How can we see–really see, and not just project–what’s in front of us?

That’s the writer’s ultimate job. The best writer is an observer. The best writer sees what others do not see. This writer pays attention, carefully and with an open mind, to what’s going on. Rather than falling into lazy habits and assumptions, the best writer looks to see what is not instantly apparent.

That’s the writer’s ultimate job. The best writer is an observer. The best writer sees what others do not see. This writer pays attention, carefully and with an open mind, to what’s going on. Rather than falling into lazy habits and assumptions, the best writer looks to see what is not instantly apparent.

Which reminds me of a morning encounter on Election Day 2016.

The Encounter: A Story

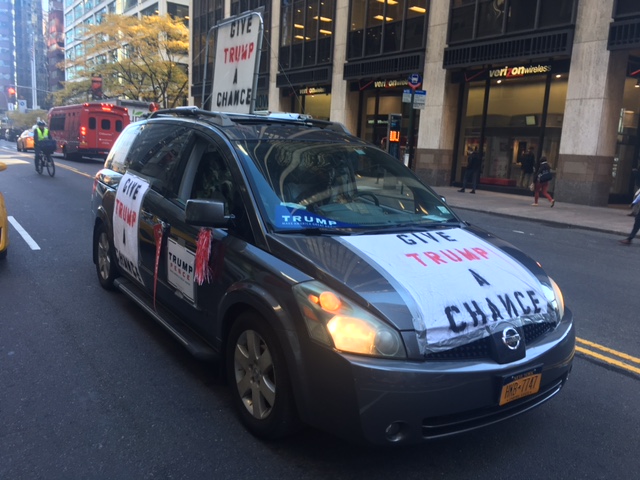

I was walking down Wall Street. As I crossed Water Street, I saw a car stopped at a red light.

I was intrigued enough to stand in the intersection to take a picture. I saw a Honda covered in pro-Donald Trump signs. The signs weren’t printed professionally. It looked like an amateur job.

Then I wondered about who would drive such a car. I imagined a “typical” Trump voter — a blue-collar worker, white, probably stocky, maybe tattooed. There’s no way to read someone’s heart from a distance, but I imagined someone thrilling to Donald Trump’s nativist rhetoric, his disdain for immigrants and minorities. I thought of Trump’s depiction of cities as dens of crime and disorder. I thought of Trump’s claims about illegal immigrants and how a wall along the Mexican border would keep them out — even the people who overstayed a visa or came to the U.S. from places beyond the Americas.

So who was this Trump supporter? Maybe he was a veteran, but more likely he was a middle-aged guy from … who knows? Queens? Jersey? Out of town?

Automatically, I imagined a picture of something that I did not see.

Then I crossed the street. I took a few steps before deciding to go back to see who this Trump supporter was. I clicked another picture before the light changed.

I was surprised. I was not expecting to see a black man behind the wheel. This was not the prototypical Trump supporter. Sure, I knew that Trump got some black support. Nationwide, we would soon know, Trump won 8 percent of the black vote. He also got 29 percent of the Hispanic vote. Both totals, for what it’s worth, were better than Mitt Romney’s numbers in 2012. Romney got 6 percent of the black vote and 27 percent of the Hispanic vote.

My guess about the Trump support was not unreasonable. Statistically, it was correct.

The Built-In Imperative to Predict

The brain, says the business consultant David Rock, is a “prediction machine.” Before we’re even aware of what we’re doing, we guess what’s going on.

“Your brain receives patterns from the outside world, stores them as memories, and makes predictions by combining what it has seen before and what is happening now,” Rock writes. “Prediction is not just one of the things your brain does. It is the primary function of the neocortex, and the foundation of intelligence.”

When you experience something, your mind begins to search through your memories. Rather than paying close attention to the scene in front of you, your brain looks for something familiar. If there’s a “match,” the brain makes a prediction. If X happened before, something like X will probably happen again.

Biologically, we have a craving for certainty. That makes sense when you think of man’s evolution. For most of human history, people’s lives were “nasty, brutish, and short,” to use Thomas Hobbes’s famous phrase. People faced danger daily–from predatory animals, starvation, attacks by rival tribes, and disease. When we achieve a measure of certainty, we feel a rush of dopamine.

Robert Burton, a neurologist at Mount Zion Hospital in San Francisco, explains: “At bottom, we are pattern recognizers who seek escape from ambiguity and indecision. If a major brain function is to maintain mental homeostasis, it is understandable how stances of certainty can counteract anxiety and apprehension. Even though I know better, I find myself somewhat reassured (albeit temporarily) by absolute comments such as, “the stock market always recovers,” even when I realize that this may be only wishful thinking.”

The Writer’s Need to Resist

But here’s the thing: As writers, we have to work hard to avoid making conclusions before discovering the facts. A statistical is not a story. A probability does not provide the complex, nuanced information we need to understand the world.

In law, it’s a truism that eyewitnesses are notoriously bad witnesses. Eyewitnesses don’t see. Like the rest of us, they view something–often without paying close attention to the details that matter–and then construct a picture based on their existing knowledge and biases. That’s why circumstantial evidence (like fingerprints, items left at the scene of a crime, phone records, and the like) is usually more valuable in legal cases than eyewitness accounts.

The only way to discover something new — whether you’re witnessing an event, sifting documents, asking questions, or interpreting data — is to avoid predicting what you’re seeing.

The Beginner’s Mind

It takes work to avoid jumping to conclusions. The Buddhists have a term for this. It’s called the “beginner’s mind.”

“In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities, but in the expert’s there are few,” says Shunryu Suzuki in his classic work Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind. The more we know something, the less conscious and thinking we are about it. We take it for granted. We lose the sense of mystery and puzzlement when we know something as an expert. Too often, we cannot see something in front of us.

About the beginner’s mind, Abraham Maslow writes this: “They are variously described as being naked in the situation, guileless … without ‘shoulds’ or ‘oughts,’ without fashions, fads, dogmas, habits, or other pictures-in-the-head of what is proper, normal, ‘right,’ as being ready to receive whatever happens to be the case without surprise, shock, indignation, or denial.”

In conceding the election to Trump, Hillary Clinton said: “We owe him an open mind and the chance to lead.” An open mind does not mean acquiescence or a compromise of values. It does not mean forgiving the ugly or dishonest things he said in the campaign. It means only paying attention, carefully, to what you see. Only then can you really know what’s going on and respond appropriately.

Ten Steps to Cultivating the Beginner’s Mind

(1) Scanning: whenever you encounter something–new or old–make a point of scanning for surprises

Start by looking where you usually look. When you enter a park or a building or a mall, you have a tendency to lean in a particular direction, especially if you’ve been there before. As you look, stop. Pause for a few moments. And then look, deliberately, in different directions. If you veer to your right, toward the Starbucks, stop and start scanning to the left. Look up. Look into the distance. Look into a corner. Zoom in and look at the details.

(2) Note your predictions, then un-do them. Every time you assume something is going to happen–every time you make a prediction–stop and take note.

Just pausing will dramatically improve your beginner’s mind. Researchers say we have from 50,000 to 70,000 thoughts a day. They come in a rush, unbidden. They come along, like tourists bustling through Times Square, in bunches. Often they veer off into new bunches of thoughts.

Just hitting the “Pause” button will improve your awareness of this constant sc=tream of thoughts and predictions.

Now take it a step further. Label your thoughts and predictions. Like: “Oh, I just assumed…” Or: “Without pausing, I just thought that…”

Once you label your predictions, they fall apart on their own. You come into a park and see kids racing around. If you’re a grumpy old man, you might assume–you might predict–that they’re aimless youth, irresponsible, reckless, etc. When you stop and label that assumption, it falls apart. You start to notice more about them. Rather than projecting your own assumptions, you’re now paying attention.

(3) Be patient. We have a tendency–all day, every day–to jump to conclusions. Research shows that people’s first impressions, in a job interview or a social setting, make a greater impact than anything else. When we see, hear, or read something, we make snap judgments.

To control this tendency, we need to consciously slow things down. We need to say to ourselves: “OK, what just happened? What was that sequence of events that just happened?”

Let your ideas unfold, deliberately. If you find a salesman’s gambit persuasive, break down the experience into pieces. How did he greet you? What did he say? How did he appeal to your ego? To your insecurity? What kinds of promises did he make? How well did he answer questions? When did you get carried away, daydreaming about the wonders of that new purchase?

(4) Be childlike … and play dumb. It’s a cliche that children are full of wonder, with a desire to explore the world around them. They ask questions constantly. Unlike adults, they are not afraid of not knowing. “Why?” is the constant refrain of the curious child. All too often, parents mask their ignorance of a subject, when it would be far better to say, “I don’t know. Let’s find out.”

We’ll never get that childlike wonder back. But we can try. We can pretend we don’t know as much as we do. That actually shouldn’t be too hard, as long as we remember to try. Most of our knowledge, after all, is superficial.

When you encounter a scene, turn everything you think you know into a question. Rather than assuming, open up the possibilities. If you’re sure that the checkout clerk was dumb or the driver who cut you off was aggressive, open yourself to doubt. If you assume that the student was lazy or the athlete a great guy, open yourself to doubt.

(5) Avoid judgment: Avoid the words “should” and “ought.” Catch your assumptions and judgments–about everything–and deliberately un-do those assumptions and judgments.

When someone asks you something, start with, “I’m not sure.” When someone asserts an opinion with which you want to agree or disagree, pause for a moment. Ask yourself how you might conclude the opposite.

Notice when you label things as smart or dumb, creative or dull, cheap or expensive, beautiful or ugly, etc. Then, un-label them. Become agnostic on the question. Imagine not knowing or thinking or even caring, at least for the moment.

Every time you catch yourself thinking that something’s right or wrong, normal or abnormal, beautiful or ugly, smart or dumb–in fact, any time you find yourself thinking in dualities–stop!

(6) Be like Picasso. I’m talking about the late Picasso, who embraced a more abstract vision of the world.

Pay close attention to the shapes, colors, lights, textures, and sounds of things–not their meaning. Look for the circles and curves. Then look for squares and rectangles, and then the triangles. Observe how the pieces fit together. Notice the colors and how the colors define the shapes and play off each other.

Then listen. First, notice what you usually notice. Then pause and cock your ear for distant sounds. Listen to those sounds intently. Then listen to how the sounds collide against each other. If you’re in a cafe, listen to the sounds of the baristas and the customers making orders, then the sounds of people conversing at tables and the clack-clack-clack of laptops. Tune into whatever music is playing.

Do the same thing on the street and at a ballgame, in a college quad or cafeteria, in an office lobby or conference room.

Do. Not. Try. To. Make. Sense. Of. It. Just. Listen. And. Notice.

(7) Beware of bewitching stories. The human race is a storytelling race. We make sense of the world by making everything a story. When we encounter a great storyteller, we listen with rapt attention. Stories entertain and instruct. They give meaning to the world. That’s all good.

But stories, inevitably, leave lots out. Storytellers want you to pay attention to some things, but not others. They’re like magicians: “Behold as I distract your attention with this flashy trick, while I slip my hand into your pocket and take your wallet.”

Don’t trust stories. They are told to deceive as much as to inform. The simpler the story, the more you need to question it. Distrust, especially, the stories that depict whole groups as having the same qualities. Bigots assume that people from certain groups–race, religion, class, age, profession, education, etc.–behave certain ways. Maybe they do, usually, as I note in my Election Day story. But just because most people behave a certain way, don’t assume that everyone in the group does so.

Observe people, one by one, to see what they actually do. Look for ways that they contradict your assumptions.

(8) Let things unfold. A good writer acts like a tour guide. The tour guide does not point out everything on the tour. By focusing on a few telling details, she helps us to ignore irrelevant details.

Too often, writers attempt to explain every aspect of an issue at once. We pack lots of background information into a paragraph or two, tight as a tin of sardines. But too much information, too soon, overwhelms readers.

The more complicated your topic, the simpler you need to explain. Express one simple idea at a time, so that the reader follows every step of the process. Unpack the many complex aspects of an issue and explain them, one by one. Use simple, familiar terms.

Recipes offer another useful model for explaining. Cooks must perform their tasks one at a time, in the right order. To make a dish, you must move deliberately, step by step. Preheat the oven to 450 degrees. Then gather the eggs, flour, vanilla extract, sugar, chocolate chips, and so on. Then sift the flour. Then beat the eggs. Then mix the ingredients. Then grease the sheet. Then …

I once convened a writing class in a kitchen, where we made a pie. Each student participated. As students sifted and whipped and rolled, they spoke into a recorder. The student who organized the event narrated the process, offering comments the way about ingredients and her grandmother’s baking tips. Other students talked about family cooking traditions, special kitchen tricks, and likes and dislikes. Afterward, I transcribed the conversation. The result was a good first draft of an essay on cooking. From that point, the students knew how to explain anything well.

Writing requires the same process as cooking: take your time, do one thing at a time, in the right order, and explain as you go.

Here’s a good way to master this skill. Get a video of anything that interests you. It could be a great sports game, like the Super Bown or NBA Finals or an Olympic event. It could be a movie or live coverage of a news event. It could be a documentary by Frederick Wiseman. Play a scene a few times. Then go back and play it in slow motion. Write down every micro-event in the scene. You’ll be amazed at how much happens in just a few seconds. You can train yourself to notice.

(9) Reject causality–or look at things backward–at least for the time being. To understand anything, we need to get a sense for what causes what. We need to identify the “variables” that contribute to an outcome. But even when we gather lots of evidence for a proposition–like the idea that higher levels of education create economic opportunity–we have to be careful.

On its face, it makes sense. College graduates earn an average of $1 million more than non-college grads, according to research at Georgetown University. Annually, college grads earn $17,500 more than non-grads, according to Pew Research Center. The more skills you have, the more you can offer employers–and the higher wages you can earn.

But as Nassim Nicholas Taleb notes, the causal arrows often point in the opposite direction. The more money you earn, the more you use it to get an education. You don’t make the money because of the education; you get the education because of the money.

In fact, Taleb argues, education is often a barrier to economic achievement. “It’s good to have a class of people who are educated,” he says. “But education is the enemy of entrepreneurship.” Scrappy, dedicated, focused people, who think differently than educated people, are the ones who invent new products and services. Education can mess that up. “If you start having a high level of education, you start hiring people based on school success,” he said. “School success is predictive of future school success. You hire an A student if you want them to take an exam, but you want other things like street smarts. This gets repressed if you emphasize too much education.”

So think backward. Like Taleb, whenever you hear some “truism,” ask when that truism does not hold. Or ask whether the opposite might be true.

(10) Imagine something different. Sometimes the best way to think differently is to take in a scene and then subtract specific things from that scene. Imagine what the scene would look like if one object was missing or broken. Now imagine something else being missing or broken.

Imagine what a classroom would be like without the latest technology. Imagine what a city street would be like without sidewalks or benches or street signals.

On that last point, a number of European cities have removed stop lights in the hope of reducing the number of accidents at intersections. How can that be? Don’t red lights help to monitor street movement; don’t we need to make some cars stop so that other cars can go? In fact, with no street signals, drivers pay greater attention and learn how to cooperate better. Traffic management sifts from a command-and-control system to a cooperative system. Steven Johnson an experiment of a Dutch traffic engineer named Hans Monderman:

“As an experiment, he replaced the busiest traffic-light intersection [that handled] 22,000 cars a day, with a traffic circle, an extended cycle path, and a pedestrian area. In the two years following . . . the number of accidents plummeted to only two, compared with 36 crashes in the four years prior. Traffic moves more briskly through the intersection when all drivers know they must be alert and use their common sense, while backups and the road rage associated with them have virtually disappeared.”

Hans Monderman could create a real-world experiment to test his theory that less control produces more order. But you can create whatever mind experiments you want, to open your mind to new possibilities. The point is to get your mind to consider–and pay attention–to more possibilities.