute to a perfect horse. Read “Pure Heart” and read Bill’s backstory and you get an idea of what real writers do.

Bill closed his note with an invitation I wish I had found a way to accept.

“We must have lunch someday … at a Greek restaurant. Ever in D.C.?”