An old TV commercial for Berlitz showed the training of a German coast guard watchman. The supervisor shows the new man all of the monitoring equipment and then leaves him alone to man the controls.

Later, a distress signal comes in: “SOS, we’re sinking! We are sinking.” The new watchman is confused. “What are you sinking about?” he asks.

Success and failure in communications often depend on a single word—even a letter or two. The way most people write today—in business, education, government, even journalism and publishing—is the result of an accidental, ad-hoc process of learning and mislearning. We need a better way. And the emerging science of reading and writing offers the path.

These days, everyone is a writer. A survey of Fortune 500 companies found that 70 percent of professionals must write on the job. And when they’re not writing, they’re reading their colleagues’ writing. My father, an engineer, could get away with not writing. So could most other professionals—developers, bureaucrats, scientists, philanthropists, business people. few people ever had to write a generation or so ago. And when they did write, they didn’t have to write much.

Old, Failed Approaches

So we’ve never had a fail-safe system for teaching and learning how to write. Writing instruction—in school, in business, and in writing seminars—takes two opposing approaches.

First, there’s scolding. Rather than showing us how to master all the discrete skills of writing, teachers shake their heads and wag their fingers and fill our drafts with red ink. So you’ll get back a draft with remarks like: Don’t you know about passive voice? This passage is awkward. Get the punctuation right. This is not a good topic sentence. Avoid run-on sentences. I need better evidence. What’s your thesis? Too often, these comments do little more than tell you what’s wrong. They don’t tell you how to make it right.

And then there’s coddling. Ever concerned about encouraging students, the coddler sets no standards at all. So you’ll hear teachers say, in one way or another: Anything you write is great, because there’s only one you! Don’t worry about punctuation or grammar or getting the words just right. Just write! You get this approach in “creative writing” and other programs designed to encourage students to explore. Nice idea. But it doesn’t work.

Neither of these approaches breaks writing down to its basic skills, and shows the learner what to do, step by step. Imagine if we learned other skills—like how to drive a car—the way we learn how to write.

Scolding: What’s wrong with you? Just drive? Don’t ask me how! Just move the car into traffic, without lurching or hitting anyone. And when you parallel-park, don’t ask me how. Just do it!

Coddling: Whatever way you want to drive is just fine! You’re special! There’s only one you! Don’t worry about those other drivers! So what if they can’t figure out what you’re doing. Just keep driving. Marvelous!

When you learn to drive, you break down every move into pieces. Then you practice—intently—until you get it right. You focus on one skill at a time, until you get it just right. You get instant feedback, not just from the instructor but also from other drivers and the car itself. If you stall, you know you did something wrong. You also learn that you need to care about others on the road. More than anything else, you learn to manage your own mind. You learn how to pay attention, how to be a “defensive driver,” how to compensate for blind spots.

Go With the Brain

We need an approach like that for learning how to write. Luckily, the burgeoning research on the brain—on cognition, attention, learning, skill-building, problem-solving—offers powerful insights for mastering the writing process.

When I’m teaching writing—to high school and college students, teachers, business people, social workers, and other writers and editors—we explore “what the brain wants.” The brain is the boss of everything we do. If you work at cross-purposes with the brain, it will not perform as well as possible. But if you give the brain what it “wants,” you’ll succeed.

Over the last generation, we have learned more about how the brain works than ever before. And so we know “what the brain wants.” And what the brain wants, you better give if you plan to connect with your audience—whether it’s your colleagues inside the organization or your clients, vendors, policymakers, industry leaders, or the buying public outside the organization.

What Does the Brain Want?

So what does the brain want—and what doesn’t the brain want? And how can that knowledge guide our development as writers?

The brain wants:

Clarity and guidance: We need to know where we are. We hate getting disoriented or lost. So you need to tell the reader what she needs to know, as quickly and as simply as possible.

Predictability, reliability, and patterns: Everyone wants a sense of where they’re going—without having to pay too much attention. If we had to process all of our sensory inputs, we’d explode. One researcher calls the brain a “prediction machine.” We need to assess not just what’s going on right now, but also what’s about to happen.

Specificity: The brain wants specific images, sounds, and ideas. The more vague we are, the more unsettled and disoriented we feel. But when we get specific information—not just the five W’s (who, what, when, where, and why), but also the one-and-only details that set them apart, we are engaged. “Mississippi” tells more than “big river”; “Aristotle” reveals more than “Greek philosopher”; “double helix” says more than “genetic structure.”

Change, action, and surprise: Our brains evolved to detect change. If we’re foraging for food, we need to notice when a predator lurks. When something surprising happens, we jolt into a heightened state of attention and readiness. Because action activates all our senses—sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste—we come alive when we see action.

Completeness, closure, and wholeness: We need to know “how it all turns out.” Nothing nags at our consciousness—and drains our energy—more than an unresolved problem. When we solve a problem or answer a question, we feel immense satisfaction. Only when we finish something do we feel we can move on.

Look closely at these desires. You might notice that they’re also the elements of stories. Humans are, in fact, a storytelling species. Nothing sets us apart from other species more than storytelling. Other species eat, drink, sleep, find shelter, reproduce, and even use tools and language. As far as we know, only humans tell stories. Stories excite and engage us; stories create order and make sense of the world. we could not live without stories. Luckily, everyone loves hearing and telling great stories. We’re wired for narrative.

The Brain Wants a Story

Now, let’s get back to writing. What does this tell us about the best way to master writing?

Simple: If you can master the skills of storytelling—and, as part of the process, give the brain what it “wants”—you can write well. And you can have fun in the process.

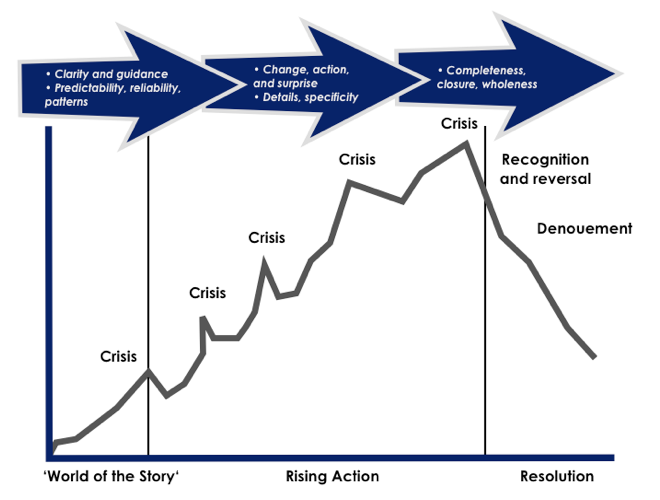

Storytelling has a simple structure, which Aristotle outlined in The Poetics 2,500 years ago. Aristotle called it the “narrative arc.” Every story, Aristotle taught, has three parts. In Part 1, you get to know the world of the story—the characters, where they live and work, their values and desires. In Part 2, you see the hero (and other characters) struggle to achieve his goal. Along the way, he faces greater and greater barriers. As the story progresses, the character learns more and more about how the world works and about himself. Finally, in Part 3, the hero comes to a new understanding about himself and the world. Aristotle calls this “recognition.” Once the character reaches this greater understanding, he “reverses” himself and sets out to live life in a new way. The story winds down.

You can see the narrative structure—and the five basic needs of the brain—in this graphic:

This three-part structure of storytelling reveals the basic structure of all writing. Every element of writing—the sentence, paragraph, section, chapter, article, story, analysis, and so on—takes this basic 1-2-3 structure. In a sense, everything you’ll ever write is a story. Once you master the basic structure of stories—and some simple, specific strategies for building stories—all the other challenges of writing come easily.

I have seen poor and mediocre writers become strong writers in a matter of weeks by applying this system. I have seen good writers become masters of the craft. If it sounds too good to be true, it’s not. Remember, we are all born storytellers. Storytelling is part of our DNA. Storytelling is as natural for us as eating and drinking.

When we teach people how to write with this natural system—this brain-based approach that’s already built into our brains—we will become a world of skilled writers. Why not? It’s who we are.

For more posts on writing, visit the Elements of Writing Blog. Check out the posts on Storytelling, Writing Mechanics, Analysis, and Writers on Writing.