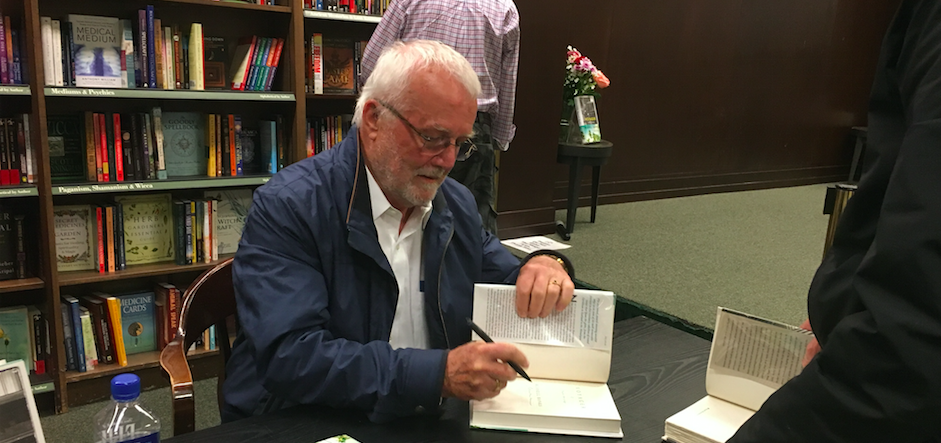

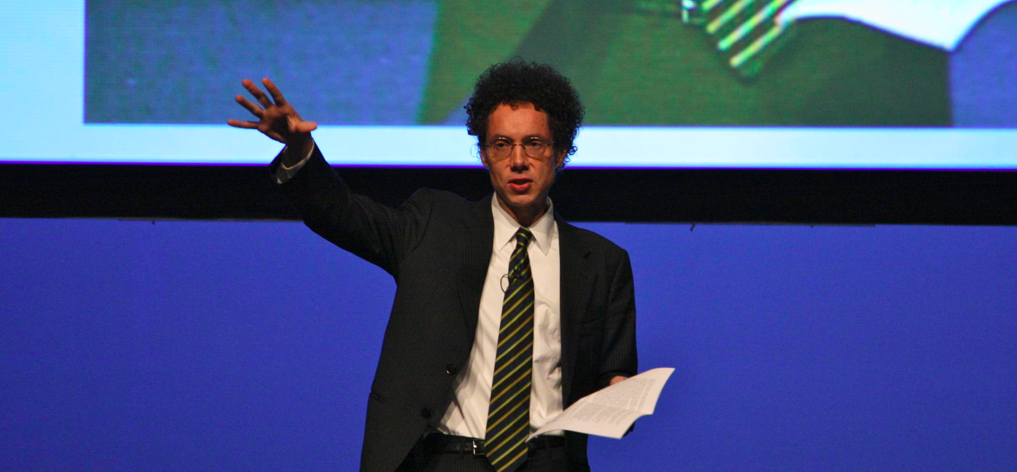

A rejection letter to Malcolm Gladwell for a draft of “David and Goliath.” We are publishing the letter because the author suggested some “writing hacks” that would have made the book better.

Dear Mr. Gladwell,

Dear Mr. Gladwell,

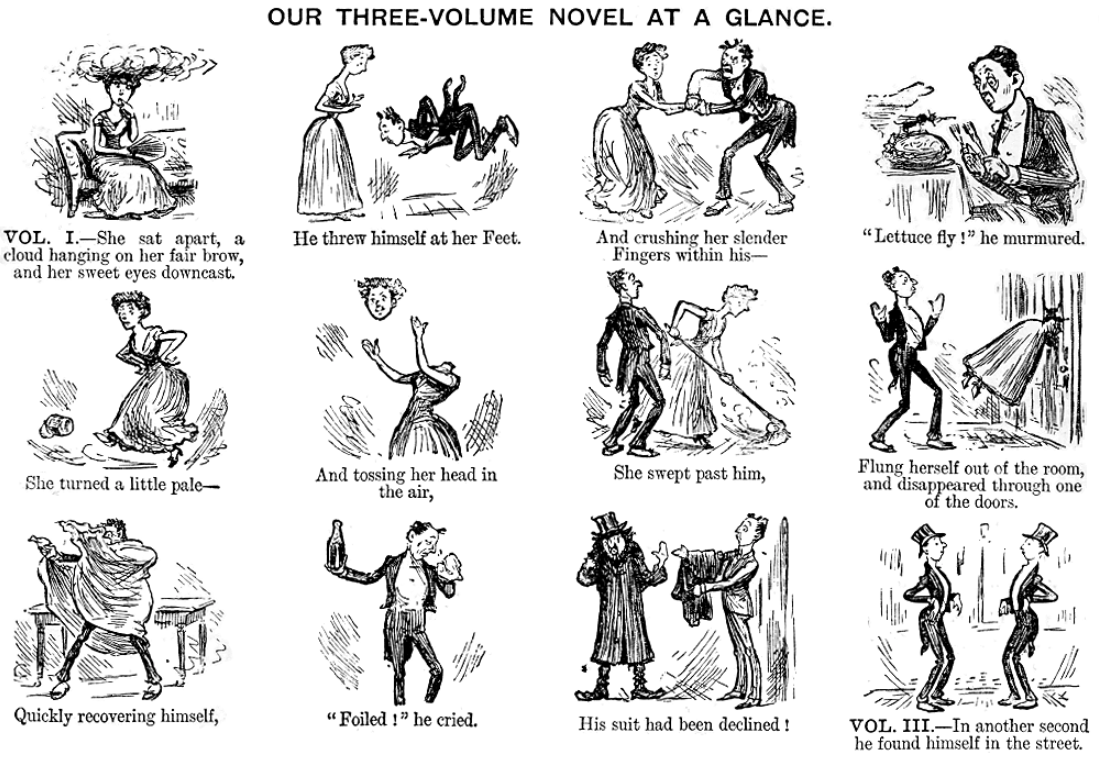

We were pleased to get the manuscript of David and Goliath for consideration at [name of publisher redacted]. We know of your success with previous pop-scholarship books. The title suggests a powerful “high concept” book. And we love—lovelovelove—high-concept books like Salt and Cod and A History of the World in Five Glasses and, yes, The Tipping Point and Blink and Outliers. When you see the title, you instantly get the premise. So we loved your title and what it promised.

We’re going to have to pass on the manuscript, though. I’d like you to rethink the concept and do more research. Right now, the book is a loose collection of anecdotes, which take huge leaps of logic, offer scanty evidence, and contain contradictions that undermine your case.

We’re going to have to pass on the manuscript, though. I’d like you to rethink the concept and do more research. Right now, the book is a loose collection of anecdotes, which take huge leaps of logic, offer scanty evidence, and contain contradictions that undermine your case.

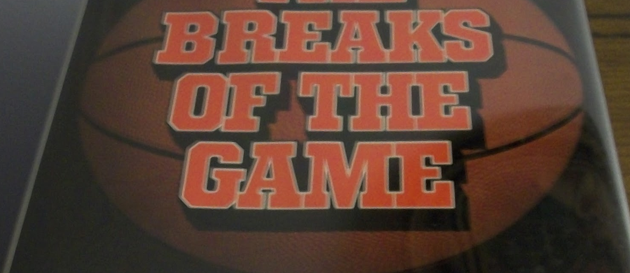

The biggest problem, though, is that the book doesn’t really take on the David and Goliath phenomenon. Sure, some sections talk about the ability of the little guy to defeat the big guy (my favorite story is about the girls basketball team that triumphs with aggressive full-court play). But more often, your discussion ranges far from that theme. Your themes include, in no particular order: the importance of “multiple intelligences,” the power of grit and willpower, the effect of peers on behavior, the dynamics of civil disobedience, the power of buzz, the strength of love, the potential of detailed research to yield new insight, and the psychological need for belonging. I’ll get to all that in a minute.

I want to publish your book—what editor doesn’t want to acquire a best-selling author?—but I simply cannot find a theme in this pudding.

Theme

Rather than just saying “there’s no there there,” let me explain what I mean. If you were to conduct more rigorous research and recast the work, you might consider a number of frameworks. Consider, for example:

The Master-Slave Dialectic: This is a key insight in Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit, probably due for a popularization. (If you don’t do it, Alain de Botton will!) The idea is simple: Even powerful people need recognition from the peons below them. When peons refuse to acknowledge the legitimacy of their superiors, those peons gain surprising leverage. This is close to the David-and-Goliath theme, but still different. Hegel’s dialectic shows the complexity of the psychological give-and-take in human affairs, rather than a simple confrontation of powerful and weak. A couple of your stories fit this theme:

Andre Trocme is a minister in a Vichy-occupied village in France. When the Nazis demand recognition of their rule, should he accede or fight? Or is there a third way—strategic defiance and withdrawal?

Wyatt Walker, Martin Luther King’s assistant, is eager to find a way to break the back of segregation in Birmingham. How do you change the dynamic of the civil rights movements when King has suffered defeats and most of white America is indifferent? Do you create a spectacle—or is it more complicated than that?

Achieving Mastery in a Messy and Indifferent World: Sounds like a how-to book, I know, but you could get away with it. This might be your best bet, if you want to keep most of your anecdotes. Everyone in your manuscript has to confront more difficult situations than they might choose. The world is messy, complex, and quite frankly indifferent to any person’s fate. (There’s an idea for a title: Man’s Fate. Andre Malraux might not approve, but he’s dead.) Think of the subjects of your work:

Vivek Ranadive wants to coach his daughter’s basketball team to play well. But his players are small, weak, and inexperienced. Stronger teams won’t give his girls a break. Or will they, unwittingly? How can he exploit opponents’ lack of imagination?

Caroline Sacks discovers that science courses at Brown are hard—and her classmates are competitive and not eager to share. Should she give up? Buckle down? Get out of Dodge?

Teresa DeBrito is a principal of a middle school where enrollment has declined drastically, taking away some of the buzz of the class routines. What can she do to engage distracted teenagers in the classroom?

Finding Voice in a Noisy World: To deal with huge challenges, people need to ignore the babel of voices around them. They need to hear their inner voice and find their truest values. When you know what really matters, everything else is easier to bear.

Wilma Derkson loses her daughter to an awful murder. Should she lash out with anger—or find a way to deepen her considerable love and humanity and to build a better world?

Rosemary Lawlor is a Catholic mother and housewife in Northern Ireland during the Troubles. The British police run roughshod over Catholics. What can change the dynamics of this war-torn isle?

David Boies is dyslexic and struggles to read. Should he work construction or find a job that challenges him more intellectually? Since he’s a lousy reader, how can learn and communicate?

Beating the Odds: What happens when you live in a world of rigid standards and practices? How can you persevere in the face of widespread disapproval—and make gambles that might pay off for years, if ever?

Jay Freireich wants to find new ways to treat children with leukemia. But other doctors and researchers are dubious—and even say Freireich’s aggressive treatment is inhumane. How can he find a way to give his “cocktail” of medications—and relentless chemotherapy—a chance?

Maybe these themes lack the same sex appeal of David and Goliath, which is, after all, one of the great parables of western civilization. But they deal, more coherently, with the stories you tell.

Maybe you can’t use all the stories you offer in this manuscript. That’s OK. The best works of literature come not just what’s in them but also what’s not in them. Anyway, you simply need to work hard—adding and subtracting and shaping—till you get the theme that truly unifies your work without simplifying too much.

If you want to keep all your pieces, don’t present them as a unified argument. Just say: Musings of a Pop Journalist, or some such.

Research and evidence

“When you can’t create,” Henry Miller once said, “you can work.”

David and Goliath feels like a mish-mash. Maybe you focus so much on creating a neat theory that you didn’t do the necessary work to test and prove that theory.

Sometimes, the separate pieces read like first drafts of magazine or newspaper articles. You often rely on one or two books or articles, it seems, when you could do a lot more research—doing library research, digging into archives, and interviewing participants. I noticed that your weakest passages—like your strange attack on the Hotchkiss School—did not appear in The New Yorker. I’m not surprised. No way David [Remnick, the editor] would allow that in his magazine.

Which reminds me. You once said something at a conference that concerns me.

I attended a Nieman conference on narrative journalism back in 2003, when you were the keynote speaker. You said you need to spend only a day or two with a subject to understand what makes him or her tick. Your point, I think, was that your profiles focus more on ideas than personalities. You care about Lois Weisberg because of the idea she represents—that “weak ties” bind communities better than strong ties—and not because of her life story. Fair enough.

Now, I know you conduct more than one interview with some of your subjects. But David and Goliath takes a one-and-done approach too often. In fact, your section on Wyatt Walker shows no real first-hand understanding of the subject. You could have interviewed dozens of the Birmingham movement’s activists, including Walker himself, but instead you relied mostly on Diane McWhorter’s book Carry Me Home. As a result, your account is thin and misleading. I wish you had read The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement, by Aldon Morris, which offers a better idea of how the Birmingham campaign succeeded.

Let’s get specific. True, as you say, Americans were shocked by the photograph of dogs attacking a slight black boy near a demonstration. True, most people don’t realize that the dog’s victim was not a protester but a bystander. True, Walker was pleased by the ugly display of police brutality, since it revealed the fundamental violence of segregation.

But the Birmingham campaign was much more than a photo op. Fundamentally, Project C was a “withdrawal of consent” from the segregationist regime. No regime, King understood, lasts long when people reject its legitimacy. In the campaign’s many phases—the sit-ins, boycotts, marches, jailings, and eventually the occupation of downtown—activists refused to play by segregationist rules. Yes, the photo was dramatic. But without everything else, it would have revealed little more than one nasty man’s meanness and temper. Oh, yes: Why no word about King’s iconic “Letter From Birmingham Jail”?

I also wonder about your account of the Impressionists. You depict them as renegades who snubbed the Salon in order to display their work in their own shows. But that’s not quite right. They pursued the Salon, again and again. And when Manet got in, his work created a buzz. Granted it was a negative buzz—but people were talking. Later, when the Impressionists held their own show, they benefitted from the advance PR.

And why the animus toward the Hotchkiss School? You argue—with no evidence whatsoever—that its small classes “so plainly make its students worse off.” Huh? Parents send kids there, you say, because they “fell into the trap” of assuming that “the kinds of things that wealth can buy translate into real-world advantages.” Seduced by Hotchkiss’ gorgeous campus and amenities, you say, parents spend big bucks and get those awful small classes. Malcolm, get a grip. Have you ever taught a class? I don’t mean standing in the front of a vast auditorium, but working closely with people, on their terms? Do you know what happens when students gather around a Harkness Table? Think back to your days at the University of Toronto. Do you remember seminar classes, with a dozen students? Those seminars can be amazing. Where is your evidence that small classroom conversations fail? You don’t have any because it doesn’t exist.

You say bigger classes produce greater diversity. But large numbers don’t always produce diverse, open-minded discussion. A class of 20 or 30 often explores fewer ideas than a class of 12. It depends on how engaged the students are, how challenging the culture. If you think diverse expression comes from students with different life experiences, consider that Hotchkiss students come from 28 countries and most of the states of the U.S. Yes, it’s elite—and rich. But Hotchkiss also offers generous scholarships. Some 37 percent of all students receive financial aid, with an average grant of $32,500.

One more thing. Why sneer at the Steinway pianos at Hotchkiss? If you had written about Hotchkiss in Outliers, you would have extolled the virtues of making instruments available to young musicians. You celebrated Bill Gates’s unusual access to computers in high school; why not celebrate the future maestro’s access to great instruments? After all, don’t musicians need 10,000 hours of practice too?

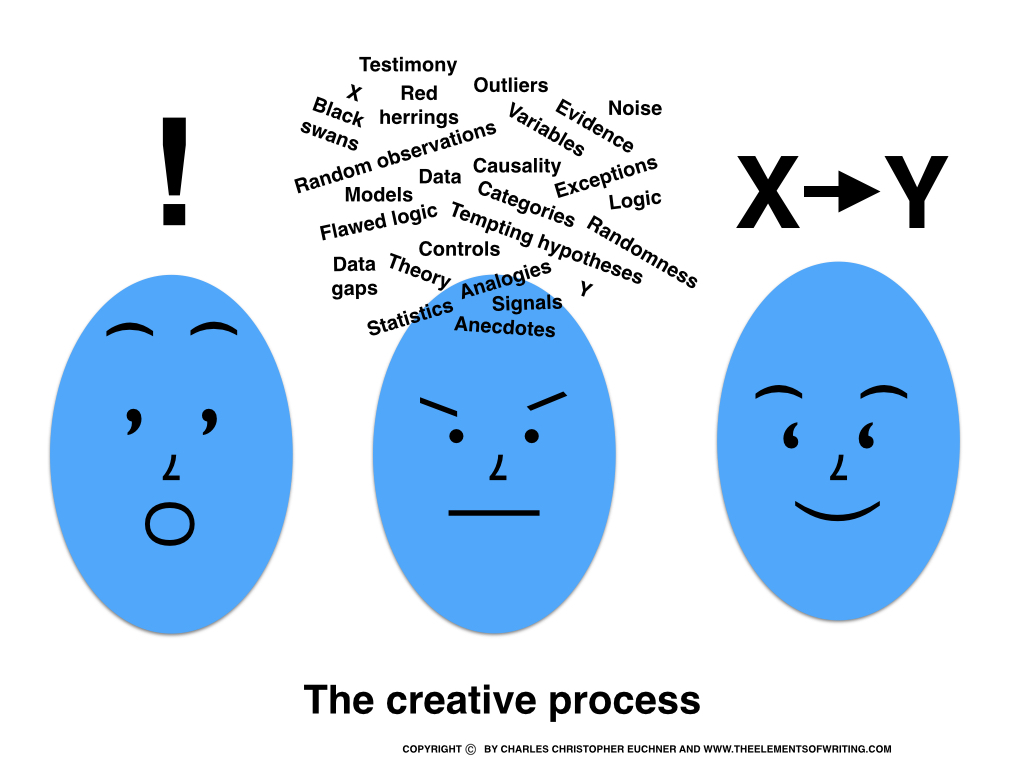

The Logic

Your logic regularly misses the mark. You often state (or imply) that X causes Y when you see X and Y together. But of course, the world is never so simple. Lots of variables swirl around all the X’s and Y’s of all stories. You need to define the variables—and then use consistent definitions. Then you need to “isolate the variables” to show which ones exert more force than others.

Take the story of Caroline Sachs. You argue that she made a mistake in choosing Brown over Maryland because she struggled with core science courses at Brown. Why not star at a lesser school, you say, instead of struggling at a great school? Why not, in your terms, be a big fish in a small pond rather than a small fish in a big pond? Your charts show that students in the top decile of a number of schools – public and private – publish more papers and win more honors than students lower in the class rankings. Let’s put aside your own incredulity at the fact that non-Ivies do good work. Your point is that middling achievement at Brown “made her feel stupid,” damaged her self-esteem, killed her love of science.

Maybe, but I’m not persuaded. Let’s start with definitions. True, Brown is a more elite school, but that hardly makes it a bigger pond. Strictly by the numbers, Maryland is more than four times bigger than Brown (26,000 to 6,000 students). I know you mean Brown has a “bigger” status, but this can be confusing.

I asked the science coordinator at Maryland for his perspective. He started with the numbers:

“Maryland is a much bigger pond than Brown. We have more than 5,000 natural sciences/computer science/math majors and 3,800 engineering majors. Brown University’s total enrollment in all disciplines is 6,100. [Note: Brown graduates about 600 science students a year.] Therefore we have many more STEM fish than Brown has undergraduates.

“We also have many big fish, earning distinctions like Goldwater Scholarships, other national fellowships, etc. Such outcomes are not the province of the Ivies alone. In fact, publicly available data on Goldwater Scholarship Winners over the last 5 years – University of Maryland 14, Brown University 3. Even if you compensate for total undergraduate enrollment (our undergrad student body is four times that of Brown), we are still ahead. And both schools only get 4 nominations each year.”

OK, maybe you didn’t mean big and small pond in such a literal way. You were referring to Brown’s “big pond” status and Maryland’s “small pond” status, right? But that’s not quite fair either. Sure, Ivy admissions are absurdly competitive, state universities less so. But does that mean their STEM classes require less work? Not necessarily. Back to the University of Maryland official:

“A student who struggles with early science classes at Brown will also struggle with early science classes at Maryland. In fact, it may initially be even more difficult for such a student at a flagship university, as introductory classes tend to be larger, and students who are struggling may not stand out as much. However, I suspect Brown’s introductory courses are fairly large as well.

“However, she may find herself among more female science and engineering majors than she would see at Brown, and this might encourage her persistence and success!”

By your own account, Caroline took too on many classes and extracurricular activities in her freshman year. And she did get a B-minus in the critical chemistry class. Who says struggling with a difficult subject should drive her away? If she were a true David, why shouldn’t she face those tough challenges? Won’t that sharpen her resolve?

Since you like anecdotes, let me tell you one. When I was a student at Vanderbilt I had a friend named Tom who desperately wanted to be a doctor. But he struggled, semester after semester. So he started taking liberal arts courses and enjoyed himself for the first time. But he still had the science bug. So after Vanderbilt, he took pre-med classes at Millsaps College. He excelled, went to med school, and eventually did a residency at Vanderbilt. You might say he made it by going to a small pond. But he excelled in both the big and small ponds. Years later, he looked back with happiness that he had learned how to struggle. He felt “stupid” sometimes, sure. But he persevered, looked for different routes to his goal. He didn’t succeed right away. But he found his own path. Maybe that approach would work for Caroline too.

If Caroline really loves science—really loves science—don’t you think she’ll find her place? Maybe Maryland would have been a better choice, maybe not. But she doesn’t need to take a straight line to her goal. In fact, a meandering route, with some wrecks along the way, might make her a more complete human being.

Doesn’t a college education mean more than grades and job prospects? In one of your most moving sections, you describe the courage of Andre Trocme against the Nazis. Why did he settle in this remote village in the first place? Not because of his job prospects, but because his pacifism isolated him from the French Protestant Church. If he had cared about conventional success, he wouldn’t have taken this route. But he wanted to live a decent life.

Won’t Caroline live a good life if she pursues what she loves, regardless of where she finishes in her class and what accolades she receives? If she’s smart, hard-working, and open-minded, she’ll find her sweet spot. It’s when we try to game the system that we lose out on what matters.

For such a contrarian, you seem to accept some tired old ideas about how education works. In a Gladwell school, teachers stand in the front of the room and tell their kids what they need to learn, then solicit responses from the kids. You quote, approvingly, a teacher fretting about students “talking about something that has nothing to do with what they’re supposed to be working on.” Ah, so everyone in your big classes should all focus on the teacher in the front of the room. In a Gladwell school, success is measured by tests and awards, rather than the joint exploration of ideas. This is a sad, impoverished ideal of education, Malcolm. I suggest you put Ken Robinson’s The Element on your reading list.

You take logical leaps all over the book. Consider the story of Jay Freireich, the doctor who fought to provide more aggressive treatment for leukemia. But your explanation—that his unhappy childhood gave him the determination to fight the good fight— is facile at best. All our joys and sorrows make us who we are. But without some kind of inspiration—which he got from his family physician and high school physics teacher—his rough childhood might have broken him. So maybe it was the nurturers who gave Freireich his fire, not the tragedies of his childhood. It’s hard to say. Lots of people with rough childhoods fail to persevere; lots of people with happy childhoods do persevere.

So here’s another logical problem. You depict Freireich as an SOB, a tyrant with “no patience, no gentleness.” In fact, one colleague remembers him as “a giant, in the back of the room, yelling and screaming.” You call him a David. But is he? Freireich started out a David, for sure. But after he was inspired by others and enrolled at a great state university, he turned into a Goliath. Thank goodness. It took a Goliath to fight the hospital’s approach to leukemia treatment. But that doesn’t fit your neat interpretation.

Let’s look at one more definitional problem. In your account of the Nazi’s bombings of London, you note that Winston Churchill and others feared mass panic. But instead, London responded with bravado. Why? The psychologist J.T. MacCurdy argues that those who survive such attacks fall into two groups: the “near misses” and the “remote misses.” The near misses, MacCurdy says, “feel the blast, they see the destruction,” and experience trauma. The remote misses don’t experience the horror first hand, avoid the trauma, and respond with a strange sense of invincibility. Fair enough. Experiencing something awful affects people more than hearing about it.

Then you apply this typology to the experience of Fred Shuttlesworth, Martin Luther King’s associate who fought for civil rights in Birmingham. You describe the awful day when Klansmen bombed his home. The force of the blast blew windows a mile away. Shuttlesworth was calm. “The Lord has protected me,” he said. “I am not injured.” Malcolm, you call this “a classic remote miss” because he wasn’t maimed or badly injured. But he was there, Malcolm—right in the middle of the bombed-out house.

Maybe Shuttlesworth maintained his equanimity because he had already endured so much violence and hatred and survived it? Shuttlesworth and other civil rights heroes knew they faced mortal danger every day. They faced that danger squarely because the cause was too great not to do so.

Maybe something else was involved. Maybe Shuttlesworth found comfort in his faith and in the love of his family and friends? Maybe that faith—a belief in God’s undying love and mercy—sustained him. Consider also Dr. King. How did he maintain his serenity and humor when a woman stabbed and nearly killed him at a book signing? How did Pope John Paul maintain his spirit when he was shot at St. Peter’s Square? I would submit that their faith gave them a heart that helped them overcome the tragedies of life.

Style

Now for a few quibbles about style …

I love simple writing. When exploring complex ideas, breaking points down into small pieces makes sense. When a complex term comes along—an idea from scholarly research, for example—it makes sense to define it slowly. Let the reader absorb each piece fully. Let the reader build knowledge, block by block.

This, I must say, you do well. You never—ever—get stuck in the quicksand of arcane, abstract, complex verbiage. I remember when I read your explanation of the “strength of weak ties,” an idea that a sociologist named Mark Granovetter developed. I was thrilled because you took this obscure but important concept and you made it simple and compelling for a broad audience. You deserve credit for encouraging journalists of all kinds to explain complex ideas well.

Now, though, you sometimes write like a kindergarten teacher. Your leading questions are cloying. Your use of italics to emphasize points already made well is insulting. Your use of “we”—as in, “Giants are not what we think they are,” “We think of underdog victories as improbable events,” “We think of things as helpful that actually aren’t”—not only grates but sets up straw men. Language matters.

With these approaches, I think you mean well. So I was even more annoyed with your snide comments. In describing a Harvard student’s move away from the sciences, you say: “Harvard cost the world a physicist and gave the world another lawyer.” I have no love of lawyers, but it’s a cheap shot—and, in your own reckoning, some lawyers are decent people, like David Boies. And maybe—just maybe—the Harvard student wasn’t cut out for science. And are all lawyers really so bad? What about your hero David Boies?

It’s also hard to stomach the easy omniscience of your style. You say Jay Freirich—couldn’t remember the name of the woman who raised him “because everything from those years was so painful.” Maybe, but it sounds facile. And it’s unnecessary.

Moving Forward

So far I have outlined problems with framing your argument, making theory simplistic, using terminology imprecisely, failing to offer evidence (or ignoring contrary evidence), and creating a simplistic world with your kindergarten style.

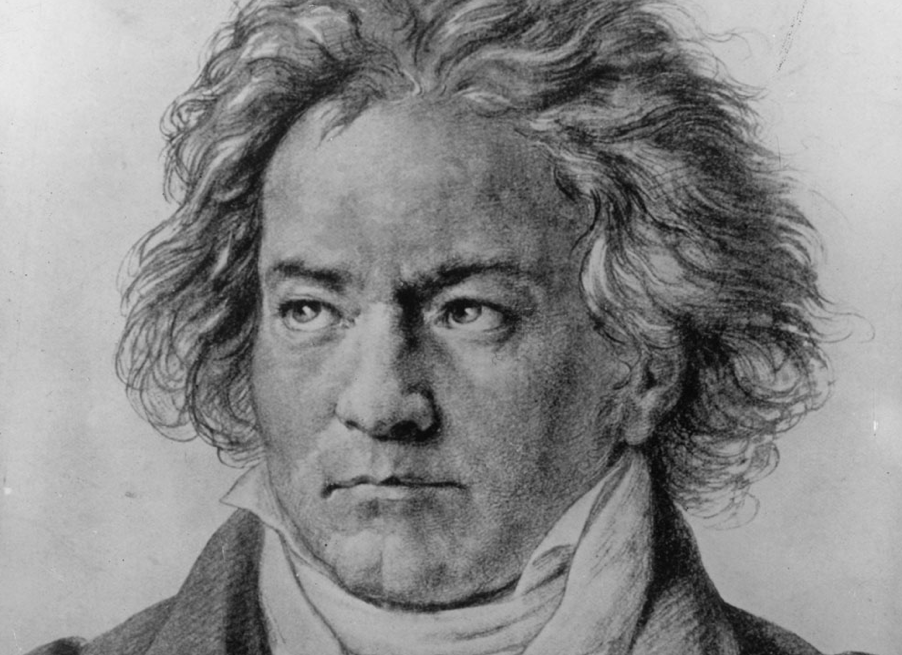

But the problem is deeper—and I can explain it best with reference to your book Blink.

Recall your enthralling account of fake kouros, a marble Greek statue said to date back to the sixth century before Christ. The Getty Museum paid millions to acquire the piece after using the latest scientific analyses to vet its authenticity. But then art historians had a visceral reaction—what one called “intuitive repulsion”—to the statue. For reasons they could not articulate right away, the statue didn’t look right. It looked too “fresh.” In concluding your discussion, you celebrate the power of the “blink” judgment. “Just as we can teach ourselves to think logically and deliberately,” you say, “we can also teach ourselves to make better snap judgments.”

In that rendering, it sounds like magic. But in Outliers, you get closer to the point: it’s all about experience. Those artists could tell the statue was fake because they were immersed, deeply, in art and archaeology. They lived and breathed the world of antiquity. They understood not just surface appearances, but the deeper essence of the thing. That—not just facile understanding of definitions and rules and patterns—is where real understanding comes from.

And that’s what you’re missing. Over the years, you have become entranced with quirky “rules,” “theories,” and “patterns” that explain complex realities of life. But you never go deep. You don’t spend significant time with your subjects. You find a great parable and match it with a fun theory. When the theory doesn’t fit the parable, you ignore the misfit. Lacking deep knowledge of any subject, you cannot respond critically. And lacking the scientist’s respect for difficult problems and disdain of simple answers, you skate forward to new parables and fun theories.

So, Malcolm, I’m afraid that we cannot accept this manuscript, as is, for publication. I realize that it would sell millions of copies. But in this age of ebooks, we publishers have a challenge. When we take on a major new work, we need to make sure it meets our highest standards. Anyone can patch together a collection of anecdotes and research notes. We need to expect more.

Please consider our ideas for sharpening the book’s focus and strengthening its research and argumentation. If you are committed to producing the best book possible, we will be too.

If you want to pass on our offer, you might consider taking the manuscript to Little, Brown. They might publish it…

The Hackmaster General of the U.S., all will agree, is Tim Ferriss.

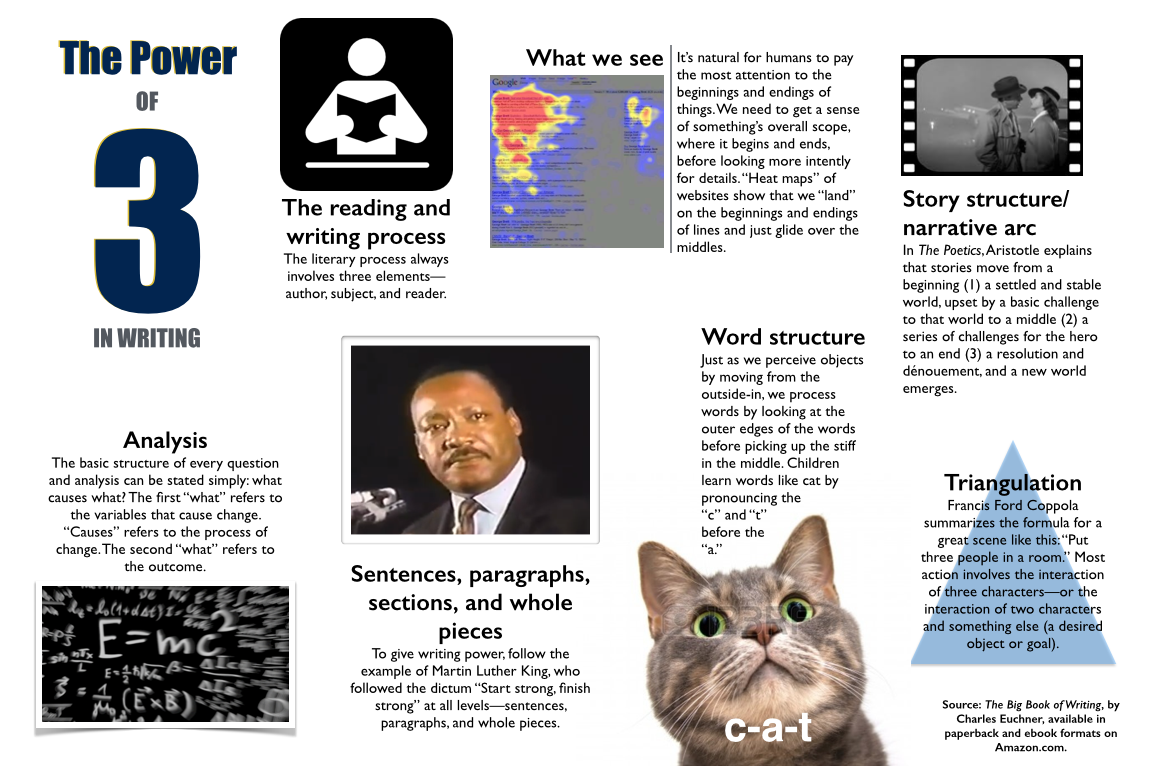

The Hackmaster General of the U.S., all will agree, is Tim Ferriss. The ideas can be grouped into ten categories: (1) Commitment, (2) Focus, (3) Planning, (4) Journaling and Note Taking, (5) Divergent Thinking, (6) Gathering Material, (7) Questions, (8) Storytelling, (9) Details and Style, and (10) Integrity.

The ideas can be grouped into ten categories: (1) Commitment, (2) Focus, (3) Planning, (4) Journaling and Note Taking, (5) Divergent Thinking, (6) Gathering Material, (7) Questions, (8) Storytelling, (9) Details and Style, and (10) Integrity.

That’s the writer’s ultimate job. The best writer is an observer. The best writer sees what others do not see. This writer pays attention, carefully and with an open mind, to what’s going on. Rather than falling into lazy habits and assumptions, the best writer looks to see what is not instantly apparent.

That’s the writer’s ultimate job. The best writer is an observer. The best writer sees what others do not see. This writer pays attention, carefully and with an open mind, to what’s going on. Rather than falling into lazy habits and assumptions, the best writer looks to see what is not instantly apparent.

Back in 2016, I was eager to get some answers from Donald Trump, the Republican nominee. As a longtime developer and TV celebrity, Trump had not been involved in any of the major issues of the day. He spoke out occasionally but never had to work through the complexities of war and peace, the economy, the budget, crime, immigration and labor, and more.

Back in 2016, I was eager to get some answers from Donald Trump, the Republican nominee. As a longtime developer and TV celebrity, Trump had not been involved in any of the major issues of the day. He spoke out occasionally but never had to work through the complexities of war and peace, the economy, the budget, crime, immigration and labor, and more.

Hyperlinks: Before the Internet, of course, the very idea of hyperlinks was just a fantasy. Who could have imagined being about to jump from what you’re reading to a completely different document or video in an instant? Maybe Alvin Toffler and a few other futurists, but the idea never occurred to me until it started happening. And, in fact, the early web used few hyperlinks. Now they’re everywhere.

Hyperlinks: Before the Internet, of course, the very idea of hyperlinks was just a fantasy. Who could have imagined being about to jump from what you’re reading to a completely different document or video in an instant? Maybe Alvin Toffler and a few other futurists, but the idea never occurred to me until it started happening. And, in fact, the early web used few hyperlinks. Now they’re everywhere.

One interviewer who has never put himself above his subjects is Brian Lamb, the founder of C-SPAN and the host of Book Notes.

One interviewer who has never put himself above his subjects is Brian Lamb, the founder of C-SPAN and the host of Book Notes.

What comes next is even more intriguing.

What comes next is even more intriguing.

We’re going to have to pass on the manuscript, though. I’d like you to rethink the concept and do more research. Right now, the book is a loose collection of anecdotes, which take huge leaps of logic, offer scanty evidence, and contain contradictions that undermine your case.

We’re going to have to pass on the manuscript, though. I’d like you to rethink the concept and do more research. Right now, the book is a loose collection of anecdotes, which take huge leaps of logic, offer scanty evidence, and contain contradictions that undermine your case.

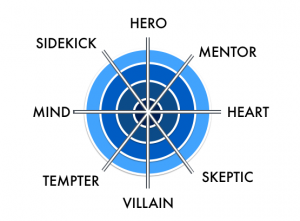

Which led me to wonder: Are we leaving anyone out?