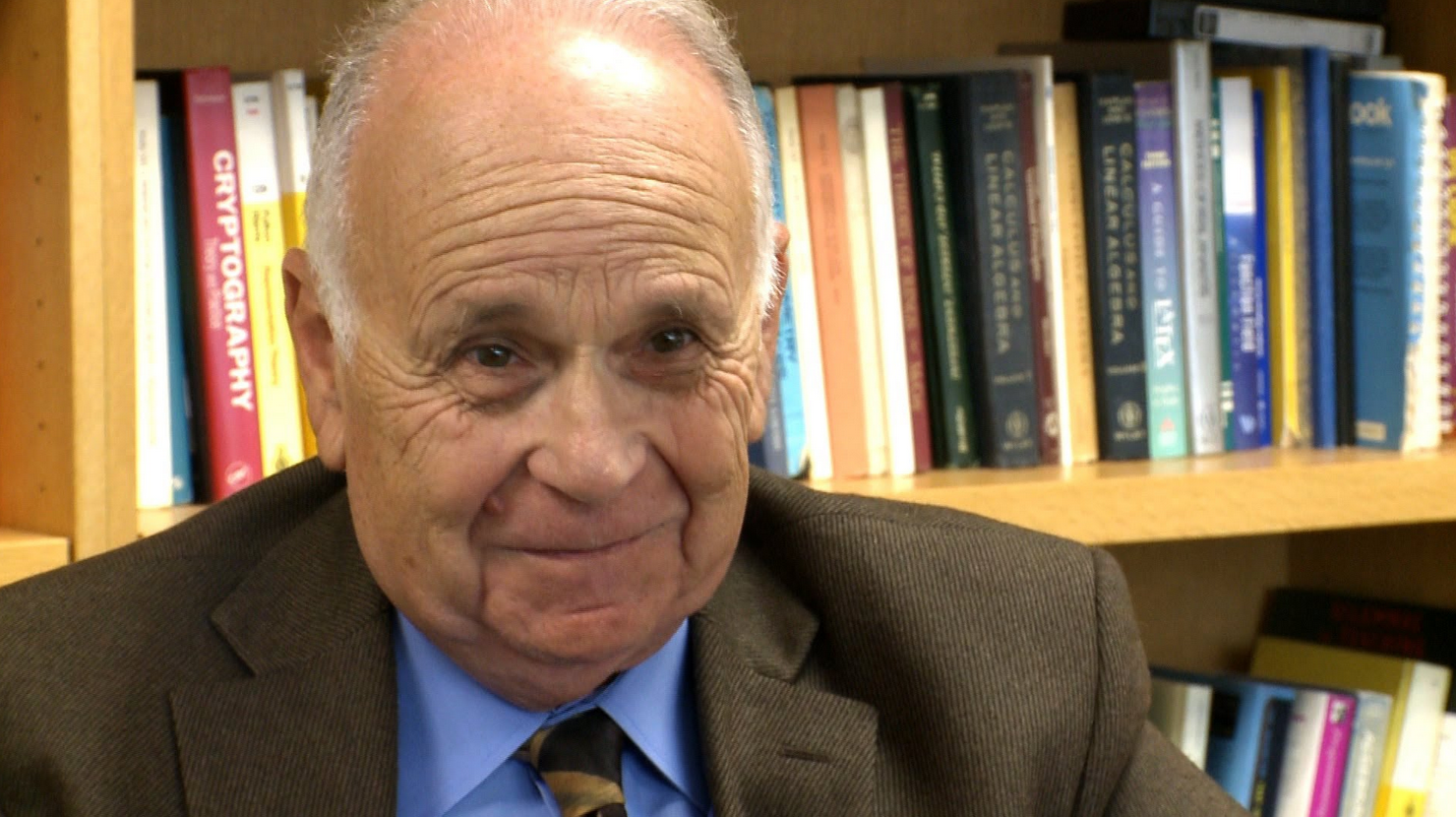

Paco Underhill, the son of a diplomat, turned his liabilities as a boy into his greatest assets.

Underhill grew up on the move as his father took new postings with the State Department. Living in Poland and Malaysia, he did not experience the retail riches of Western life. Partly because of his itinerant life and partly because of a childhood stutter, he learned to observe his surroundings carefully.

Underhill grew up on the move as his father took new postings with the State Department. Living in Poland and Malaysia, he did not experience the retail riches of Western life. Partly because of his itinerant life and partly because of a childhood stutter, he learned to observe his surroundings carefully.

He developed those powers of observation even more acutely as a city planner, working for the Project for Public Spaces under the direction of the legendary William (“Holly”) Whyte. Underhill then created a consulting firm called Envirosell that analyzes how people use stores, museums, and other public and private places. Using direct observation, time-lapse photography, interviews, and data, Underhill and his team identify ways to make the shopping experience more engaging to users and more lucrative to retailers.

Since its founding in 1986, Envirosell has worked in 50 countries and with more than one-third of all Fortune 100 companies. He has worked in all sectors, in virtual as well as brick-and-mortar environments.

Underhill’s new book How We Eat offers a friendly guide not just to the shopping experience, but also to the larger issues of food, e.g., organic versus mass farming, small versus supermarket buying, home cooking versus prepared foods, and varieties of diets and eating traditions. Like his previous books—Why We Buy, Call of the Mall, and What Women Want—How We Eat offers insights into the everyday design decisions that shape human behavior.

Winston Churchill once remarked: “First we make the buildings, then the buildings make us.” Underhill offers a methodology for remaking the spaces of our lives. The $1 trillion food industry makes us, for sure; but with the right insights, we can also redesign the systems that produce and sell food

Underhill, a graduate of Vassar College, lives in New York City and Madison, Connecticut.

You started your career as a city planner and analyst—using time-lapse photography to track how people behave in public spaces. How did that come about?

I went to Columbia for a summer and in one of my classes heard a lecture by Holly Whyte. As I walked out, I thought, “Man, this is so cool.” It was a way to observe people and understand how the built environment worked. It made complete sense.

After I heard him lecture for 45 minutes, I knew what I wanted to do. And then I ran my own study. I looked at a pedestrian mall in Poughkeepsie and how the street furniture and signs worked. Then I knocked on his door: “Hello, you don’t know me, but I just did this…” That’s how I got my first job. That’s when the Project for Public Spaces was just launching. I became the first staff member. One of my first jobs was working at Rockefeller Center.

Holly Whyte was a magical guy. He had a gift of gab. I saw him entrance people at least 100 times after that first lecture. I learned about how he wrote and presented himself.

How did you make the transition from city planning to retail analysis?

I was a junior member of a crew that would go to different cities and look at traffic patterns and rewrite zoning ordinances. I was on the roof of the Seafirst Bank building in Seattle, 60 stories up, and there was a stiff wind blowing. My job was to install cameras and I could feel the building rocking. I did what I had to do, but I would rather have a job where I don’t have to go into the roofs of buildings.

A week later I was in a bank and getting madder by the moment and realized that the same tools I used to explore cities, I could use to understand a bank or a store or an airport or a museum or a hospital and deconstruct how they worked. I had never worked in banking or retail or even took a business course. But I knew something about how to measure how people move. It also helped that I came to it with a certain degree of freshness.

A lot of observations seem obvious after the fact—but they are fresh insights at first.

One of my jobs was analyzing a Burger King and its new salad bar. It was in the early 1980s in Miami. Yes, my job was to look at the salad bar, I was going to look at the entire pad. There were so many things that were painfully obvious, but to the marketing research team, were just completely new and different. When a man walks into a Burger King, the way he chooses a table is different than the way a woman does it. We tracked who parks in the lot and who goes through the drive-through. If you drove a Cadillac, you would use the drive-through. That’s obvious but no one had noted it before.

There are implications in terms of design and management. I started with restaurants, then worked on hardware stores, music stores, fashion, then food. I was able to come up with [store design changes] that someone could do in a week or two or even overnight. Business in those days was focused on strategy—McKinsey, Boston Consulting Group. I was able to say, “Here are five things you can adjust and make a difference.”

Some of it was comic. The first hardware store, I said the brochures are in the wrong place. They let me move them but at the end of the first day the manager yelled at me: “You’ve gotten rid of a week’s work of circulars in one day!” One of the first drugstores, I asked, “Why are the baskets only at the front door?” I showed them video clips with customers walking to the register with their arms full. What if we trained staff so that when they see someone with four things in their hands, the customer would get a basket? We did it and the average purchase went up 18 percent.

How did you learn how to observe carefully?

Growing up I had a terrible stutter. As we moved every 18 months or two years, I was more confident looking and trying to understand how things worked than asking questions. So I took a coping mechanism and turned it into a profession.

I also remember looking at Sears and Roebuck catalogues—toys and furniture and all these things. Nothing in Warsaw duplicated that catalogue. Going into Germany during a family trip, getting into the first PX, it was a world I had never seen before. I am not a material kind of guy, but I do have a passion about understanding how things work.

How can we train ourselves to make careful observations?

When I taught field work at City University, we were right across from Bryant Park. I would pick one person from the class and say, “I want you to go and walk around Bryant Park for 15 minutes and come back and tell us what you did. After he left I would pick out someone else and say, “I want you to go follow him and record what he did.” Then they would come back and we would contrast what the two reported. There were obvious differences. People didn’t lie but what they said and did was often completely different.

What kinds of habits—and what kinds of people—make for good observation?

Over the last 34 years I sent out crews of trackers all over the world. When I’m in an environment observing, I have to be very careful after doing it for an hour—I haven’t seen what I need to see. It’s often the second or third day when you really see and understand. So a lot of it is a Zen-like state of patience.

One man did 500 missions for me. He had a short career as a guitar player in a prominent early 90s band called Codeine. It had its own distinct beat. He became a kindergarten teacher. I found him doing substitute teaching and he was so patient and so observant and so rhythmic, with a slow steady beat, and he was so empathetic.

I also had an Endicott Prize-winning illustrator of children’s books. He would work for me for nine months and then he would come in and say, “Disney just optioned one of my books, I need to take some time off.” So he would go and then come back when he was ready. I would rather have someone great for 60 percent of the time than someone not as good 100 percent of the time.

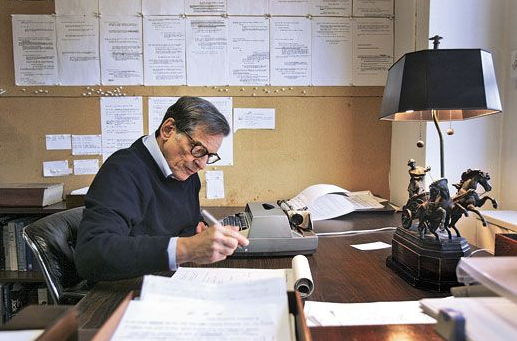

How did you develop as a writer? How did you develop your informal, avuncular style?

In my early college years, I had a wall in my dorm filled with rejection letters. I wrote stories and even poems. I wrote fiction into my 20s. I took the skill set I learned writing fiction and used it in my nonfiction writing.

There are nonfiction writers who are trying to show how smart they are. I firmly believe in edutainment. If I can entertain you, I can educate you. I want to change readers’ prescriptions [lenses] in how they see the world.

How do you break down and manage major writing projects?

I have always been a writer of columns. The form I feel most comfortable is a 2,000- to 3000-word piece. People’s attention spans aren’t the same that they were when Charles Dickens wrote his books. Therefore, when I think of a book, it isn’t 12 chapters, it’s actually 50. I’ve broken it down so it’s easy for someone to pick up the book, read for a while and put it down and not feel as if they’re missing anything.

To write How We Eat, I had 40 columns, 50,000 words already written. It was a matter of piecing them all together. I learned from writing reports, it’s important to create a framework to start out. It isn’t as if you start at the beginning and go to the end. Get a frame and put pieces into that frame.

The modern book isn’t measured in pages; it’s measured in words. I was informed early in my career that to get read, a book needs to be 70,000 words.

Also, I also recognize that I need to keep vocabulary simple. As a column writer, I’ve been very careful about use of adjectives and adverbs. I should say careful, not very careful.

I have always been a storyteller. Being able to take business or nonfiction knowledge and do it as a story is very reader-friendly. There are a couple of sections where it goes from being a monologue to a dialogue. That’s part of what pleased me—the transition between one and the other. It makes it m more informal. It’s storytelling.

What writers have you admired and emulated?

I always loved the fiction writer James Lee Burk. He could describe smell better than anybody I knew. His books are formulaic, but he can go on for 1,000 words describing a smell.

Then there’s the foreign service man, Edward Hall, who write The Hidden Dimension and The Silent Language. Growing up in a third world country, even as a teenager I didn’t have TV. I consumed a prodigious amount of books—60 to 80 a year.

How did How We Eat develop?

When COVID hit, I had been working on the manuscript for over a year and had to take 60 percent and throw it out. A year ago, after having been battered by COVID, I gave Envirosell to my young employees and shifted to being a strategic advisor. That means my platform is a lot freer because I don’t have to worry about stepping on toes.

This book feels lighter—the style and flow and personality—than Why We Buy. Am I right about that?

That’s a very conscious effort. The purpose is to get to a healthier version of ourselves and our planet. I’m not going to tell you what to do but I can change the prescription [lens] by which you see the world. In changing that, you able to make better decisions. I was also aware I wanted to write for a popular audience. Everybody eats and drinks and buys food and beverages. Why We Buy targeted a certain audience and What Women Want targeted a specific audience. This one was targeting everyone.

Hollywood uses the “logline” to describe the essence of a film—a simple one-sentence line about the major character or mission. What’s your logline?

Mine would be: I want to change your prescription to get to a healthier version of yourself and create a healthier planet.

When COVID hit, we recognized that the world was going through a fundamental change. It wasn’t World War II breaking out, but it was global and there was a great deal of hurt. And it affected the structure of our own lives. I realized I don’t want to write a negative book. I don’t want to say, “Oh, man, are we screwed!” I wanted to write a positive and enlightening and challenging book.

The word I kept using is “post-pan.” I want to focus on the post-pandemic period. It will be over at some point. There are going to be some big changes and we need to be ready for them.

Most programs don’t offer much good advice. Where I went, I heard “Don’t get it don’t right–get it done” and “Say what you’re going to say, say it, and say you said it.” Not terribly helpful.

Most programs don’t offer much good advice. Where I went, I heard “Don’t get it don’t right–get it done” and “Say what you’re going to say, say it, and say you said it.” Not terribly helpful.

To get this right, adapt Mark Twain’s dictum–“When you catch an adjective, kill it”–to your comparisons. When you catch a fleeting pop-cult reference, kill it.

To get this right, adapt Mark Twain’s dictum–“When you catch an adjective, kill it”–to your comparisons. When you catch a fleeting pop-cult reference, kill it.

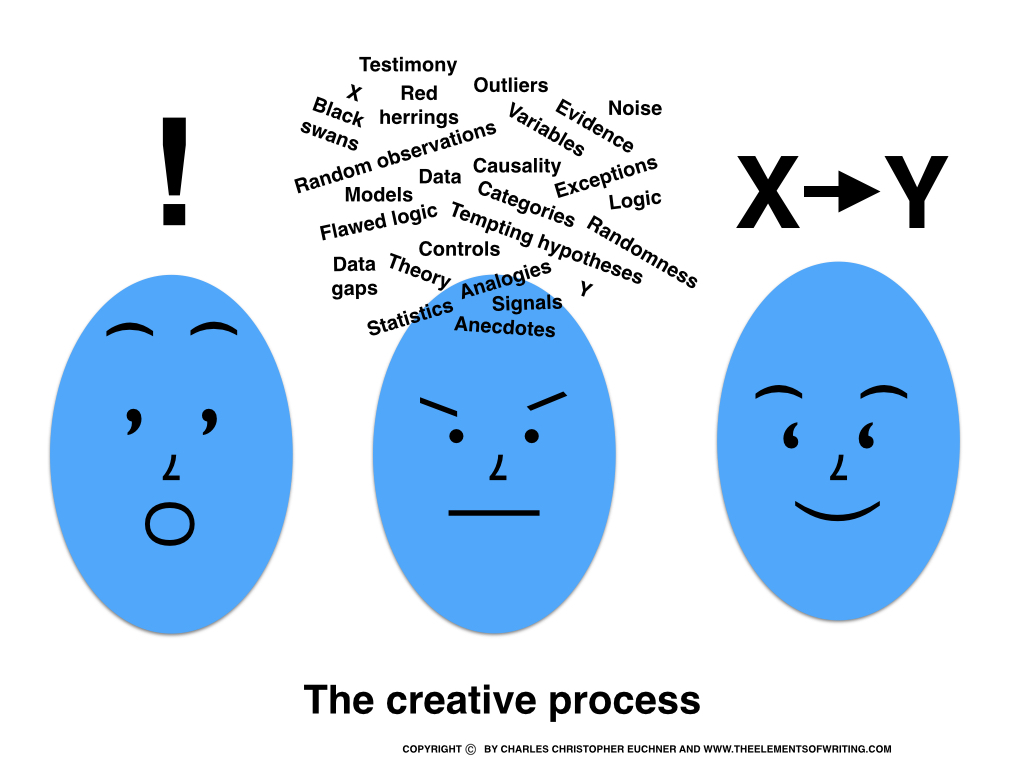

This is, of course, a false dichotomy. It’s not a matter of either/or. It’s both. So we need to understand how the mystical and the grinding come together.

This is, of course, a false dichotomy. It’s not a matter of either/or. It’s both. So we need to understand how the mystical and the grinding come together.

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.

Yes, we’re talking about brainstorming. It’s a process of searching your whole mind, with few preconceived ideas about what you want to say. It’s a way of digging deep. It’s a process of discovery.