In another post, I describe the importance of finding The One Idea for everything you write.

In another post, I describe the importance of finding The One Idea for everything you write.

I have both succeeded and failed in this quest.

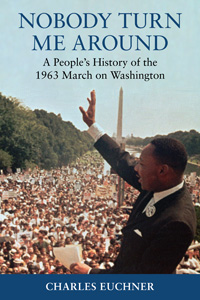

Success: Nobody Turn Me Around

About a decade ago I was in the midst of writing a book about the 1963 March on Washington. At the same time, I was maniacally studying the elements of writing. I devoured books and articles about the brain, learning, memory, storytelling, and writing mechanics. I looked for any and all insights that would give my book the drama that the subject demanded.

That’s when I first realized the importance of The One Thing. The brain, research shows, simply cannot manage more than one idea at a time. Sure, as research in the 1950s showed, people can remember a list of seven ideas or things. But that doesn’t mean they can do anything with those ideas. To really act in the world, people need to focus on one thing.

That’s when I first realized the importance of The One Thing. The brain, research shows, simply cannot manage more than one idea at a time. Sure, as research in the 1950s showed, people can remember a list of seven ideas or things. But that doesn’t mean they can do anything with those ideas. To really act in the world, people need to focus on one thing.

At all levels of my book, Nobody Turn Me Around (Beacon Press, 2010), I tried to identify The One Thing that should serve as a North Star for readers. Here’s what I came up with.

The book

The One Idea, driving everything else in this book, is this: The March on Washington was essential to hold together the disparate factions of the civil rights movement, at a time when support was fraying for the movements integrationist and nonviolent ideals–when President Kennedy’s civil rights bill offered an opportunity to create historic reform.

The book explores all kinds of issues, but they all relate to the need to hold the movement together.

This throughline animated every action of the movement’s organizers (Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, Martin Luther King, Roy Wilkins, and others) and allies (Kennedy, congressional supporters, leading celebrities, ministers, organizers, and more). It also animated the opponents (like Strom Thurmond and other congressional segregationists, conservative intellectuals, the FBI, and others), who worked to divide the movement.

The parts of the book

The book had five parts, mirroring Aristotle’s narrative arc. Each section had One Idea:

1. Night Unto Day: In the wee hours of August 27, 1963, people made their final movements to the march. Dr. King prepared his speech, ignoring advisors’ counsel to avoid talking about a “dream.” Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin set the march’s goal: to put the movement’s bodies on the line to force Washington to act–and to do so nonviolently. Meanwhile, thousands streamed into the capital, with varied values and goals but a commitment to following the movement’s highest ideals and to ignore figures on right and left who would divide the movement. The One Idea: United, we stand.

2. Into the Day: As people arrive at the Mall, the systems are in place for a successful march. bayard Rustin successfully managed all the logistics, as did the Justice Department. The One Idea: Plan it right to avoid problems.

3. Congregation: As the March on Washington began, the movement’s far-flung members were on full display. They came from all walks of life, from all over the U.S. and beyond. They included rich and poor, intellectuals and laborers, blacks and everyone else, radical and moderate, Northerners and Southerners, religious and nonbelievers, believers in nonviolence and “any means necessary,” and more. The One Idea: There is unity in numbers and diversity.

4. Dream: After performances from musicians and speeches by notables, the afternoon program began. Each of the ten leaders of the March offered their own perspectives, from a faith-based confession of apathy (Matthew Ahmann) to a youthful cry of impatience (John Lewis) to a movement veteran’s call for reform (Roy Wilkins) to a labor leader’s warning about America’s world reputation (Walter Reuther) to an urbanist’s call for jobs and opportunity (Whitney Young) … to the transcendent call for a dream (Martin King). The One Idea: Civil rights is the underpinning of all progress.

5. Onward: At the end of the day, everyone returned home, determined to fight for civil rights in their communities, aware that that fight would be long and hard. The One Idea: Struggles require fighting hard, not just expressing grand ideals.

Each section has One Idea. Each of those ideas, in some way, supports the book’s One Idea.

Fragments in the book

Each of the parts comprises a number of smaller pieces–what I call “fragments,” vignettes and background information. Fragments range from a page and a half to nine pages. Each fragment advances the One Idea of the section, and therefore the One Idea of the book.

Let me mention a few examples–the sections that offer portraits of Phil Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and Martin Luther King. Each brought an essential quality to the civil rights movement. Randolph insisted on mass demonstration. Rustin insisted on nonviolence. King understood that the movement had to be transformational, inspiring courage and commitment.

Those three forces–body, mind, and soul–were essential to pursue the movement’s long-term strategy. They were also essential to hold the movement together (the book’s One Idea).

Paragraphs and sentences in the book

Every paragraph and sentence also contains just One Idea also. This is important. All too often, writers treat the paragraph as simply a container for a bunch of ideas. In his book on writing, Steven Pinker actually argues that “there is no such thing as a paragraph.” When we break the text into paragraphs, Pinker says, we’re doing nothing more than providing “a visual bookmark that allows the reader to pause.”

But that’s not right. When you look at great writers, from Hemingway to McPhee, you see how they state and develop just one idea per paragraph. In my classes, I require students to label each paragraph with a “tabloid headline.” That way, they learn not to stray off course. If anything in the paragraph does not address the label, it’s gotta go.

I’ll offer just one paragraph from my book, about the writer James Baldwin, for illustration:

In all of his years in the U.S., Baldwin struggled to understand his own alienation. “It was in Paris when I realized what my problem was,” he told the New York Post. “I was ashamed of being a Negro. I finally realized that I would remain what I was to the end of my time and lost my shame. I awoke from my nightmare.” The whole race problem, Baldwin argued, required the same kind of rebirth nationwide. But he despaired that such a rebirth would not occur. Black communities from Harlem to Watts were committing slow suicide with violence, drug and alcohol abuse, violence, and alienation from schools and jobs.

My tabloid headline for this paragraph would be “Alienation of All” or “Split Souls” or some such. By the way, that paragraph speaks to the One Idea of the book, its section, and its fragment.

Think of each One Idea as part of a Russian nesting doll. The One Idea of the whole piece contains The One Idea of all its smaller parts.

Failure: Little League, Big Dreams

I didn’t fully understand The One Idea when I write a previous book about the Little League World Series.

Originally, I hoped to present the drama of the LLWS the way the documentary Spellbound presented the National Spelling Bee. I wanted to show different contestants prepare and then advance through many rounds until the drama of the final competition.

And so I tracked the monthlong Little League tournaments, from districts to states to regions to the final tournament in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Along the way, I found some great stories and explored some fascinating issues. When it was over, I spent time in the hometowns of the two finalists in Ewa City, Hawaii, and Willemstad, Curacao. I learned lots more.

And so I tracked the monthlong Little League tournaments, from districts to states to regions to the final tournament in Williamsport, Pennsylvania. Along the way, I found some great stories and explored some fascinating issues. When it was over, I spent time in the hometowns of the two finalists in Ewa City, Hawaii, and Willemstad, Curacao. I learned lots more.

Then I started writing. I liked what I wrote, mostly anyway, but it lacked the power and drama. The deadline approached and I turned in a draft. My editor liked it. We debated titles. We settled on Little League, Big Dreams. I didn’t like the title; it seemed too mushy and too upbeat for the story I wrote. But the publisher gets the final call on titles. So we passed the manuscript to a line editor.

Then I had a eureka moment. I realized that one word captured the essence of the book. I called my editor. “Can I have more time?” I said. “I figured out what it’s about–hustling.” The book was about the kids’ hustling, their dedication and earnestness, their willingness to work hard for something. But it was also about a more negative form of hustling–coaches manipulating rules, driving kids too hard, helicoptering and bullying parents, Napoleons who run the local leagues, pressure from sponsors, the glaring spotlight of TV. I wanted to give the book a simple title–Hustle or Hustling–and realign the text to tell that story. It would have taken just a week.

The answer was no. “We’re too far into this,” he said. “Sorry.”

Without The One Idea, the book was a mishmash. One reviewer said it was like a long Sports Illustrated article, not a book. She was right. Books gain their power when they state and develop One Idea, with a variety of stories and exposition.