Kate Daloz is the prototypical child of hippies—even if her parents abjure the term.

She grew up in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom when her family participated in the “back to the land” movement. As other Americans embraced the creature comforts and congestion of the suburbs, the Daloz family left to live independently among other naturalists, rebels, activists, and free lovers.

She grew up in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom when her family participated in the “back to the land” movement. As other Americans embraced the creature comforts and congestion of the suburbs, the Daloz family left to live independently among other naturalists, rebels, activists, and free lovers.

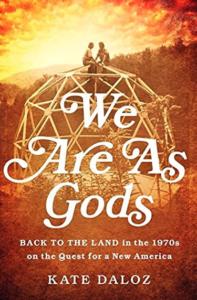

Daloz, the inaugural director of the Writing Studio of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences at Columbia University, tells the story in her 2016 book We Are As Gods: Back to the Land in the 1970s on the Quest for a New America, .

In her book, Daloz describes how her parents, Peace Corps veterans, joined their neighbors as they struggled with the realities of living on the land—from the long, hard winters and lack of indoor plumbing to the rivalries and resentments that result from the idea of free love. For some, the alternative lifestyle was inspiring and even life-saving; for others it was a long, hard grind bereft of the support they needed to live well.

Daloz received her MFA from Columbia University, where she also taught undergraduate writing. She was a researcher for biographers Ron Chernow (Washington: A Life), Stacy Schiff (Cleopatra: A Life), and Brenda Wineapple (White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson). She has written for The American Scholar, The New Yorker, and Rolling Stone, among other publications. She lives in Brooklyn with her husband and children.

Daloz visited my class “Writing the City” at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation to talk about the joys and frustrations of writing and her unusual childhood. Our class conversation went like this:

What do you write and why do you write it?

What do you write and why do you write it?

The common advice is to write what you know. But more important is: What are the deep questions that you don’t have answers for?

When I started writing my book about communes, I started thinking about the context where I grew up. My family was not interesting enough for an entire book, but the time period was. I was talking to my parents and they said, “Oh, you know, we weren’t hippies, but the people who lived on the commune next door, they were hippies.” Three groups of back-to-the-land newcomers lived nearby. They all showed up in northern Vermont within two years of each other in the early 1970s for the same type of experiment. I realized that this was clearly a historical moment that I hadn’t seen described anywhere.

This was a fleeting moment of experimentation. A lot of families like ours had gone back to the land. My family was pretty square but sex, drugs, and rock and roll–all of that happened at the commune.

I expanded the view outward from my parent’s little hill to three communes that were near each other. My parents belonged to a small community of couples living singly. A mile away there was a mini-commune with two couples living together and trying to farm with horses–in the 1970s, they had gone back to 19th century technology. And then a little further off there was the anarchic, free-love commune where they were really trying to live with no amenities at all. It was a very radical experiment with mixed results.

Once I looked at all three of these groups together, I could start to see the shape of the time period.

Your research eventually found a really specific focus—privilege among the utopians.

At the beginning, I thought, there’s the history of this period that has never been written. Later, I realized I was basically writing another book about middle-class white baby boomers celebrating themselves, which was not exciting to me.

Then, after reading an essay in The New York Times Magazine about privilege, I suddenly started understanding causal relationships that I hadn’t been seen before. The people that I’m writing about were incredibly privileged and they brought that privilege into these experiments in “poverty,” as they put it to themselves at the time. Their experiment was complicated by their own privilege and they didn’t understand that at all. That became by far the most interesting thing to me. Suddenly I had something new to say about this period.

They came from tremendous economic, racial, and educational privilege but were frustrated by what they saw as the limitations of Eisenhower-era American culture. They thought they could just wipe it all away and start a new society. The idea was, “We’re starting from scratch and everything is possible.” To some extent they were right. They threw out everything and in some ways never went back. One example: They decided they were against canned food and so they started to eat organic. If anybody had organic food for lunch today, it’s partly because of these guys. All kinds of stuff that came into the mainstream through the 1970s counterculture.

But sometimes in rejecting everything, they threw out too much. In the commune, they built a house with an open sleeping loft. The concept was, why do we need doors? They were also practicing free love and partner swapping. But not everybody was on board with that. People were telling me stories about having to be downstairs while their partner was upstairs with somebody else. And you could hear everything. There was no privacy. They kind of didn’t take their own emotions into account.

Over the course of research and writing a major project, your ideas are constantly changing, right? How do you focus so you can figure out what’s going to be the big idea?

I have learned to ask myself: What do you want your reader to take away from this? What do you want your reader to understand? What is it that you want for them? And then can you articulate that? Because if you can, then you’re in control of your material. I couldn’t answer these questions at the beginning of writing the book, but by the end I had a razor-sharp answer.

In my daily process, I often sit down in the morning and answer by hand for the section I’m planning to work on, “What do I want my reader to understand?” Even if I did the same thing for the same section the day before, it’s interesting to notice how sometimes the wording changes just slightly. It’s okay that it’s repeating, it’s okay that it’s recursive, because the important part is the process. By the end I’m going to have a really good answer.

The next question are: What are the details that the reader would need in order to understand this? What do I need to tell them about? It helps me make all those decisions that we have to make as writers. Do I tell them this? Do I go into this background? It helps me sort through all the things I learned doing research: Does this detail belong in the piece? Does my reader need this in order to understand? If they do, then you put it in. If they don’t, then it doesn’t go in.

Brainstorming and organizing ideas—figuring out all the pieces, how they fit, and what they mean—can be a crazy process. You can never predict how it might go.

Exactly. I’ve noticed that there’s a moment in my writing process when I can hardly sit in the chair, usually when I’m thinking about structure. So when I feel this happening, it’s more productive to allow myself to get up and walk and talk to myself. One time I was struggling with a structure problem when I coincidentally had to leave the house on an errand–I pretended to be on the phone and walked down the street talking to myself. It worked! I got there, and was like, okay, I solved that problem with the chapter. I wrote it down in my notebook so I wouldn’t forget, and then, you know, picked up my kid or whatever I was doing.

When I feel that restless writing stage coming on, I’ve learned to deal with it by treating myself like a bright but not very focused 12-year-old. I’m like, “OK, it seems like you have a lot on your mind. Let’s talk about that.” (This is me talking to myself.) I try to gently set boundaries on my own digressions rather than becoming severe with myself, since I find that entirely counterproductive to my productivity.

I’ve also noticed that understanding periods of restlessness and digression as part of my creative process can be really fruitful, so now I try to leave a certain amount of space for it.

At one point, I sat down to work on the book’s introduction and I could not focus. My brain was insisting on thinking about a different issue that had absolutely nothing to do with hippie communes–but did have to do with privilege. I finally gave in and hand-wrote an eight-page essay that never saw the light of day. It was strictly for myself. A week later it was like, Bloop! I realized, “Oh, this book is about privilege.” By not fighting myself [and telling myself], “Be on the same team as your own brain,” I let myself come to an interesting insight.

When you’re interviewing someone, do you direct them or just let them go off?

Within reason, let people digress. When you let people just talk, you start to hear what’s their agenda. If you give them some time, you learn a lot about what they want to talk about. And then you can take that lens and apply it back to what they told you and see if it changes your understanding of their narrative to some extent.

Tell me about your writing process? When do you write—and what’s your process?

The key part is just carving out time and just doing it. Someone once told me that keeping a journal doesn’t count as real writing because it’s not reader-facing. I find that to be a helpful distinction–to ask for a reader’s time and attention, you need to offer them something beyond what you’d write for yourself.

Before I was a writer, I was teaching adult basic education at LaGuardia Community College in Queens—really long days, but I loved it and didn’t have to work on Fridays. I always wanted to be a writer so I would use that Friday and sit down and make myself write. It was absolutely awful stuff. Then I started a writing group. On the strength of something I wrote there, I got into Columbia’s writing program. That program forced me to have deadlines and that taught me to make sure to block off writing time every day.

As far as my actual practice, I do a lot of work away from the computer. Especially in early stages, where I’m trying to articulate a big, new idea, I now spend weeks not typing at all. I sometimes write with a pencil on yellow legal pads. Very often the first draft happens there, then I type it and then it gets better. I did it this morning, actually. I often write in fragments, I do it in pieces. Over time, I start to see, OK, here’s how I would tell someone else about this. I spend a long time writing super informally.

Sometimes people think working by hand sounds inefficient, but for me it’s actually extremely efficient. When I’m writing by hand, I’m not sitting there in front of a blank screen, pulling my hair out, suffering. I’ve realized that sitting and suffering is the ultimate waste of time and that literally any other mode of working would be more effective. Now, whenever I write something on the computer and think, “Oh, this is awful, I hate it,” I just immediately close the screen and start writing by hand. Almost always, I move forward. I can’t tell you the number of times that’s happened. I just stop typing and start writing by hand and I’m free. I let myself make more mistakes and then I write 500 words that way. And then I come back the next day and type it up.

How do you sort your material so you can always find what you need?

I worked for two biographers, Stacy Schiff and Ron Chernow. They showed me how they organized research materials so carefully that their notes would still be absolutely comprehensible if they didn’t get back to them for a year or two, when it was time to start writing.

In my own, informal notebook, where I’m thinking through my central arguments, when something really good happens, I highlight it. So if I come back looking for that phrase or insight, I can find it. I make a list of notes that’s not linear, and not at all ready for a reader. Nobody should ever see it. It doesn’t look like final writing. It just is like fragments of phrases.

It just happened today. I’ve been trying to write a book proposal where I have to say, “Here’s my big idea and how to do it.” It’s hard to take something huge and express it in three sentences. So I have all these fragments of phrases and I printed them all out. And I look at them and I mark them up with a pencil—a pencil because that lowers the stakes, makes me feel like I can erase it and not lose anything–and gradually move them into a shape that will make sense to someone else.

Do you use any writing tools?

I use Scrivener, which lets you build folders. I like that you can compose in fragments, very moveable fragments. You’re not stuck thinking that you have to develop the whole piece from top to bottom. And for me, that’s really freeing.

On the research side, it offers nested compartments. I had one called “Myrtle Hill,” (the commune) and then a sub-folder called “physical layout.” Any time someone said something like, “you could walk from Lorraine’s tent to the cook tent” or, “you could see the outhouse from the road”—I copied and pasted those details into the “physical layout” folder so I would have them ready when I worked on that description.

How to you hunt for details—the kinds of “for instances” that surprise and enlighten the reader?

I used to do this exercise with creative writing students: Find a picture of a generic room, like from a magazine, and then decide something that might have happened there—somebody died or there was a birthday party, or whatever. Describe the room based on what you wanted the reader to think about that event. How do you describe the curtains if you want the reader to think about a party versus a death? This particular exercise leads to over-the-top descriptions, but the idea is how to get the reader to think about what you want them to think about even when you’re not describing action directly.

To write well you need to “start strong, finish strong” at every level—sentence, paragraph, section, and whole piece. How do you think about that?

The function of the beginning of a piece is to say, “Hey, reader, you were thinking about Spiderman a minute ago. Now I want you to think about this. Here’s all the things I want you to think about as you go into the meat of my piece.”

For me, I can’t get the opening right until later in the process. Once I know where I’m going, I can give somebody directions to where I am going. But I can’t give someone directions till I’ve gone there myself.

Clarity does not come in the beginning. I revise my way into clarity. I always ask myself, ‘What do you offer the reader? What do I want them to think about? Where am I turning the camera?’ Writing a strong beginning and end is one of my favorite things to do in revision.

When you’re describing something, you’re either slowing down something that’s really fast or speeding up something that’s really slow.

Sometimes you get to describe something in real time. Darcy Frey wrote a book about basketball called The Last Shot. The prolog shows his main character dribbling the ball. Frey just watches this kid at dusk dribble and then take a foul shot. The amount of time it takes to read the paragraph, that’s the amount of time covered in the scene.

I did something like that on an essay I wrote about the closure of the last roller disco in Brooklyn. I went to the rink and took my camera and filmed people. I knew I wanted to do something like Frey’s opening, so I found somebody in a red shirt and filmed them going around the rink once. Then when I was writing, I used that footage to help me build a one-sentence description of the rink that took that same amount of time to read. It was a long sentence, but it was a really fun exercise.

How do you speculate about something, when you only have scraps of information—but you want the reader to imagine a scenario?

I wrote an essay in The New Yorker about my mother’s mother, Win, who died of self-induced abortion in 1944. We have a ton of letters that she wrote, but none from the day before she died. I wanted to speculate about what was going on in her mind as she made an extremely momentous decision. So I say: “Win left no record of what she was thinking or feeling that weekend as the others tilled the garden while the children napped in a hammock. But when I imagine her, these are the things I think about: of how provisional and precarious early pregnancy feels…”

Also, when I wrote about her early pregnancy, I could say something because I knew what that feels like myself. The reader knows it’s me, it’s not her, in that sentence, and yet I want the reader to imagine what she was thinking.

What situations fascinate you, when you’re describing them moment by moment?

I like situations in which two things shouldn’t be true at the same time, but they are. One idea: Wouldn’t it be cool if you could find a situation where two people are doing the same thing, but one of them is doing it well and one of them isn’t? Like, you’re at the gym and there’s like a novice and an expert. Or two people fishing—one experienced, one doesn’t know much about what he’s doing.

Sometimes you need to use pictures—or even draw pictures—to understand them. You can’t just describe them, detail by detail.

When I was describing the commune, I had this map that someone else had drawn and then I walked around with her and took all these notes. Later, I drew my own crazy map that actually shows three time periods. Once I could do that, I was in control of the material. Once I could draw the map, I sort of kept looking at it to write. I eventually internalized it enough that I could just move around in that space comfortably, without looking at notes.

What’s the biggest difference between experienced and inexperienced writers?

Studies show that inexperienced and experienced writers work in different ways. Experienced writers did their work far from the deadline and under low-stakes circumstances. They use a notebook to develop big ideas, or talk a new idea through with somebody, or scribble notes on a napkin–their most important intellectual work starts far away from the version that a reader is going to see. By contrast, inexperienced writers tended to try to do everything at once in the final draft. They didn’t separate out stages of their process.

I never start the day typing, ever. I warm up with my notebook, because sometimes I just need to sit down and be like, “What am I doing?” or “Oh my God, this sucks, I’m so distracted.” That takes, I don’t know, like five minutes, before I’m ready to work more formally, sometimes more. Even if the warm-up takes a half hour, I get so much farther that day than I would if I sat in front of a blank screen for four hours.

How do you handle descriptions of long-ago events—when you can’t necessarily rely on the memories of the people you interview?

In a lot of cases, I was talking to people whose marriage had broken up, you know, or like two people who hadn’t spoken to each other in 40 years and they’re trying to remember the same thing. I tried to listen really hard for commonality. I also look for a contrast between their narratives. I also try to find the version that offers the details that are the most historically interesting. Then I see if I can corroborate those details.

How important is the title? And how do you come up with it?

I was with my editor and he told me, “OK, you need a title by Friday.” And I was like, “Cool, it’s Wednesday.” By coincidence, that afternoon I was looking through two versions of the Whole Earth Catalog, and I noticed that the statement of purpose in 1968 was, “We are as gods and might as well get good at it,” but by 1974 it had changed to include the line, “This might include losing the pride that went before the fall we are in the process of taking.”

That summed up the whole period for me, and many of the themes I was interested in exploring. Plus it looked really cool over an image of a half-built geodesic dome.