Harry and Mary were still working at the Supreme Court Justice’s apartment when I arrived. Harry asked to see my calling card.

“My what?”

“Why, your calling card, of course. And if it doesn’t look just right, you’ve got to have a new one printed.”

“Why, your calling card, of course. And if it doesn’t look just right, you’ve got to have a new one printed.”

I laughed and said, “I don’t have any calling card. I never did have one. Where I used to live we just didn’t seem to need calling cards, and when I got to Harvard I never bothered to have one made up..”

“Lord Almighty!” gasped Harry. How do you think you’re going to get along in Washington without a calling card? Where do you come from, boy?”

The Forgotten Memoir of John Knox

When a young man named John Knox traveled to Washington and went to the chambers of Supreme Court Justice James McReynolds, he might as well have been invisible. He didn’t bring a calling card.

In those bygone days, newcomers carried cards to introduce themselves. A calling card symbolized professionalism and stature. Without a card–preferably, an engraved card–the job seeker was considered gauche and inadequate.

These days, we use cover letters in place of calling cards. Cover letters introduce the job-seeker to the employer, with the hope of beginning a conversation about employment.

Most cover letters are bad. Bland and unfocused, they say too much that employers don’t care about–and too little that employers actually want to see.

A great cover letter offers direct, tangible proof that the job seeker can help the employer do something important, with a minimum of fuss and the potential for something great.

1. The Power Of A Cover Letter

Almost always, the cover letter provides the first encounter between employer and job seeker. In lieu of a real, face-to-face introduction, the cover letter gives you the chance to say who you are and why you can help.

Unfortunately, most cover letters disqualify the job seeker. Bad cover letters show that the candidate lacks the professionalism, rapport, relatability, or skills to do the job. And so they go straight to the reject pile.

If the candidate is qualified, a good cover letter will prompt the hirer to look more closely at the resume–and to invite the candidate in for an interview.

The best cover letter reveals something–not everything, but something–about your essence as a person and as a professional.

The cover letter offers an opportunity to step outside the details of your career and education and accomplishments and speak–intimately, one on one–to the potential employer. You can begin to forge a human relationship with the hirer, to indicate the specific ways in which you might her life better.

What do I mean by “essence”?

The essence of something is its most distinctive qualities. After you have cleared away all the details, the timelines and projects, and all the distractions, the essence is what remains. When you see someone’s essence, you say: Ah yes, I get this person. I understand this person’s critical values and attributes.

You can find a person’s essence in a story, an experience, a project, or a relationship.

If you’re seeking a job, you want to show your essence in a way that makes the recipient visualize you on their team.

2. Do Research Before You Write A Word

Hate to tell you, but you have lots of work to do before you even think about what you should write.

Before you present yourself, you need to educate yourself about the jobs in your field and how they align with your own background. And you need to find language that shows the obvious connections between your profile and their job.

• Create an Inventory of Skills and Values–But Focus on Accomplishments

Take a piece of paper and create three columns–one for skills, a second for accomplishments, and a third for values.

If you have a good resume, this should be easy. But don’t get lazy and reply on the resume. Create a completely new document using these categories.

Write down everything you can say about yourself for each category. Get everything down. Even if you’re iffy on a skill or accomplishment, write it down. You can cut it later.

Then translate these listings into something specific, something tangible and visual.

We have a tendency–especially in academe and the professions–to use abstractions. That’s fine; buzzwords offer a great shorthand for interacting with colleagues. But when you reach out to a potential employer, you want to help them to see you.

Let me repeat that for emphasis: When you reach out to a potential employer, you want to help them to see you. Our brains come alive when we can visualize something. If I say “social justice,” it doesn’t mean much; but if I say “run community meetings” and “conduct surveys to gather community input” or “serve on a grassroots committee on water runoff,” the reader can picture me doing these activities.

So rephrase every abstraction on your three lists. Show what that abstraction means with phrases that show you doing something. Don’t say “data specialist”; say, “At Place X, at Time X, I used Tool X or Process X to examine Trend X or Problem X.” All those X’s refer to specific things. They are visual. They allow the reader to see you in action.

• Research Job Sites

Don’t just randomly search for jobs and then respond. Instead, do a complete search of all the possible jobs that you would like to win.

Start by going to the online sites. If you have a good presence on LinkedIn, try thyat. Also go to Indeed.com and Grassdoor.com.

Enter all the words that describe your skills and interests.If you’re a city planner, type words like planning, planner, geography, GIS, environment, housing, city, urban, parks, streetscape, urban village, transportation, transit, TOD, streetscape, neighborhood, and grassroots, to name a few.

Use only the terms that speak to your skills, experience, and values. You don’t want to apply for a job that would make you miserable. Don’t search “grassroots planner” if you hate community meetings; don’t search “GIS” or “quantitative” if you hate spending hours crunching data at your desk.

Save the job listings that might be interesting. The best approach, in my experience, is to bookmark the posts in a special folder called “Job Search.” (If you don’t know how, click here.)

When you have identified jobs that sound intriguing, look for the keywords in the ads. Write them down.

• Compare Attributes–And Identify The One Thing

Now finding the right jobs is a simple matter of comparing your attributes with the job postings’ key words. Decide which jobs you might want to get. Take a job’s key words and figure out how you might want to pitch yourself.

Here’s where it gets tricky. If you’re applying for a professional job–even an entry-level job, after college or grad school–you probably have lots of interests and abilities. That’s great. But when you seek a job, you cannot list all those attributes in a cover letter. A cover letter has to be short.

Your cover letter should give the recipient a clear vision of the superpower you bring to the job. A Russian parable goes: “When you try to catch two rabbits, you don’t catch either.” If you use a cover letter to list all your attributes, you will fail to convey your essence–what makes you distinctive and special.

So identify the ONE Thing that you want the reader to see when considering your application. (For more on “The One Thing,” see this recent post.)

• Do Not Just Restate the Resume

When you apply for a job, you almost always provide both a cover letter and resume. The cover letter offers a way to make a quick hello–and to distinguish yourself from the hundreds or even thousands of other candidates.

Many candidates are tempted to offer a complete summary of their careers. They list jobs, responsibilities, projects, and results. They often quote people praising them. Often–way too often–they use bullet lists to show the range of experiences and skills.

Some people use the cover letter to review the resume. That’s a mistake–usually a fatal mistake. Hirers can read your resume. If you have created a good, well-formatted resume, they can get a sense of your career, skills, and aspirations in a matter of seconds.

Don’t do that. That’s what a resume is for.

3. A Minimalist Approach?

The best advice you’ll ever get about writing comes from Polonius, a character in Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

Polonius, the father of Laertes and Ophelia, says: “Since brevity is the soul of wit / And tediousness the limbs and outward flourishes, I will be brief.”

Good idea. Keep it simple. Keep it short. But how?

David Silverman of the Harvard Business Review says the best cover letter he ever got went like this:

Dear David:

I am writing in response to the opening for xxxx, which I believe may report to youI can offer you seven years of experience managing communications for top-tier xxxx firms, excellent project-management skills, and a great eye for detail, all of which should make me an ideal candidate for this opening.

I have attached my résumé for your review and would welcome the chance to speak with you sometime.

Best regards,

Xxxx Xxxx

That’s fine for a position that requires a simple list of attributes. It’s like advertising something by offering a simple recitation of attributes and benefits. That’s fine for many products–basic food and clothing, taxi fares, movies in a theater, meals in a diner, and so on. When you’re selling commodities–that is, goods and services that lots of people offer–this approach works just fine.

Maybe They Want To Know More

But maybe–just maybe–you are a unique person with just the right experience, skill set, and personality for the job. If that’s the case, you probably want to reveal more about who you are.

These days, most hirers want to understand your character. They want a sense of what you would be like working in their organization. The absolute requirement is that you can do the job–that you have the necessary skills and experience.

But they also want to know: Will you be bright and creative? Will you be an engaging and challenging colleague? Will you be creative? Will you identify solutions that others miss? Will you lead and follow well, depending on the circumstances?

They want to see you. They want to visualize what you will be like in the office, in meetings, working in teams, representing the organization outside the office. They want a sense of how you handle problems. Therefore, let me suggest another brief but more intimate strategy for writing a cover letter.

A More Revealing Cover Letter

You can write a cover letter that fits on one page and grabs the hirer. It’s a simple formula. Let’s get right to it.

• Opening salutation

If you are writing to a specific person, say “Dear Mr. Gates” or “Dear Ms. Jones,” or “Dear Dr. Zhivago.” Don’t use first names. Show that you respect them, first and foremost, as professionals.

If you don’t have a specific name, use a general title, like this: “Hiring Manager.” Since this is a business letter, use a colon rather than a comma.

Whatever you do, don’t say “Hi” or “Hey.”

• Introduction

Referencing the resume, indicate how you could help the employer. Focus on the hirer’s needs and how you will fulfill those needs. Indicate something about your spirit as well.

Do one–just one–of the following:

• Reveal one aspect of your biography: Say something about your background–something unique about your story that might matter to the hirer. You can do this in a phrase.

“Growing up in Silicon Valley, building computers and participating in coding competitions, I knew I wanted a career in tech. At the same time, I have been passionate about the environment–and became a computer science/environmental studies double major at Euphoria State. So when I saw your position for a GIS expert or a major parks project, I knew I found my ideal job.”

• Reveal one aspect of your values or approach: Hint at how your values and commitments have driven you to achieve, like this:

“To manage teams, I take a three-part approach: (1) Engage the professional on my staff. (2) Set big goals with intermediate goals that advance our cause every day (3) Provide regular feedback. This approach fits the job for project manager at Acme Consulting.”

• Reveal one aspect of your results: Show how you have achieved something great, somewhere. Hint at how you can produce this kind of accomplishment to your new job.

“Since taking over as interim marketing director, Acme Widgets Inc. has increased its B2B sales by 35 percent and its B2C sales by 20 percent. Now I would like to bring my skills and experiences in web marketing to your firm’s growing marketing department.”

You might want to start the letter with your results and accomplishments. HR and other hiring agents often get hundreds of letters. Make sure they do not miss the value you would add to their team.

The goal here is to offer an enticing glimpse of your value as a team member. Don’t go into detail in the intro. Just signal that you have something real–something tangible and concrete–to offer.

Avoid all abstraction. If you cannot see it, don’t write it. Don’t say you’re a problem solver; indicate a knotty problem you solved. Don’t claim to be a great bargainer; describe a bargain you struck. Don’t say you care about equity or grassroots participation; show yourself doing something to get people involved to get a fair shake.

Be specific. Provide a vivid image. Make it physical. Put yourself and your potential colleagues in the same picture. Like this:

“At Acme Widgets, we convened the Monday Club at 10 a.m. It was an all-hands-on-deck opportunity to share our work and plans for the week. It was a way to prime ourselves to connect last week’s work with this week’s vision.. Looking back, we realize that most of our breakthroughs came on Tuesday and Wednesday–and we spent Thursday and Friday honing them and thinking about next steps.”

I would want to have that player on my team. How about you?

• Your achievements/results

Now you can go into some depth on results you have achieved. Here’s where you can get narrative.

Set the stage by stating a specific time and place. Describe the problem. Then show how you made things better. Describe the specific actions you took. Describe a barrier (a deadline, resistance, a lack of resources, whatever). Then show how it all turned out.

Try something like this:

“In the summer of 2017, I coordinated a community planning process at Bronx River Park that led to the adoption of a new master plan. Working with 12 community groups, I planned cleanups, evening concerts, and fundraisers. In three months, we got on the Bronx borough president’s agenda and got media attention to the area.”

Once you have given your narrative–again, with as many visuals as possible–you can connect this experience with the job you seek:

“I hope to bring this hands-on organizing work to your agency’s environmental advocacy work.”

That’s all. paint a picture, then make the picture relevant.

• Go deeper?

This is optional. If you have shown how you achieve results, you will get the hirer’s attention. But you may want to go deeper.

If so, isolate one quality that will bring great value to the company. Provide more fine-grained detail to show yourself at work, providing value for the organization. Something like this:

“This kind of grassroots work, I think, has the potential to give greater credibility to the organizations work. When people feel part of a process, they are willing to speak up at community meetings and in local media. They also get friends and neighbors involved. It’s a win-win. We get their energy and support; they get connections to friends and neighbors.”

Show how that work led to a great result for the company. maybe close with a quick statement of value.

• Conclusion

Restate your interest, this time with something specific about how you see yourself contributing to the company. Convey your enthusiasm. Make them what to get to know you. Be friends, without being presumptuous. Like this:

“Again, I am eager to explore ways I can help your organization. I hope we have a chance to talk soon. Thanks for your consideration.”

That’s all it takes. No groveling or posturing. Just a simple statement of respect and interest.

• Closing salutation

Be warm but professional. “Best regards” and “Sincerely” work. Avoid the overly stiff (“Sincerely”–too boilerplate) or overly familiar (“All my best”–ugh; they don’t even know you). Keep it simple. Then type and sign your name.

Other Considerations

• Too Much or Not Enough?

The template above might seem overwhelming. You want to keep your letter as short as possible. So do this: Do everything above and the edit, edit, edit. Look for ways to sharpen your main point. But don’t go short just for the sake of going short. If everything you say has value, keep it. Cut the fluff but keep the revealing information.

Consider hiring an experienced writer and editor to go over drafts. Overall, you can probably hire someone for an hour to work through all phases of writing your letter.

• Know their World

In an informal way, show that you know and appreciate the employer’s work. Say something specific about their organization, its reputation, its uniqueness, etc. Speak as a colleague. Like this:

“Having followed the park planning process in Queens in recent years, I know you have been a key player in raising funds and getting local experts (like architects, environmentalists, and educators) involved in the community. Your volunteer work after Superstorm Sandy was especially impressive. So I would be honored to join your team.”

Show you are one of them, with your values and insight.

• Keep It Active, Simple, and Direct

Keep your sentences short and direct. Use active verbs. Avoid tangents.

Good writing often requires longer sentences. I call them “hinge sentences,” because they connect and relate different ideas with hinge words (like for, and, nor, but, or, yet, and so). You can use one or two of these longer sentences–if they absolutely do a better job at explaining and visualizing ideas better than short sentences. But as a rule, keep it short.

• Be Confident, Not Cocky

Some applicants get hesitant because they don’t think they have enough experience. They will make try to explain why their inexperience might be overlooked. They’ll say something like: “While I have only been working on GIS for a year, I have developed a strong working knowledge…”

Don’t do that. Don’t emphasize your limitations. Instead, emphasize the abilities that you do offer. Say something like this: “In my GIS work, I have analyzed the causes behind gentrification in big cities, identified possible sites for new housing construction, and analyzed the changing ecologies of coastal areas since 1980.”

The reader of that passage now has a way of imagining how you’ll fit in. If you can do these tasks, you can also do other tasks.

• The Question of Informality

We live in the age of informality. Students wear PJs to class. Adults wear baseball hats to the office. People style their hair like anime characters and decorate their flesh with tattoos. Professionals open letters with “Hey.”

I’m not going to pass judgment on this informality. But hirers will.

A hirer generally wants to see you at your best. They want to know that having you on staff will not require getting a babysitter. They want to know you’ll get dressed like a professional, show up on time, work hard on company time, avoid childish distractions, listen intently in conversations, and think before you speak.

The cover letter offers a hint–a minor hint, but the only evidence at first–about your overall seriousness and maturity.

So speak clearly and simply. Be direct. Don’t try to be clever. Don’t use “bro” lingo. Whatever you do, don’t be a smart ass. Don’t crack jokes, as if you’re old fraternity brothers at a reunion. Don’t gossip or make cracks about people. Don’t be self-deprecating.

Be a pro. Speak with simple assurance and professionalism.

• Make Mass Applications?

Don’t cut and paste your prose from an application for another job. Write each cover letter fresh. If you want someone to pay you the big bucks–and give you a desk and a computer–give them the courtesy of your complete attention when writing your cover letter.

One hiring manager complained: “Nothing gets a cover letter tossed in my trash faster than seeing another publication’s name in the ‘to’ field.” Oops.

Proofing Your Letter

Don’t make grammatical mistakes or misspell words. Nothing says sloppiness more than avoidable mistakes. Fairly or not, the hirer will assume you’re as careless in your job as you are with your cover letter. Even if you’re seeking a job as a firefighter or engineer or cook, the hirer gets a bad vibe with dumb writing mistakes. It’s even worse if you’re seeking a desk job that requires attention to detail–as a graphic designer, say, or a coder.

Again, consider hiring an experienced writer and editor for an hour to do this for you. Get them to read the first draft. After you make revisions, get them to read the final draft.

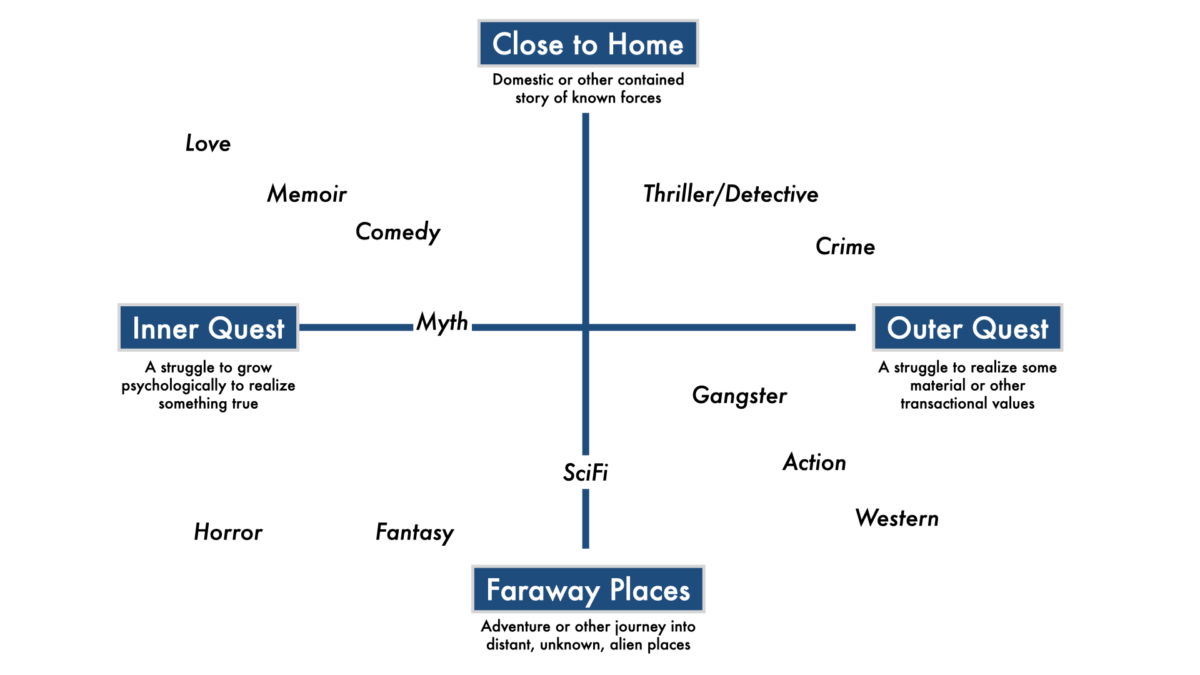

Stories are collections of hundreds of moments. In the best stories, every moment plays a critical role everything that happens, both before and after. By studying specific story moments, we can understand the whole arc of actions that make a story feel inevitable, satisfying, and complete.

Stories are collections of hundreds of moments. In the best stories, every moment plays a critical role everything that happens, both before and after. By studying specific story moments, we can understand the whole arc of actions that make a story feel inevitable, satisfying, and complete.

One example: Too many reporters fail to use the denominator when describing simple statistics. As

One example: Too many reporters fail to use the denominator when describing simple statistics. As

“Why, your calling card, of course. And if it doesn’t look just right, you’ve got to have a new one printed.”

“Why, your calling card, of course. And if it doesn’t look just right, you’ve got to have a new one printed.”

So far, so good.

So far, so good.